The ongoing weekly serial continues. Click here for the introduction, here for Part 1, here for part 2, here for part 3, here for part 4, here for part 5, and here for part 6.

Chapter Twelve

When I did finally step on Gebian soil, the gravity didn’t bother me. The Columbus gradually acclimated everyone on board by bumping up the artificial gravity one percent every month. I heard plenty of complaints about this during the trip, typically from earthling tourists whose daily exercise regiment consisted of walking back and forth to the dining facility.

I considered them less than credible on the matter.

I overcompensated by spending more time than I should have in the spacecraft’s weight room. Now, I know what you’re thinking: how does someone my size lift weights designed for much larger people? The answer is, very carefully. I spoke with the bot attendant and had it make a few special accommodations for me. It also insisted on hovering nearby while I worked out, but I never allowed it to intervene, even when I struggled to put up heavy – for me – weights.

I had my pride to think about.

Upon landing in New Jerusalem, I took a car to an address Kyle had forced me to memorize, and along the way, I saw the fetid heart of the city for the first time.

There aren’t many ‘bad’ parts of Winnipeg. There were slums in Cairo, but it was an orderly, modern city for the most part. New Jerusalem was, from end to end, a shit hole. The entire ride from the spaceport to the safe house was like taking a trip back in time. Everything was in disrepair, from the car I rode in to the streets it rolled over, from the dilapidated tenement buildings crowded between those streets to the dingy clothes on the people milling about.

The people! They looked broken. Their vacant eyes watched the car roll past with a toxic mix of resignation and contempt I hadn’t seen in the passengers aboard the Columbus.

The safe house was some kilometers away from the epicenter of the sadness, on a quiet dead-end street. Near the front door stood a tree unlike any I’d ever seen on Earth. It didn’t have a central trunk supporting branches and leaves. Instead, it appeared to have been assembled in reverse. From leaves suspended twenty meters in the air grew branches snaking down and wrapping around each other to form a structural center of sorts. Leaves closer to the ground were held aloft by bifurcated branches, attaching themselves to a widening central trunk and descending to the ground to provide additional anchor points. The result was a single tree with multiple trunks that had evolved, I surmised, to adapt to the planet’s gravity.

As I passed underneath, I noticed a small flock of Starlings perched in the branches above.

They were singing.

The safe house was an insulated, concealed node in Gabriel’s network of shelters. If someone came to an open, public shelter seeking help and there was reason to believe their life was in danger, they were sent to a safe house. Some stayed for days. Others, for weeks or months. The woman who answered the door had been at this safe house for over a year and had become its manager.

She would also, in short order, become my wife.

I wouldn’t call her classically beautiful. Every age defines this emergent standard differently, and even though she didn’t quite fit the current definition, I found her incredibly alluring. A little on the tall side — and not just for me — her straight, shiny dark hair framed a distinctive, macilent face. Her front teeth were yellow and slightly askew, and her large, dark eyes beckoned me.

I won’t lie and say it was love at first sight. But it was, for me at least, an instant attraction.

“I’ve been waiting for you,” she announced.

“I’m glad,” I smiled, and she let me in.

I won’t tell you her real name. In fact, to keep their families safe, I won’t use the real names of anyone I worked with on Geb. Instead, I’ll use their shelter names.

Early on, Gabriel’s safe houses re-named guests for their protection. Gebian culture is gossipy, and it’s far too easy to know far too much about your neighbors.

Since Geb was named for the Egyptian God of the Earth, each resident chose their new name from a list of mythological Egyptian gods and goddesses. My wife chose Sekmet, the goddess of lions, fire, and vengeance.

As I came to find out, the name suited her well.

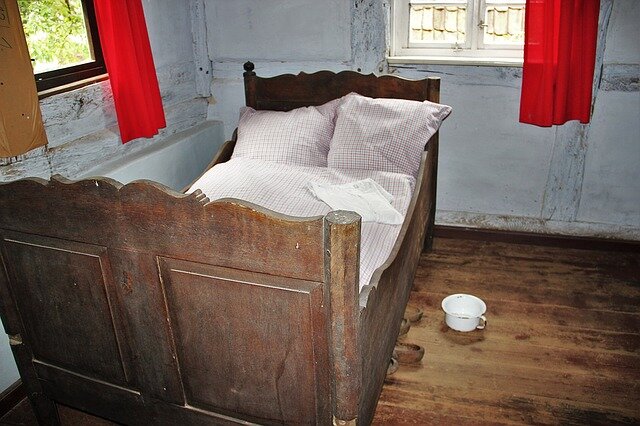

She showed me to my room on the second floor. About the same size as the apartment on the Columbus, it was sparsely furnished with a single bed, a desk, chair, and chest of drawers.

“It’s not much,” she said, apologizing for the state of the room with her eyes. “But you won’t be here long. I’m just down the hall in room twenty-seven if you need anything.”

“Why won’t I be here long?”

She appeared confused. “You’re returning to Earth right away.”

“No, I’m not.” I dropped and climbed on the bed, bouncing up and down, impulsively making a decision I’d been agonizing over for the last eleven months.

Here’s the problem. I needed help. If the plan I’d devised had any chance of success, I’d need a confidant on Geb. A trusted Lieutenant. Someone to assist me in navigating a new planet and a new culture. I knew the safe house was an excellent place to start searching. It’s much easier to convince someone to harm a society if they’ve already been rejected by it. People content with their lives rarely want to risk a change. And in the moment, I thought, who better to try first than the sexy woman running the place?

“But,” she stammered. “I got a message.”

“I know. I received one just like it. I’ve chosen not to comply. How much do you know about me?”

She leaned against the doorjamb and crossed her long arms. “I know you work for Gabriel. I know there were supposed to be two of you. And I don’t know what you two had planned, but I assume whatever it was fell through.”

“What do you do for dinner around here?”

“Me? Or people in general?”

“Just you.”

“I usually make something in the kitchen downstairs.”

This sounded too public. “Is there somewhere we can eat and talk without being overheard?”

“My room,” she answered, then blushed. “Or here. Anywhere but the dining room. It’s usually filled with people.”

“Okay. Let’s meet downstairs in an hour. We’ll cook something and bring it here. Sound good?”

“See you in an hour,” she closed the door behind her.

***

At the appointed time, I went downstairs and weaved my way through the tables in the dining room. Two women in the corner looked up from their steaming cups of tea to gawk as I strutted past. They shared the same expression I’d grown accustomed to: part surprise, part awe. I nodded their way and slipped into the kitchen.

Sekmet was there, chopping carrots on the countertop.

“Can I help?” I asked.

“No. Pull up a chair and watch. I’m making a traditional Gebian dish.”

I spotted a stool to my left, pushed it over to the counter, and clambered up. “What is it?”

“It’s called goulash.”

“Cool. We have that on Earth, too.”

“Maybe, but it originated here. When people first came to Geb, there wasn’t much to eat. They put whatever they had into a pot, added broth and seasonings, and called it goulash. Everyone has their own recipe now, and they all think theirs is the best. This is my grandmother’s recipe, and it is the best.”

She laughed and scooped the carrots into a pot on the stove before peeling the potatoes.

“Did you grow up here in New Jerusalem?” I asked.

“I did. In the Kala neighborhood on the other side of the city.”

“How did you end up working at the shelter?”

“The same way everyone does. I ran away from my home,” she answered, thwacking a potato in half.

“Why?” I blurted out, then backtracked. “Sorry, you don’t have to tell me.”

“It’s okay. I tell the story to everyone who walks in the front door. It is easier to trust someone who’s been through the same hell as you.”

“Will you tell it to me?” I asked as she rammed her blade through another potato and into the cutting board below. “Maybe put down the knife first.”

She laughed and threw cubed potatoes into the pot. “Before I do, you have to pick a new name. The list is out front.” She pointed the knife in the direction of the front door.

“I don’t need to look. I’ve already chosen a name.”

“Really? Which?”

“Horus.”

“Horus.” She slammed the knife into the cutting board, point first, and it stayed there, gently wobbling. “How interesting.”

***

Half an hour later, we were back in my room. Sekmet finished her goulash and pushed the bowl away.

“When I was twelve,” she began, “I wanted to be a lawyer. My dad is a judge here in the city, and I wanted to be just like him. No, better than him. Except he didn’t want me to study law. It is his profession. A man’s profession. So, when he said I couldn’t be a lawyer, I thought about it for a long time and decided to be a doctor instead. Now, to get into medicine here, you have to attend a special school that only accepts able children with good grades. I could have gone to that school. I had the marks, but again he said no.”

“Why?”

“Because I am a girl. I’m supposed to get married to a lawyer or a doctor, not become one myself. But I disagree with this, so when I got to college, I enrolled in medical courses instead of the art courses my father wanted. When he found out, he pulled me out of school. A judge has a lot of power here. He forced me to live at home where I was a prisoner.”

“How did you get away?”

“He beat me. It started when I was young. He told me I was worthless and that he wished he’d had a son instead. I tried to show him I was not worthless. I studied hard in school and did everything he wanted around the house, but he still beat me. One day I made him coffee, because he asked me to. When I brought it to him, he threw it at me. It was boiling hot and burned my face and neck, and when I asked him why he did it, he said, ‘This is because I have to ask you to bring me coffee.'”

“Were you okay?” I leaned forward to look for burn marks but saw none.

“No! I was not okay! I told him I needed to go to the hospital, and he called me names and told me to go there myself. So, I left and have not been back.”

“That’s one of the most inhuman stories I’ve ever heard,” I declared.

“I hear worse almost every day.”

“I’m glad you’re done with him.”

“I’ll never be done with him. If he ever finds me, he will lock me up again. Or kill me.”

“What? Why?”

“I left the Prostledite faith. I disobeyed him and charted my own course. Each is a death sentence here, but both together….” She waved her hand in front of her face. “I’m tired of hearing myself talk. It’s your turn. I want to know all about Horus and why he doesn’t want to leave Geb.”

For the next twenty minutes, I told her an abbreviated version of my story. She appeared interested and engaged, asking questions and laughing at my mediocre attempts at humor. But her demeanor changed when I outlined Gabriel’s offer, his three rules, the time I spent training with Kyle, and my decision to leave Earth. Instead of looking at me, her eyes dropped to the table between us, and her shoulders slumped.

“About a month into the trip,” I continued, determined to finish my pitch. “I received a message from Gabriel. He said the others who’d planned to meet us here backed out when they learned of Kyle’s death. He said he was reassessing the entire plan and couldn’t ask me to stay on Geb while he did. Reading between the lines, I knew this meant he was done with the whole thing. I didn’t respond for a long time. I just sat on it and turned it over in my mind. I always thought there was something a little off about his plan. It was good. It was very good. And it might have even worked. But it wasn’t perfect. And then, about halfway into the trip, the answer hit me. I realized what was wrong and how to fix it. And now I’m here, hoping to bring you into my trust, hoping you can get on board with this idea, and hoping you can help me find people to see it through to the end.”

I outlined my plan, then stopped and let the silence settle in.

“You want to become a God,” she said, finally.

“Nope,” I shook my head. “Just a prophet. A long-dead prophet.”

“It might work if you didn’t talk. You’re the same size, and you look exactly like him. But nothing else fits. You don’t sound alike. Your Gebian is horrible. And Augur would never start a war on his own people.”

“He would if they weren’t listening to him. Do you really believe he commands his followers to kill people on Earth?”

“What’s written in the Heka is not a matter of belief.”

My lips curled up in a smile. This was the moment of truth. This was the revelation that had slapped me in the face on the Columbus. “Let’s change the Heka.”

She furrowed her brow. She didn’t laugh. I expected her to find the suggestion that we could change what’s written in the Prosledite holy book terribly funny. Instead, she asked a serious question. “And how do you propose we do that?”

So I laid out the final act. The coup de grace. The last, audacious and, in all probability, stupid act that could change the Prosledite region once and for all.

Only then did she burst out laughing.

“You Earthlings are all the same,” she said, finally, wiping her eyes with her shirt-sleeves — except instead of Earthling, she used that word I hate. “All you ever think about is you.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Of course not. Try to look at it from my perspective. You come here and ask me to risk my life to kill people on my home planet, all to prepare for a futile gesture that has zero chance of success, and the only reason you give is you think it will somehow stop terrorist attacks on Earth. Have I got that right? Here’s my question, what’s in it for me?”

“Look, you don’t have to–”

“I’m not finished.” She slapped her hand on the table. “You want to change how people think, fine. So do I. But you couldn’t pay me to care about that little planet of yours. If it blew up tomorrow, the universe would be a better place. I do care about Geb. I desperately want things here to change. And if you want people to join you, that’s what you have to promise them.”

“Terror on Earth is the reason I’m here. They–”

“People are blowing shit up on your planet for the same reason my father wants to kill me. Religion. We both want to change it, but for different reasons. If you listen to me and ditch all the talk about Earth, and for Augur’s sake, never, ever tell them about that final stunt, you might get people to come along.”

Over the next few months, I came to recognize her argumentative style always originated from a place of love. But having just met her earlier that day, I was confused and scared, thinking I’d destroyed any hope of her joining me.

“You want me to lie to them?” I asked.

“I’m saying we need to work on your sales pitch before I introduce you to anyone else.”

“You’re going to help me?”

“We also need to work on your language skills.”

“Is my Gebian that bad?”

“Worse than bad.”

“Alright, you could be my language coach. You don’t have to kill anyone. You could stay here and run the shelter–”

“No man tells me what I will do!” She jumped out of her seat and towered over me, wagging her finger in my face. “If I’m in, I’m in all the way. ”

“Then you’re in.” I was both frightened and relieved.

“On one condition. No one kills my father but me.”

“Killing your father isn’t part of the plan.”

“I don’t care,” her face was deadly serious. “No one else kills him.”

“He’s all yours.” How could I not agree to an irrelevant request?

“Good. How many others do you need?”

“I think we should start small with a core group of four or five and branch out as we need help. But I’m open to suggestions. I haven’t done anything like this before.”

“Tomorrow night. A group of ex-Prosledites is meeting downstairs. I’ll introduce you to a few people.”

“They must be people you trust. They can’t go running to the authorities, telling them what we’re up to.”

She threw her head back and snorted. “These people would be arrested if they went to the authorities. You have nothing to fear.”

“Very well. I trust you. We are not related by blood, but we are now related by shared experience and friendship.” Ever since I heard these words from Alan on the Columbus, I’d planned to use them to help bring me closer to the people I recruited, making it less likely they would turn on me later.

I thought the words might have the same effect on Sekmet that they’d had on me.

They didn’t.

“Wow.” She shook her head. “You did not just say that.”

“What’s wrong?”

“We’ve known each other, what, a couple of hours? You have to know someone for months or years before you roll out that line.”

“I didn’t, ahh…” I stammered. “I was just trying–”

“Take me to bed.”

“Huh?”

“After we’ve had that shared experience, try it again and see how it works.”

Every platelet of blood in my body rushed to my face. I didn’t quite understand how we reached this point – a few minutes before, I thought she was disgusted with me – but it had been a long time since I’d taken a girl to bed. I couldn’t turn down the opportunity.

“Okay,” I hopped down and held out my hand. “Any other cultural hoops to jump through, or is just saying let’s go to bed enough?”

“That’ll do,” she said and slipped her hand into mine.

***

At some point during the night, I opened my eyes and realized Sekmet was awake. Street light flowed freely into the room through uncovered windows, and I saw her propped up on her elbow, looking out at the tree guarding the front door.

“What kind of tree is that?” I asked, stuffing a pillow behind my back and sitting up.

“It is a Retusa Tree. The iconic Gebian tree.”

“Why is it iconic?”

“During the battle of Konstantini, Augur hid among the many trunks of the Retusa Tree, waiting for his enemies to pass. When they did, he emerged and defeated them. This is how the legend began. Behind a Retusa Tree, you are safe. Your enemies cannot harm you.”

“But you can harm them.”

“Absolutely, you can.”

We sat for a few moments watching the leaves rustle gently in the night breeze. I knew there was something I had to do before we started on this journey together, but I didn’t want to do it.

“Can I say something without you interrupting me?” I asked.

“Probably not.”

“I’ll say it anyway because the rules between us must be clear. There can only be one leader, and that has to be me. I lead. You follow. It won’t work any other way.” Kyle had drilled that into me, and I felt like Sekmet, and I needed to come to the same understanding.

“Let me be clear. If you want my help, we need to be partners. Equal partners. We discuss things and make decisions together.”

I could live with a partner. “I like your way better,” I said.

“Of course you do,” she leaned over and kissed my forehead. “Now lie down. I don’t sleep very well at night, but I’ll feel better if I know I’m not keeping you awake.”

A long time later, I felt her lay back and pull me in tight to her body. She wrapped her arms around me and kissed the top of my head.

There is nothing better in the world than feeling safe, secure and loved.

I felt like I was home.

Chapter Thirteen

The next night I sat in the back corner of the dining room while the ex-Prosledite Society of New Jerusalem held their weekly meeting.

All eight of them.

It was easy to figure out why there were so few. Their onerous security protocols weeded out everyone except those most dedicated to their cause. They weren’t even going to let me in until Sekmet threatened to kick them all out of the shelter.

She could be persuasive in her own way.

The group dedicated the second half of the meeting to the vetting of two prospective members. Those two had been followed and surveilled and appeared to be clean, but Nut, the group’s leader, erred on the side of caution and wanted to wait another week before deciding. For a group hoping to promote atheism as a practical alternative to the religiosity of Geb, operating in the shadows seemed a strange strategy to pursue, but it was the only one available to them. Atheism was not only illegal on Geb, it was punishable by death.

After the meeting, Sekmet introduced me to Ra and Kuk. Fraternal twins in their late twenties, both were the same height and had dark hair and green eyes but were otherwise polar opposites. During the meeting, I watched them push and poke and prod each other so much I prayed to God – during an atheist meeting – they weren’t the ones Sekmet wanted me to meet.

Reluctantly, I led them upstairs and into my room. Sekmet closed the door behind us, and they plopped down next to each other on the bed. After some minor jostling for position, they looked at me in anticipation.

I gave them the pitch Sekmet and I had developed and practiced earlier in the day.

“I’ll get straight to the point,” I began. “I’m starting a revolution, and I want you to join me. Religion has become a cancer on this planet. Instead of joy, it creates fear. Instead of hope, it creates despair. And instead of prosperity, all you need to do is look around New Jerusalem to see it has created hardship. We can do so much better, but we have to break the stranglehold religion has on our politics and economics.” The economics angle was Sekmet’s idea. Most of the people we’d meet were dirt poor.

“Revolutions are rarely bloodless,” I continued, “and this one won’t be, either. But it will have rules. Hard and fast rules you must agree to follow. One, for every person murdered on Geb or Earth, a member of the Gebian government, military, or religious apparatus dies. Two, we will explain to everyone on both planets what we’re doing and why. And three, if their attacks stop, ours stop. Do you understand?”

To their credit, they fidgeted only minimally while I spoke, and at the end, Ra raised his hand.

“What are you doing?” Kuk asked him.

“I have a question.”

“We’re not in school, stupid, just ask.” Kuk slapped him on the back of the head.

Ra retaliated with a hard punch to Kuk’s thigh, then Kuk pushed him back on the bed.

“Boys!” I yelled. The pair sat back up, watching each other out of the side of their eyes. “Not now, please. Kick the shit out of each other on your own time.”

“Ra, what is your question?” Sekmet asked.

“What number are we at? Has the clock started yet?”

“What are you talking about, jackass?” Kuk taunted him.

“Stops.” Ra closed his hand into a fist. “They know what I’m talking about.”

“I do know,” I said. “You’re asking about the first rule, right? You want to know how many people we have to kill on Geb.”

“That’s right.”

“That’s a great question,” I watched Ra look defiantly at his brother. “The answer is we haven’t started yet. First, I need to record a message explaining our rules. Once our intentions are public, we start the clock.”

“See,” Ra said.

“How do you define murder?” Kuk asked.

“I don’t follow,” I replied.

“You said you only respond to people who are murdered on Geb, but we’ve seen friends of ours–”

“Teresa, Marty,” Ra interrupted.

“Liu,” Kuk continued, “who all died after leaving the religion, but their deaths weren’t investigated. Nobody cared enough. Where are they in this calculus?”

I looked to Sekmet. This was a detail we hadn’t discussed.

“Marty,” Sekmet answered. “Died rock climbing. Yes, his father was there, but everyone who testified said it was an accident. Liu killed herself. Now, we all know it was because of what her husband did to her, but it wasn’t murder. The Prosledites committing attacks on Earth are very clear. And there are religious murders here which are also very clear. We can’t let the edge cases define our strategy. And if this revolution works, it will fundamentally change the world, and we’ll avenge them all the same.”

This might have been the moment I fell in love with her. Here she was, just a day after we met, explaining our revolutionary idea better than I ever could have. I had agreed not to mention the endgame — changing the Heka — after she had agreed to help me carry it out. She didn’t believe it could happen. Hell, I did it, and I still don’t believe it happened. But we both believed it would turn people off, so we kept it to ourselves.

The twins listened stoically, not moving an inch, then they looked at each other and nodded.

“Many people have been waiting for something like this,” Ra said.

“The real question isn’t why someone didn’t do this years ago,” Kuk added.

“It’s your fault,” Ra jabbed his brother in the ribs.

“Enough! They already yelled at us once.”

“So you’re with us?” I asked, unsure whether I should be excited about the prospect of working with the twins.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Sekmet announced, “like finding weapons and ammunition and explosives.”

“We can help with that,” Kuk chimed in, “Ra used to be a soldier boy.”

“Are you ever not an asshole?” Ra pinched the skin on Kuk’s tricep.

“Ow!” Kuk swatted Ra’s hand away.

I looked at Sekmet and threw my hands up.

“I don’t know if this will work, guys,” Sekmet said.

“No, no, no. Wait!” Kuk declared, holding his hands out in front of him.

“We’ll be good, promise,” Ra added.

I looked back at Sekmet and shrugged my shoulders.

“What were you saying about weapons?” She asked.

***

When my baggage arrived from the Columbus, Sekmet and I – and by this, I mean just Sekmet – decided to use my room as a storage area and workspace. I’d been sleeping in her room every night anyway, so I didn’t argue. I gave her a quick orientation as we unpacked.

“What’s in this trunk?” She wondered, pulling it into the room.

I looked at the manifest. “Cash.”

“This whole thing is full of cash?”

“Yep,” I nodded.

“Maybe we should put this where we can get to it.”

“Your room?”

“Great idea!” she smiled and pushed the trunk back into the hallway.

We opened cases full of communications gear, inert explosive precursors, augmented vision devices, and other tactical gear. These we inventoried and put away in no time, but Sekmet became obsessed with the birds.

“So this is what you were going on about.” She said with a sense of wonder. “And you’ll teach me to fly them?”

“Of course. With these birds, my dear, we are going to make history.”

Once we finished putting the gear away, we went back downstairs and had dinner. I cooked while Sekmet chatted with Isis and Ma’at, two refugees who’d come to the shelter the day before me. They got up to leave as I brought out our plates.

“Poor girls,” Sekmet said as I sat across from her.

“How come?”

“What is this?” She asked, looking at her plate.

“Just eat. If you like it, I’ll tell you.”

“Their husbands divorced them. They were in a shelter across town, but their husbands found them, so they came here. I told them where to look for work, but they want to go to Earth instead.”

“Don’t you send people to Earth?”

“Sometimes. It depends on how much trouble they’re in. But I can’t ask for money to send two people who are just lazy.”

“Would they be willing to join us?”

“Do you not listen to me? I just said they don’t want to work.”

“What will you do with them?” I asked.

“I will point them in the right direction, but I won’t drag them to their destination. If they haven’t found a job or a place to live after two weeks, they have to leave.”

“Even if they have no place to go?”

“Some time on the street may motivate them. Speaking of motivation, you need to write your speech for the first stream so I can correct it.”

“How is that motivation? And how do you know it’s not perfect already?”

“If it’s perfect, then you can practice in front of me. Naked.”

I spit out my food. “Naked? Why?”

“That’s how you get comfortable speaking in front of a camera.”

“I think you have it backward,” I said. “On Earth, the advice is much different.”

“The way you do it on Earth is always the right way? Did you ever think maybe you’re the ones who have it backward?” She grimaced and dropped her fork on the plate. “What is this?”

“If you don’t like it, I’m not telling.”

“That makes no sense.”

I shrugged.

“You’re never cooking again.”

“Promise?”

We cleaned up and went back upstairs, and crawled into bed. But she didn’t sleep. She sat, her back against a pillow, stroking my hair as I drifted off.

***

When I woke, Sekmet was shaking me, her face inches from mine, while blue lights jumped around the room at weird angles.

“Come downstairs in five minutes! Do you understand me? No matter what you hear. Five minutes!”

She let go of my shoulders and ran out of the room. I scooted down the bed and leaned forward to peer out the window. A gaggle of policemen – not bots, real people – in black uniforms stood beneath the Retusa tree and pointed to the front door. Beyond, on the street, two parked New Jerusalem Police vans blocked traffic.

I heard the front door open and saw officers rush toward it, in a hurry to get inside. They couldn’t be looking for me. We hadn’t done anything yet, and nobody knew who I was. Sekmet didn’t tell me to run or hide. In fact, she told me to come downstairs no matter what I heard.

I threw on pants and a shirt and padded down the hallway. Stopping at the top of the staircase, I strained to hear what was happening below.

“She’s not here. There is no one here,” Sekmet pleaded.

“She was spotted walking down this street earlier today,” a man’s voice replied.

“So that means she’s here, now? You haven’t gotten any smarter since the last time you were here.”

“That’s it. Search the place!”

“You need permission from my husband first.”

“You’re married?”

A moment of panic enveloped me. I had no idea I was sleeping with married woman.

“He’ll be down soon.”

The panic subsided as I put two and two together and realized she was talking about me.

“You weren’t married last time we were here.”

“Things change.”

“Things might, but you don’t.”

“See for yourself. He’ll be here any second now.”

This had to be my cue, and even though I didn’t know what to do when I arrived, I started down anyway. At the landing, I turned left and saw an officer standing at the bottom of the staircase looking up at me. His mouth dropped open, and he tapped the officer next to him, who turned my direction as well. Then they both gingerly backed away from the staircase.

I went down three or four more steps then stopped at the point where I was still taller than everyone else in the room. I said nothing but wasn’t trying to be mysterious. My mind was a complete blank.

“There he is,” Sekmet said.

“Excuse me, sir. This woman tells me you are married, is that right?” The officer approached, close enough for me to read the nametape on his uniform: Minkle.

“Do you not believe her, Officer Minkle?”

“Of course I do, sir, but it seems rather sudden.”

“Does it?” I feigned surprise. “How long should a courtship last?”

“That’s not what I mean, sir.” He tried to regain control of the situation. “Look, I’m going to have to ask you to go ahead and permit us to search the shelter. We are looking for two known fugitives.”

“Am I compelled to give you my permission?” I asked, not having a clue what the answer was. The only thing I could think to do at this point was ask questions.

“Well, no. But, the only people who say no are the people with something to hide.”

“Has anyone said no because you insulted their wife?” I looked at Sekmet, desperately hoping she would jump in.

“Sir, I did not mean,” he hung his head and practically bowed in my direction. “If I offended you or your wife, I am sorry.”

“Apology accepted,” I said, then decided to go on offense. “Now, take your men and leave at once. It’s very late.”

“If that is your wish, sir, I will leave. But my men will stay out front, and I’ll be back with a judge. We will search these premises tonight.”

“Darling,” Sekmet said seductively. “I think it would be alright if they sent two men up to check the rooms. Don’t you? And when they don’t find what they are looking for, they can leave. I would hate for these poor men to stay out all night for nothing.”

I nodded, grateful for the assist. “I’m sure you can see why she is my better half, Officer Minkle. Is this proposal acceptable?”

Minkle looked from me to Sekmet then back again. I think he knew he was being played but couldn’t work out the details.

“Yes,” he said through gritted teeth. “Pacquiao, Carrola, head upstairs.”

Two officers moved forward and began climbing the stairs. I stayed put, crossing my arms in the middle of the staircase, forcing them to slide between me and the railing.

Minkle and the rest of the officers milled around the entranceway with their heads down. Sekmet weaved through them and walked up the steps to me. She kissed me on the cheek and whispered, “You’re getting laid for this,” in my ear. I put my arm on her shoulder and waited for the two officers to return.

They should have found five people on the second floor and two on the third, but Sekmet’s demeanor told me they wouldn’t see anyone. Sure enough, a few minutes later, they came marching back down the stairs, shaking their heads.

“There were people here, but they’re long gone,” Carrola reported.

“No one stays here at night, Minkle. That’s our rule.” Sekmet said innocently.

Minkle set his jaw and bowed again in my direction. “Good evening, sir, ma’am. Sorry for the disturbance.” He twirled his finger, and the officers began filing out the front door.

“You’re only doing your job,” I replied and watched him close the door behind him.

I turned to Sekmet. “What the–”

She slapped her hand over my mouth. “Shh,” she hissed, then crept down the stairs toward the front door. She looked through the peephole, engaged the locks, and slammed the horizontal steel bars into place.

Then she turned around and scurried past me up the stairs. I followed, but she was much faster. When I reached the second floor, she was coming out of the storage room.

“They’re gone.”

“Of course they are. They walked out the front door. What are you doing?”

She shook her head. “They hover sometimes. Stay here. I’ll let everyone out.”

She brushed past me and climbed the stairs to the third floor.

“Let everyone out of where?” I asked, but she was gone.

A minute later, Isis and Ma’at descended the stairs in their pajamas, followed by another woman I didn’t know wearing much less. I averted my eyes and paced the hallway, listening to the patter of feet above me until Sekmet returned.

“Ready to go back to bed?” She asked.

“What the hell was that?”

“Inside,” she walked into the bedroom and held the door open.

I followed her, and she closed the door behind us.

“Now, can you tell me what the hell happened?”

“Officer Minkle likes to harass us from time to time. I stall him long enough for everyone to climb into the panic room upstairs. Then the police search, they don’t find anything, and they leave. Happens maybe once a month.”

“Why did you have to tell him we were married?”

“I didn’t,” she said with a twinkle in her eye. “I just wanted to see what you’d do.”

“What if they’d found the money or any of the equipment in the storage room?”

“They’re looking for people, not things. They never go peeking inside of boxes.”

“Why didn’t you tell me about this before? You sent me downstairs blind.”

“C’mon,” she said, patting the mattress next to her. “Let’s go to bed.”

“No. You’re not using sex to get your way out of this.”

“Yes, I am.”

I sighed. Yes, she was.

***

I walked into the bedroom the next afternoon and handed Sekmet the sheet of paper I’d worked on all morning.

“Here’s the message I want to read on the first stream,” I said. “Tell me what you think.”

I say this to the people of Geb. You have disobeyed my orders. God shall judge in the next world. You are not permitted to do so in this one. All violence against those who do not believe in me must stop, or I shall punish the people of Geb. This is your first and only warning. For every person killed in my name on Geb or Earth, one military, government, or religious official will die here. There is nowhere you can hide. I will even the score. Whatsoever you do to the nonbelievers will be done unto you.

“Hand me your pen,” she said.

I gave it to her, and her right hand hovered over the page for a few seconds before she set the pen down and tore the paper in half.

“Start over.”

“What’s wrong with that?” I plucked the two halves out of her hand.

“You sound like Augur’s illiterate bodyguard.”

“You’re exaggerating.”

“Listen,” she put a gentle hand under my chin and pulled my face towards hers. “The Augur I grew up worshipping loves his people. He inspires them. If you want to make them think you are him, you must adopt this persona.”

“These things have to be said. We can’t start killing people without telling them how to make it stop.”

“You’re not hearing me. You don’t have to say it this way.” She took the pieces out of my hand and put them together on the table. “The first thing Augur does is scold his people? He’s been gone for two hundred years. How about a hello? How about thanks for keeping up the faith since I’ve been gone?”

“I didn’t think about that.”

“Of course not, because you’re an idiot.” I knew she meant this in the most loving sense. “You can be disappointed with how people interpret your words, but only after you’ve told them how much you love them. And don’t talk in specifics. This stuff about evening the score, we can use that for our own accounting, but it’s better if they figure that out on their own.”

“Okay,” I took both halves of the paper and crumpled them up. “I’ll re-write it. Promise you’ll help with the inspirational parts.”

“Promise, but it has to be tonight. Ra and Kuk will be here tomorrow with the weapons. And they’re bringing a friend.”

“A friend?”

***

Photo by Pixabay

Comments

Leave a Reply