Down the aimless streets of Toronto in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World and through the idyllic back country of Letterkenny, lies the way to understanding the way Canadians see themselves, or at least would like to be seen. Both these works are about keeping up a carefully crafted image: the studied apathy and hipsterdom of the big city, and the carefully cultivated simplicity of the country.

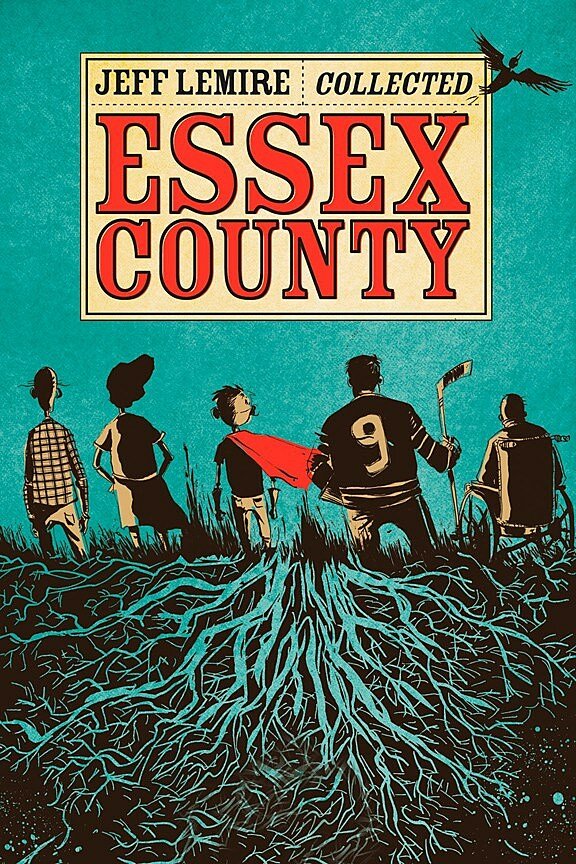

But beneath these polished exteriors (that do their best to not appear polished) lies the haunted world of Jeff Lemire’s Essex County. This is the Canada that we don’t talk about, rendered in stark black and white inks.

When this three-volume compilation was nominated for a Harvey award for Best New Talent in 2008, it vaulted Canadian cartooning onto the world stage and forced Canadian cultural guardians – who had previously considered “comic books” as unworthy of recognition – to take notice. Seven years later, the CBC, our public broadcaster and cultural arbiter, will adapt the graphic novel into a miniseries, elevating Lemire’s characters to the same heights as Anne of Green Gables.

So, what kind of horrors dot Lemire’s snow-covered isolated landscape? Demons? Cults? Serial killers? Nothing so fanciful. The three stories that make up Essex County are as simple and relatable as anything in Scott Pilgrim or Letterkenny… or really, anything we’re likely to find within Canadian culture, or any culture. The first deals with a young boy’s friendship with a gas station owner as they bond over comic books, the second recounts a slow drifting apart and coming back together of two hockey-playing brothers, and the third follows a querulous nurse as she digs into her past and the history of her community. That’s it.

And yet, the darkness and horror are there, in the long silences between conversations, in the random acts of misfortune (fires, farm accidents, car crashes, sports injuries) that ruin lives forever, and in the brief but terrifying eruptions of long-suppressed emotions, only to be quickly silenced once again, for the people of Essex County understand that it does no good to rail against the unfairness of it all.

There is more than a passing resemblance here to Craig Thompson’s Blankets, as both epics were published by the same country, Top Shelf Productions. But while Thompson’s tale of faith and heartbreak mixes sweet moments in with the bitter, Lemire’s moments of joy are few and far between. It’s far more evocative of the classic American short story, Ethan Frome.

Lemire has etched this learned helplessness in their mostly blank and weathered faces. The black, expressionless beady eyes, and the noses that are either thin and pointed or enormously broad make them look more like woodland prey – beavers, ducks, raccoons – than people. There are few smiles. Quietly, they sit, heads bowed in prayer or just downcast, as a cross remains fixed above a dinner table, or first radios, then TV’s broadcast hockey games. Decades pass and people age, but the endless white spaces and old buildings remain unchanged. Nurse Anne Quenneville grows into a younger clone of her grandmother, the Sister Margaret Byrne, while generations of the hockey-loving Lebeufs fall one by one to injuries without achieving the superstardom for which they seemed destined. By the time old Lou Lebeuf is recounting his life in the compilation’s second act, the ghosts of the past are stepping in and out of the present seamlessly. The story encompasses a century, but time seems to stand still, with characters leaving and coming back to Essex County after sojourns in the big city which were intended to be escapes, while dying mothers and fathers pass on their last wishes and memories, and the associated burdens, to their surviving relatives.

These are characters in desperate need of escape, or a salvation that never comes. Young Lester, an orphan living with his Uncle Ken, must imagine himself pursued by aliens as he skulks around Essex County in a domino mask, drawing crude but heartfelt Captain Canada comics (reproduced in full). Old Lou keeps mementos of his hockey playing days in a box which he periodically returns to when the guilt of his past sins becomes too painful. And the formidable Sister Margaret, who is forced to lead her charge of orphans on a harrowing trek through the snow, becomes a silent old woman, long having since set aside her vows, who listens to her granddaughter Anne fret about whether she makes any difference at all in her patients’ lives.

It is almost as if daring to dream, to want something more, is tempting disaster. We see Lou leaping through the air after scoring a game-winning goal, in an obvious nod to the famous photo of Canadian hockey icon Bobby Orr celebrating his 1970 Stanley Cup game-winner. A few pages later, he’s back on the farm, losing his hearing and pushing his resentful older brother Vince around in a wheelchair. “You’ve always done what you wanted,” accuses Vince, referencing an ancient wrong done to him that’s gone unspoken for decades.

The people of Essex County are unable to accept the pointlessness of their own existence. They sincerely seek meaning – in comic books, in fantasy, in hockey, in faith, in family relationships. Yet even without any cause for hope, repeatedly crushed by circumstance and tragedy, they still reach for something beyond their narrow lives. You see a brave caretaker make the ultimate sacrifice, setting in motion the entire action of the trilogy. You see Lou cradling his dying brother, as the ghosts of their old team join them for one last salute, tapping their sticks on the ground. And when the true meaning of young Lester’s bond with gas station owner Jimmy is revealed, it’s hard not to feel that, at long last, we have found some moral centre at the dark heart of Canadian culture. As the final pages turn and the last image of a raven ascending free into the white sky is seen, it’s hard not to feel real hope… though what exactly is to be hoped for is unclear.

For a more obvious moral choice, then, we must follow in the footsteps of many real-life Canadians and go abroad. We will do so in the next installment, where we follow the jagged arcs of two Canadian comic-book anti-heroes: Spawn and Wolverine.

****

Part 1 on Heroes:‘Scott Pilgrim Vs The World’ Vs Terrance Denby and ‘Sidequest’

Part 2 on “Humour”: The Libertarian Fantasy of ‘Letterkenny’

Comments

Leave a Reply