I wish I could tell you that Atom Egoyan’s films are as interesting as David Cronenberg’s or Guy Maddin’s, but they aren’t.

Are they more realistic? Sure. His characters stammer and mumble. They speak quietly and move clumsily. They affect pained expressions instead of Maddin’s exaggerated silent movie mugging. But then again that may be the point. When life seems meaningless, or when disaster strikes, people don’t always spend an hour in makeup, shoot a few takes before the director yells “Cut!” and then break for lunch. Sometimes people just freeze or go numb.

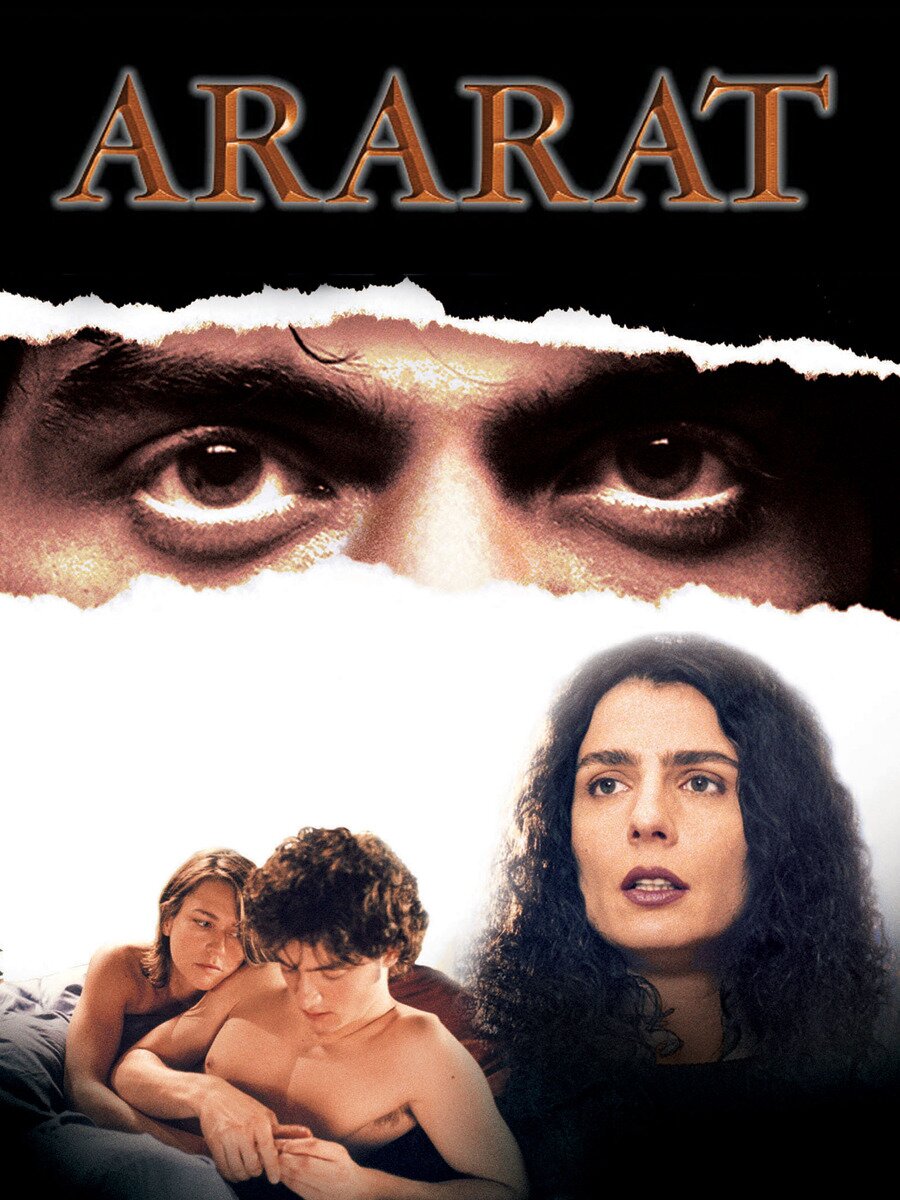

Egoyan and his wife, actress Arsinee Khanjian, know of what they speak. They are intimately familiar with grief and loss and can be justly credited with raising awareness of the Armenian genocide, which they explore in depth in Ararat. Khanjian’s character, Ani, tries to tell the story of her culture through art history presentations while her stepdaughter publicly calls her out for allegedly murdering her husband, while Turkish actor Ali tries to connect with Armenian film director Edward Saroyan, but only succeeds in alienating him. Edward, played by Charles Aznavour, is wealthy, cultured, and seemingly has it all together until Ali’s offhand comment reduces him to inarticulate babbling. “Who are these people, who can hate us so much?” he wonders aloud, bewildered, before his mask slips back into place.

As someone who’s grown up around Holocaust survivors, in a house where the walls were covered with the etchings of those who lived through the camps, I completely understand what Egoyan is going for here. And yet… someone actually had to write that line.

The Sweet Hereafter went so far as to be nominated for two Academy Awards in 1997. I still remember how the Canadian press built the film up to be a masterpiece on par with Citizen Kane – especially since it starred Canadian film darling Sarah Polley, who we’ll be covering in a later installment. The passage of time has revealed it for what it is, however: a competent study of tragedy befalling a Canadian small town when a bus crash kills several children. (Inquiries are made, and everyone decides that things would be better off if the matter were left alone. It’s basically Fargo without the murder mystery or humour.)

Then we have 2009’s Chloe, the best known and most financially successful of Egoyan’s many erotic thrillers. Rather than reveal her insecurities to her hunky prof husband, gynecologist Catherine decides to concoct an elaborate revenge fantasy – first hiring escort Chloe to try and seduce David, then seducing Chloe, then breaking things off with Chloe after learning that David never cheated on her. Meanwhile Chloe gets revenge by seducing her son, confronts Catherine and tells her she’s in love, and then is accidentally pushed out a window by Catherine/intentionally falls to her death. And then, life goes on as normal.

It sounds convoluted, and it is, but the film does hit home: often, when people cannot communicate using words, they use sex instead, and not always good sex at that – reviews of his films often mention how unsexy Egoyan’s sex scenes are, which is, again, probably the point. He is here to sift through the messy and often tedious work of processing grief and alienation, and present it with as little Hollywood razzle-dazzle as possible.

Before we move on to Paul Haggis, a filmmaker whose approach to dealing with hopelessness and trauma follows a much more conventional three-act structure, I want to leave you with a strange and tragic example of life imitating Egoyan’s art: When a murderous “incel” – of Armenian descent – acted out his sexual frustration by plowing a van into a group of passerby on a busy Toronto street last year, killing 10 and injuring 15, Egoyan flew back from Paris to participate in the mourning and was interviewed by Canadian news channel Global News. They called it a “familiar scene” for the director, who stammered about how “unimaginable” the tragedy was, how the outpouring of grief was an “expression of community”. Was he thinking of Edward in Ararat? The battered townsfolk of The Sweet Hereafter? Or the dark sexual politics of Chloe? Perhaps all three?

*****

See the previous installments in the series:

Part 1 on Heroes: ‘Scott Pilgrim Vs The World’ Vs Terrance Denby and ‘Sidequest’

Part 2 on “Humour”: The Libertarian Fantasy of ‘Letterkenny’

Part 3 on Graphic Novel Nihilism: The Harsh Truths of ‘Essex County’

Part 4 on Spawn and Wolverine: Banished From The Promised Land: A Tale of Two Canadian Anti-Heroes

Part 5 on Science Fiction Dystopias: Inside Quebec’s – and Canada’s – Replicant Culture

Part 6 on Animation: The Garrison Mentality: More Than Meets The Eye

Part 7 on Pop Music: How To Build A Successful Canadian Musical Act

Part 8 on Anne of Green Gables and The Traumatized Artist: Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Treacherous Alpine Path

Part 9 on Avoiding the Serious: Mordecai Richler, Montreal, And Gritty Realism

Part 10 on Southern Ontario Gothic: The Marriage of the Mundane and the Fantastic

Part 11 on Margaret Atwood’s Reign of Terror: Literary Tyranny and The Handmaid’s Tale

Part 12 on the First Nations Fraud: Whitewashing Genocide: Truth, Lies, and Joseph Boyden

Part 13 on the inventive Esi Edugyan: A Novel I Cannot Recommend Enough

Part 14 on Generation X Origins: Douglas Coupland And The Hopeful (?) Future Of Canadian (?) Culture

Part 15 on Jordan Peterson Rising: Canadian Culture Creators And The Intellectual Dark Web

Part 16 on The Awkward Quiet: David Cronenberg’s Silent Hell

Part 17 on The Saddest Music In The World: Guy Maddin’s Surrealist Madness

Comments

Leave a Reply