What do you do when confronted with the absurdity and meaninglessness of life? Peterson tries to make sense of things with Maps of Meaning and Rules for Life. Cronenberg chooses to exaggerate way, way past the most horrific boundaries imaginable. But Guy Maddin takes a different approach and leaps out the escape hatch into insanity.

Maddin can best be described as a hybrid of Dostoyevsky, Dali, Freud and Chaplin. He is the dark side of Findley and Davies, with their conventional narratives, their organized and rather dry Jungian taxonomy of archetypes. But then again Findley and Davies were representatives of Southern Ontario Gothic, where even the supernatural is peaceful and orderly. Maddin is from Winnipeg, Manitoba, a place buried by -40 C cold, hemmed in between rivers and lakes, split by railways going out in every direction, and the site of the General Strike of 1919, where 30,000 working men and women were crushed by the Northwestern Mounted Police, the fore-runners of those cheerful, helpful, red-coated Mounties.

Repression and its side effects are central to Maddin’s work. His characters lust for their mothers and fathers, display all manners of compulsions and obsessions, lose the use of their limbs, fall into catatonic states, attempt to re-enact the trauma of their childhoods and are haunted by ghosts. His films look like some aged celluloid reel – his signature black-and-white Super 8 film, blown up to 35 mm and shot with lenses that have been smeared with Vaseline – being run off a clattering projector, with visible splices, short coloured scenes that look like they were shot in ancient Technicolour, and deliberately fuzzed-out soundtracks. Could there be a better visual representation of some buried memory, drawn out by some pipe-smoking German-accented analyst?

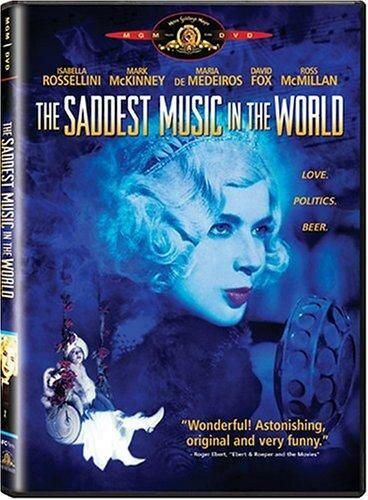

You will find yourself laughing a strange, alienated laughter while trying to follow Maddin’s wild leaps of dream logic. For example, in his The Saddest Music In The World, beer baroness Helen gets a new set of glass legs full of beer from her ex-lover Fyodor, which she lost after he drunkenly amputated the wrong leg, after she was injured in a car accident where she was going down on Fyodor’s son Chester while he was driving and Fyodor stepped out in front of the car. (Did you follow all that, or were you distracted by the image of sexy glass legs overflowing with beer? Don’t worry, that’s what you’re supposed to do when watching a Maddin film.)

For his part, Chester has rejected the frozen land of his birth and embraced the Stars and Stripes to become a sleazy Broadway producer complete with nymphomaniac girlfriend (who is also his brother Roderick’s missing wife). He’s back in Winnipeg, the three-time champion in the saddest city on Earth sweepstakes, for a competition to determine which country has the saddest music in the world. Conspiring with Helen to rig the contest in his favour, Chester turns the competition into a literal battle to the death with his pathetic father and his resentful brother, who dons the black garb of “Gavrillo the Great” and represents Serbia in the competition.

Roderick never fires a pistol at random into a crowd, and Fyodor is by no means his selfish namesake in The Brothers Karamazov, warbling “Red Maple Leaves” on a legless piano while dressed in his WWI uniform, but the literary and artistic allusions are there for those high-minded folk. For those who just wish to see an absurdist Marcel Duchamp mustache drawn on everything, we’ve got fortune tellers who consult their tapeworms for predictions and gaze into blocks of Winnipeg ice instead of crystal balls, and an appropriately daffy performance by Mark McKinney as Chester. We’ll meet McKinney, who is one-fifth of similarly Dadaist Canadian comedy troupe The Kids In The Hall, and his looney comrades again in a future installment, but I think you get the point: Maddin is but one of many Canadian comics who follow the lead of Alan Moore’s Joker, whose song-and-dance number in The Killing Joke advises the reader, “if life should treat you bad… don’t get even, get mad!”

Next on our list of Canadian filmmakers is Atom Egoyan, who responds to trauma in yet another way: with slow, sad paralysis.

*****

See the previous installments in the series:

Part 1 on Heroes: ‘Scott Pilgrim Vs The World’ Vs Terrance Denby and ‘Sidequest’

Part 2 on “Humour”: The Libertarian Fantasy of ‘Letterkenny’

Part 3 on Graphic Novel Nihilism: The Harsh Truths of ‘Essex County’

Part 4 on Spawn and Wolverine: Banished From The Promised Land: A Tale of Two Canadian Anti-Heroes

Part 5 on Science Fiction Dystopias: Inside Quebec’s – and Canada’s – Replicant Culture

Part 6 on Animation: The Garrison Mentality: More Than Meets The Eye

Part 7 on Pop Music: How To Build A Successful Canadian Musical Act

Part 8 on Anne of Green Gables and The Traumatized Artist: Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Treacherous Alpine Path

Part 9 on Avoiding the Serious: Mordecai Richler, Montreal, And Gritty Realism

Part 10 on Southern Ontario Gothic: The Marriage of the Mundane and the Fantastic

Part 11 on Margaret Atwood’s Reign of Terror: Literary Tyranny and The Handmaid’s Tale

Part 12 on the First Nations Fraud: Whitewashing Genocide: Truth, Lies, and Joseph Boyden

Part 13 on the inventive Esi Edugyan: A Novel I Cannot Recommend Enough

Part 14 on Generation X Origins: Douglas Coupland And The Hopeful (?) Future Of Canadian (?) Culture

Part 15 on Jordan Peterson Rising: Canadian Culture Creators And The Intellectual Dark Web

Part 16 on The Awkward Quiet: David Cronenberg’s Silent Hell

Comments

Leave a Reply