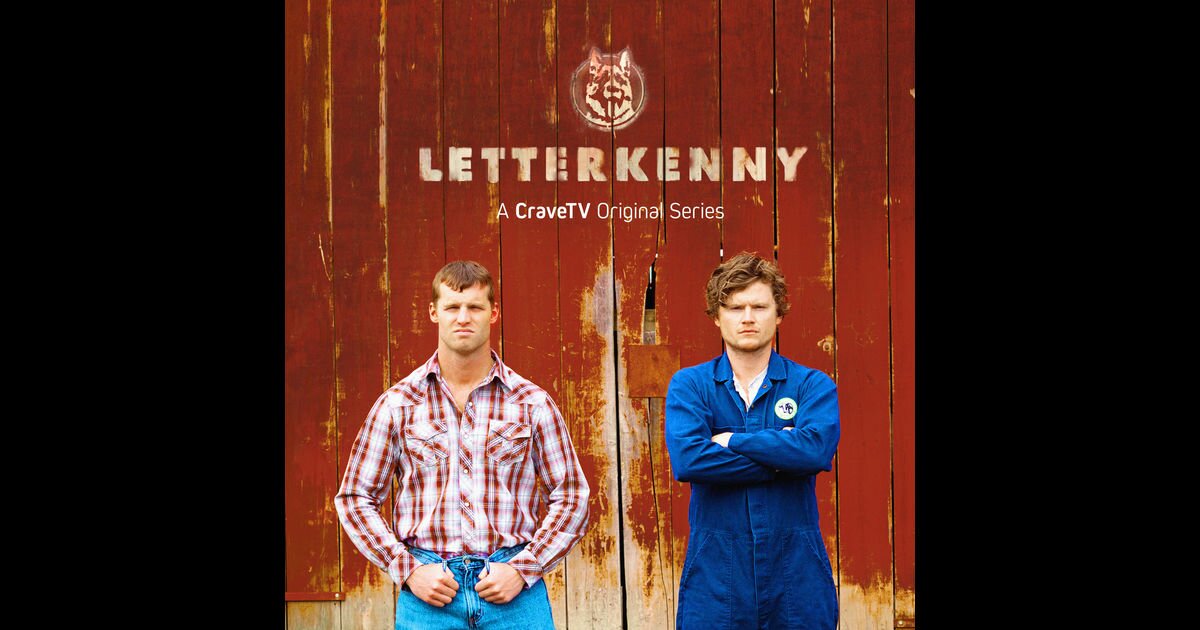

In our last post we explored the high-energy, low-stakes, and ultimately aimless retro-gaming netherworld that was Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World and found a lot of art but little matter. So for now we’ll depart the big city of Toronto and take a trip into Canada’s equivalent of flyover country into the little town of Letterkenny.

Now, I should state right up front that making fun of rustics and calling it “Canadian humour” is a trope almost as old as Canada itself, even though I do in fact know that there’s nothing uniquely Canadian about it. Letterkenny is in a tradition dating back to the grand old man of Canadian humour, the Canadian Mark Twain, Stephen Leacock (who I’ll be covering in a later installment).

But among the countless lame and derivative creative properties featuring big city fish in a small town pond that have been foisted upon us since Leacock’s heyday of World War I, Letterkenny stands out as having a heart, a brain, and a soul. Especially when it’s compared to the bloated and so-unfunny-it’s-actually-funny Schitt’s Creek, the taxpayer-funded national broadcaster’s offering in the Canadian-small-town-comedy genre.

Letterkenny’s best asset is its top-shelf writing, with characters tossing off lines like “I’ve hovered schneef off the cover of Gordon Korman’s ‘This Can’t Be Happening At MacDonald Hall!'”, which is funny even if you’ve never read Korman’s Canadian young adult novels (I have). It’s brilliantly witty despite the copious profanity, drug and toilet humour. If you thought Canadians were polite, think again. These hicks, skids, and hockey players aren’t putting on any big city airs for anybody, and what’s more, the actors and writers are actually acquainted with the world they present. They embody the realness of Hockeytown, Canada, and the equanimity with those folk greet fortune or catastrophe alike. You forget they are acting at times, and at times they probably aren’t.

The main character and toughest guy in Letterkenny, Wayne, is a squinty-eyed, perpetually frowning farmer and paragon of Canadian masculinity who’s so unmovable that he can rock black snowpants and still look utterly fearsome. Wayne may be simple, but any man who observes, “It’s a hard life pickin’ stones and pullin’ teats, but as sure as God’s got sandals, it beats fightin’ dudes with treasure trails!” is no dummy. (I’ll wait while you google “treasure trails.”)

His role is that of the mostly benevolent enforcer of the loose norms that govern Letterkenny. He and his boys, the dim Darryl and the surprisingly sensitive Squirrelly Dan will not hesitate to take their tarps (shirts) off and engage in a good donnybrook (fight) when provoked, but most of the time they don’t need to. There are no real villains in Letterkenny, just a couple of unruly hockey players involved in a completely consensual polyamorous relationship with Wayne’s sister Katy, a group of Canadian Natives with a completely justified grievance over money they’re owed, and a small band of scheming, pretentious skids who are too busy organizing raves and doing small-time drug deals to get up to much else beyond small-time cons.

The Thoreau-loving libertarian would, I think, find a lot to appreciate in Letterkenny. There are no corrupt cops, no moralizing preachers (Pastor Glen, the sole representative of organized religion, carries an obvious torch for Wayne), and everyone conducts themselves as though they just stepped out of the Garden of Eden, indulging in all sorts of carnal passions and illegal substances but remaining thoroughly kind and innocent throughout. Wayne beats up a man who gets out of line, but invites him to Darryl’s Super Soft Birthday Party later on. Rather than keep an inheritance for themselves, Wayne and Katy allow the other residents of the town to make the case for why they need it more. Even the dopey hockey players get better at their craft and learn to stand on their own two feet after Katy breaks it off with both of them.

The closest thing you could compare the show to in American popular culture would be the Blue Collar Comedy Tour, though the world of Letterkenny can’t be captured by marketing-friendly slogans like “Git ‘Er Done!”, “You Might Be A Redneck If….” or “Here’s Your Sign!” The show is deceptively complex and deliberately understated, without a single wasted word or gesture. Wayne and Darryl’s silent shunning of Squirrelly Dan when he describes his new girlfriend’s bedroom proclivities is a subtle commentary on masculinity, while the hicks’ quiet recognition of the similarities between themselves and their French-speaking doppelgangers on the Quebec border does much to promote national unity.

Possibly the show’s best aspect is the nuanced way in which the blossoming relationship between Wayne and Native gang leader Tanis is handled. Though Tanis and her crew’s violent ways initially results in her being banned from Letterkenny, she and Wayne find common ground in being equally tough. In a country where attempts at reconciliation between the two groups often goes disastrously wrong, Tanis and Wayne feel like a natural couple, and though they don’t last you do want to see them back together.

Not only isn’t this the broad comedy of the Blue Collars, this humour is definitely not a product of the hardscrabble world of American grit and guile winning out over an overreaching state or big corporations. Without meaning to, the show reveals a bit of Canadian narcissism, and a whiff of smugness- that life’s been mostly figured out here in Letterkenny, and if those city folk and culture warriors would just let go of their priggish morals and let things take their natural course they would see that too. Like Scott Pilgrim, Wayne and his crew are holding all the cards from the first moment, and most of the comedy comes from the attempts of bumbling “degens” from upcountry or clownish alt-righters played by Jewish actors and their laughable attempts to upset the balance, and the constant stream of good-natured insults and insights.

As you get into the later seasons, you can still marvel at the dialogue and quote it during real life hockey games, but the affected courtesy (“How’re you now?” “Good’n’you?”) starts to wear after a time, which is probably why the episodes are kept short, and the seasons never last more than six episodes.

We’ll be ditching the humour for a few posts, but we’re not quite ready to depart this rural wonderland quite yet. Next time, we’ll get deadly serious about the lack of a moral centre on the Canadian back-country when we explore Jeff Lemire’s haunting graphic novel, Essex County.

****

Part 1 on Heroes: ‘Scott Pilgrim Vs The World’ Vs Terrance Denby and Sidequest

Comments

Leave a Reply