Note: This is the start of a new weekly sci-fi serial running on Wednesdays. Click here for the introduction to it last week.

Prologue

Two years in the Defense Force taught me nothing about warfare.

This was the conclusion I reached halfway through our first operation when it looked like I would get us all killed.

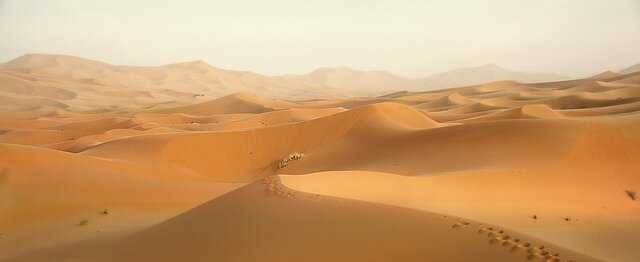

Our target was a small outpost in the middle of the Oken Desert. Years ago, when roving gangs of desert thieves were making trouble, it was a major Prostie supply depot supporting thousands of people all over the desert. But ever since their victory at Nisoor Pass, the Prosties had been slowly shutting it down. Only twelve soldiers were there the night we attacked.

I know. I saw them all.

Our mission was to infiltrate the outpost, take out the soldiers, grab whatever weapons and supplies could fit on the back of a truck, and head back to basecamp. It was supposed to be easy. Something to get us set us up for more complex operations in the future.

We stashed our vehicle on the outskirts of New Jerusalem the night prior and humped in under the cover of darkness. We set up basecamp in a modest cave beneath a rocky outcrop a few kilometers away from the outpost. For a full day we slept and ate and talked and waited and tried to hide how nervous we were about the upcoming attack.

Just before sunset, a few hours before we moved out, I flew the birds over the outpost. Starlings are rarely seen in this part of the desert, and I didn’t want to arouse suspicion, so I only made two passes at altitude then brought them back.

The Prostie outpost was just as Ra described. He was stationed there years earlier. Positioned near the intersection of three desert trails, it boasted perimeter fences five hundred meters long on four sides, along with four guard posts at the corners and one at the sole entrance and exit. Two soldiers manned this entry control point, and neither one looked concerned with anything except keeping cool. They stacked their weapons against the side of the building, removed their long-sleeve shirts and boots, and rolled up their pant legs. Everyone else worked outside the only well-manicured building in sight. Our target building. Situated just inside the outpost near the entrance, its doors and windows were sealed tight.

“That’s the building to hit,” Ra said when I showed him the feed. “It’s air-conditioned. They’ll sleep there.”

At 0200, the five of us started the four-kilometer trek to our starting positions. Ra and Kuk sidled up to the guards near the entrance while Sekmet, Maahes, and I huddled near the perimeter fence on the opposite side. We only had handguns – the loud kind – not the more advanced, silenced stuff we hoped to acquire on this mission. We were five brave, stupid souls, alone and unafraid, thinking we were about to change two worlds.

I have a hard time looking back on that night. There are so many things I would have done differently. It was the beginning of a learning process for me, and all of us, but in this business, you only learn from a mistake if you stay alive. We survived the attack only because of an unstable mixture of hubris and luck.

If I were planning the raid today, I wouldn’t use the same entry points. I would make sure the teams could see at night and communicate with each other. I would plan a diversion, issue a contingency plan in case everything went froggy, and make better use of the birds.

And I would have been on the lookout for the goddamn dogs.

Maahes cut the fence at 0300, according to plan, and the three of us slipped inside and crouch-walked toward the target building.

At precisely 0310, according to plan, Ra and Kuk were supposed to take out the two soldiers at the guard post while we tiptoed into the manicured barracks and killed all the sleeping soldiers inside.

At 0304, the plan disintegrated.

That’s when the dogs began to bark.

I hate dogs. I know that’s kind of like saying I don’t like standard gravity or sunshine or sex, but it’s true. They don’t like me much, either, so the feeling is mutual.

I couldn’t see them. There was only one light in the entire outpost, a single LED shimmering atop the guard post at the entrance. That light also illuminated the barracks building so the guards could walk back and forth without bumping into anything. But none of it splashed back into the space we occupied. We were blind, and the snarling beasts were closing in.

“What do we do?” Sekmet hissed.

“Run!” I yelled and took off as fast as I could toward the light.

A few seconds later I was alone. Maahes and Sekmet were both born on Geb and ran much faster. I heard growling close on my left and whirled around, hoping to catch a glimpse of something to shoot at, but before I could, the lead dog pounced.

The force of the blow hurtled me sideways. I rolled, coming to rest on my right side — my gun side — while the dog whipsawed my left arm, tearing through the fabric of my shirt. I wiggled my right arm out from under me and pulled the trigger blindly in the its direction. The crack of the shot was fantastic, and despite the muted ringing in my ears, I heard a pleasing, painful yelp. I aimed at the yelp and pulled the trigger once more for good measure.

This was the wrong decision.

I should have been worried about the other dogs.

Another one clamped down on my right arm, hard. Pain rocketed through my body, and I whirled around instinctively with my left fist, smashing it in the head. It wouldn’t let go. My arm was screaming, but I could still feel the gun in my hand. I managed to transfer it to my left, stuck the barrel near the base of the dog’s writhing skull, and pulled the trigger. No yelp this time. It went limp and collapsed on top of me.

Only then did I notice a third dog tearing into my right boot, trying to rip my leg off. The pain in my arm was so intense I didn’t know, until much later, whether it did any damage. I raised the gun to fire once more but stopped when I couldn’t get a sight picture.

Dark dog. Dark sky. Dark desert. It was all a dark blur. I might hit the beast, but I had a better-than-average chance of blowing my foot off, too.

Mercifully, I never had to make this decision. In its manic effort to tear my leg from my body, the dog found a tiny sliver of reflected light, enough for Sekmet to aim and fire. She hit it in the hindquarters, and it fell but kept gnawing on my foot until she clubbed it on the head. Once it stopped moving for good, she pulled me to my feet.

“Are you ok?” She asked.

“Fine,” I said through radiating waves of pain. “Where’s Maahes?”

“He’s up ahead. We have to hurry.”

The perimeter lights snapped on as we caught up to Maahes, parked on the ground behind an abandoned building, his knees pulled into his chest. We’d thrown away the element of surprise. The dogs and our gunshots had roused the entire camp.

“It’s over, Horus,” he whined as I took a knee beside him. “We have to go back.”

“We still have a chance,” I said, testing my right arm. It didn’t feel broken, but every little movement sent shards of agony through my shoulder.

I pointed to one corner of the building. “Sekmet, take a peek and see what the Prosties are doing. I’ll check this side.”

I crawled to the right and peered around the corner. There was only one building between us and our target. With the perimeter lights on, it was like midday in the desert, and I could plainly see a group of four Prosties in their underwear, looking anxious and sleepy and fumbling with their weapons. Conscripts. The oldest couldn’t have been more than nineteen. They hadn’t yet seen the dead dogs or us, but it was only a matter of time.

I turned to Sekmet and held up four fingers. She looked back at me and held up five. That meant there were three we couldn’t see. The two at the gate and one other Prostie I couldn’t account for. I prayed Ra and Kuk would take care of them.

I crawled back over to Maahes, who looked like he just wanted to go home.

“Maahes, look at me!” I waited for his timid eyes to meet mine. “Go with Sekmet. There are five on her side. They’ll run this way to find out what happened to the dogs. When they pass, you open fire. Understand?”

He nodded, his wet eyes glued to mine.

“I’ll take the four on my side. Go!”

He crawled reluctantly toward Sekmet while I scrambled back to my corner. Taking another look with my right eye low to the ground, I saw the group begin to move in our direction. But they were creeping along, step by careful step, and my stomach sank as I realized my hasty plan wasn’t going to work. The Prosties wouldn’t blow past, allowing us to shoot them in the back. They were treading carefully, checking all the nooks and crannies along the way. They’d find us and use their superior numbers to kill us all.

Then we got lucky.

Ra told the story later. He and Kuk didn’t take out the guards at 0310 when they were supposed to. They heard the dogs and the gunshots, and they froze, unsure what to do once the plan flew out the window.

They watched soldiers pour out of the barracks while the two guards at the gate grabbed their weapons and joined them. Then an officer, exiting the building last, ordered the guards back to their post. A few seconds later, he ordered the rest of the newly awakened soldiers to sweep the entire compound.

Slowly.

Returning to the entry control point, the two guards watched the excitement, turning their backs to Ra and Kuk, who were hidden safely behind a dune ten meters away.

Kuk said he wanted to kill them right away, but Ra was scared. Ra said the whole thing was his idea. I didn’t care who said what. In the end, they accidentally did the right thing.

They snuck up close to the guards and dropped both with one shot each. Then, using the guard post as cover, they opened fire on the officer. I can’t hit anything at thirty meters with a handgun, and they didn’t do much better. They each fired ten shots before the Prostie went down.

Hearing a flurry of gunfire behind them, every soldier inching toward us on both sides of the building did precisely what they were trained to do. They turned around, dropped to the ground, and pointed their weapons in the direction of enemy contact.

And away from Maahes, Sekmet, and I.

I jumped up and looked at Sekmet. She stared at me, waiting for guidance. I pumped my left arm toward the Prosties and stepped around the corner. The first three never knew what killed them, but the fourth looked directly at me before he died. I saw wide pupils struggling to comprehend the sight before him, and I hesitated longer than I should have.

I think that’s probably natural. Until a few seconds earlier, I’d never killed anyone in my life.

When all four were dead, I heard shots ring out on the other side of the building. I don’t know what took them so long, but when I ran over to check, Sekmet and Maahes were standing over the bodies of five lifeless Prosties.

“Let’s go!” I yelled. “Start loading the truck!”

“Horus!” I turned around to see Ra sprinting toward me. “They called for air support!”

My mind went blank. Before the mission, we didn’t talk much about Gebian air capabilities. There was no point. They didn’t regularly fly over the desert, so the chances of accidentally spotting us were slim. If they received a distress call, however, they could be overhead in a matter of minutes. And we’d be fucked. This was the reason the element of surprise was essential. We were helpless against a Scorpion drone.

“How long?” I asked. The five of us were back together again, everyone looking at me for guidance.

“Five minutes. I just heard them on the radio.”

We had only one option. Run. We’d planned to load as much equipment as we could onto a truck parked near the perimeter fence, but there was no time for that now.

“Everybody grab a weapon and get to the truck. Sekmet, you drive. We need to get out of here fast.”

“Kuk’s the better driver,” she said. “Let him do it.”

Here was something else we hadn’t worked out yet. In the heat of the moment, when the world around you is falling to pieces, a soldier never questions a leader’s orders. Ever.

Even if the two are married.

I don’t care if Sekmet listens to a damn thing I have to say at home — she quite often doesn’t — but at that moment, she should have obeyed me. Period. If I had been inclined, I could have spent the last few minutes of our lives arguing with her until the drone bearing down on us fired one of its guided missiles, ending the argument for good. I was not so inclined, but I sure as hell let her have it when we got home.

Instead of arguing, I ripped a rifle from the dead hands of the soldier behind me and screamed, “Go! Go! Go!”

Ra had assured us Gebian military vehicles don’t have keys, but I still had a moment of panic when I slid into the passenger seat of the truck and saw Kuk next to me waving his arms in the air like a madman.

Ra’s arm shot forward from the back seat, found the START button, and pushed it. The front panel illuminated, and we were off.

At a crawl.

For thirty agonizing seconds that stretched into years, we all watched Kuk back up, roll forward, turn, point the truck toward the exit, then carefully negotiate the meter-high serpentine barriers set up to limit the speed of incoming and outgoing vehicles.

Then we were out, accelerating down an open road. A left at the intersection, and it was a straight shot back to camp. Kuk negotiated the turn without braking.

Sekmet was right, dammit. He was the better driver.

We didn’t need to use headlights. The outpost’s perimeter lights illuminated enough of the desert floor, but this wouldn’t last. I knew we’d transition to darkness soon, and I’d have to make a decision.

“Look for aircraft!” I yelled over shamal-force winds whipping through the cabin. I don’t know why I gave this order. Unless the Scorpion had the words ‘Here I am’ etched in bright neon lights on the side, it would have been impossible to see in the dark sky overhead, but I wanted to do something, even if that something was meaningless.

As we drove on, the light faded. Kuk, struggling to see the trail in front of us, reached for the panel in front of him.

“Not yet!” I slapped his hand away.

Darkness swallowed the road, and Kuk slowed the truck. I had to think. If we turned on the headlights, we would reach basecamp faster, but the aircraft that was now surely overhead would have a better shot at finding us. If we kept the headlights off, we’d have to drive slow, giving the drone more time to find us.

The worst part? We might be dead whatever decision I made.

So I choose speed.

“Hit the lights!”

Bright, white light flooded the desert in front of us, and Kuk mashed down the accelerator once again. I could just see the outline of the outcropping above our camp about a kilometer ahead on the right, and only then did I realize we had another problem.

My original plan called for us to stop at basecamp, load up our equipment – the birds, most importantly – onto the truck and drive it to the outskirts of New Jerusalem. That plan was now shot to hell. We might get to basecamp in one piece, but we’d never make it to New Jerusalem without the Scorpion spotting us.

The truck was the problem. The Gebians knew we hit the outpost and by now probably knew their soldiers were dead, and the truck was gone. As long as we had it, we were a target. If we got out, we might have a chance of making it through this night. There was nothing in it anyway. We could make it back to New Jerusalem the same way we’d made it here. On foot.

“Stop!” I screamed and turned off the headlights.

Kuk slammed on the brakes. I felt the back end of the truck slide and fishtail, but Kuk counter-steered and kept it straight. I promised myself never to let Sekmet know she was right about his driving skills.

“Everybody out,” I said, pushing my door open. “We walk from here.”

To their credit, nobody argued this time. Everyone climbed out without a word.

The darkness was overwhelming. Not even starlight penetrated the overcast sky. I felt the smooth surface of the road underneath my feet but couldn’t see it.

“Quickly,” I said, hoping everyone was close enough to hear me. “Into the rocks on the right. The drone will be looking for the truck. We need to get away from it. The cave is a few hundred meters ahead. We can hide there.”

I started jogging and knocked my left shin on a medium-sized rock as soon as I left the road. It threw me to the sand, and I landed on my right arm, sending a fresh current of pain through my shoulder.

Always the bad arm. Never the good one.

“Are you all right?” I heard Maahes ask.

“I’ll live,” I said, pushing myself back to my feet.

“There’s no reason we have to be silent, right?” Ra asked, somewhere ahead of me. “Follow the sound of my voice. I’ll break trail and–”

There was a flash of light, and a shock wave lifted me off my feet.

Then the world went dark.

The next thing I knew, Sekmet was shaking me.

“Wake up! We have to move!”

She yanked me up and dragged me behind as she dashed through the rocks. I could see again and slowly realized this was due to an eerie orange glow I couldn’t quite place. A moment later, I put it together. The Scorpion had hit the truck with a missile, and it was still burning.

It found us.

Adrenaline raced back into my system, and I willed my legs to run faster.

“Is anyone hurt?” I shouted to Sekmet.

“I don’t think so,” she yelled without stopping. “They’re up ahead.”

The next few minutes were agonizing. I knew the drone was above our heads, watching us, waiting for the right moment to launch another missile. I was living one second at a time, wondering which would be my last.

Sekmet had to stop several times to wait for me. I couldn’t keep up. I urged her to keep going, to leave me behind, but she wouldn’t listen. This time I couldn’t blame her. I wouldn’t have listened to me, either.

Finally, I heard Ra’s voice again, in the distance to my right. “We’re here. We made it to basecamp. Follow the sound of my voice. Keep running. Follow the sound of my voice.”

He grew louder and louder. I rounded a stout boulder and felt a hand grab my shirt and pull me to the right, into the cave.

Then another missile hit where I had been just seconds before. The flash of heat singed the hair on my head, and I was blown farther into the cave, toppling over sprawling bodies. Splinters of rock rained down, and everything sounded like my head had been plunged into a pool of water.

It found us. And it wasn’t going away.

I sat upright and did my best to assess the situation. A Scorpion could stay airborne for days, waiting for us to leave the cave. And whoever remotely controlled it would dispatch ground troops to our location. If we left the cave, another missile would end us, but we couldn’t stay, either. Our only chance was to get that aircraft out of the sky, but we were just five people, on foot, with nothing but handguns and a few assault weapons.

Then I thought about the birds.

I scurried deeper into the cave, vaguely aware of people yelling at me but unable to make out a word they were saying. I knocked a few birds over trying to find the control box before my right arm slammed into it.

Always the bad arm. Always.

I shook off the pain and fumbled with the latches before opening the box. I hit the power button, and blinking status lights illuminated the back end of the cave. Using my good arm, I positioned the VR goggles over my eyes and waited for the start-up sequence to finish. When it did, I was looking through the eyes of the lead Starling.

My own eyes adjusted quickly. The birds’ default night mode was white-hot infrared, and everything except the mouth of the cave was black. I saw four human forms huddled together, their heads turned in my direction. I grabbed the controls and selected Follow the Leader mode without thinking. The birds flew simple and fast and straight in FTL. The last thing I cared about at that moment was stealth.

Then I launched them into the air, skimming the tops of ducking heads before exiting the cave and curving up into the night sky.

I took the birds up high at first to get a sense of the desert around us. In no time, I spotted the remnants of the truck still smoldering on the road and noticed a smaller patch of light near the mouth of the cave where the second missile struck.

Sending the birds higher, I scouted around in all directions to see if anything else was heading our way but saw nothing. The desert looked lifeless.

Then I got lucky for the second time.

A gust of wind pushed the birds upward, and I spotted the Scorpion circling above. It flew low, maybe a thousand meters above the desert floor, banking in a slow, circular arc. I’d seen pictures before but had never seen one in flight. Its long, sweeping wings, still carrying one missile each, protruded from a fuselage that was larger at the front and tapered off toward the rear where its engine powered it through the sky.

As I studied it, an idea formed.

I matched the drone’s altitude and watched it glide in a racetrack pattern. It didn’t change course randomly. It circled the same patch of sky over and over.

I brought the birds in close enough to read the numbers – 326 – on the side, two meters forward of the engine, then I waited.

As it came around for another pass, I launched that flock of Starlings as fast as they could fly toward the numbers.

Fifty meters out, I knew I had misjudged the speed. I would miss my aim-point and hit further back on the fuselage.

Twenty-five meters out, I didn’t know if I would hit it at all. I pushed the birds faster, tensing every muscle in my body and making my shoulder scream out in pain.

A second later, my display went black.

I ripped the glasses off and clawed my way to the mouth of the cave. The underwater voices surrounded me again, but I pushed past them, fixing my eyes on the sky outside.

At first, I thought I was willing the falling trail of light into existence, but as it fell and grew more intense, I knew it was the real thing. The Scorpion careened into the desert floor, exploding in a glorious orange fireball.

I closed my eyes and sat down on the rocks. As the sound of the explosion reached us, I felt bodies jostling me, trying to get a better view of the burning aircraft.

I stayed there for a few minutes, hearing only my throbbing heartbeat and kicking myself for putting the team in such danger.

Never again.

Chapter One

Everyone will get this story wrong, but that’s by design.

I’m writing it down now in the hope that long after I’m dead, historians will find it and decide it’s worth their time. There might even be an award or two waiting for whoever decides to take a closer look. I promise I haven’t deliberately lied or left anything out to make myself look better. Everything is how I remember it, with a few modifications.

I’m also telling this story because I don’t want to be associated with those people on Earth who hate the Prosties and want to lock them up and send them all home. I can’t stop them from thinking the way they do, but I am most definitely not on their side.

This might sound strange coming from someone who has killed more Prosties than anyone else in the universe, but everything I did had a purpose. I had rules. I killed Prosties for a reason.

This was a war, as real and serious as any of the wars humans have engaged in throughout the years. It didn’t look like a war because the Prosties prosecuted their side in an unusual way. They had their rules, too, taken right out of their holy book, the Heka. I knew what would make them stop. Lots of people did, but their demands were impossible to meet.

And the way I prosecuted my side? It would make military theorists pull out their hair. For them, the goal of warfare is the same as it ever was: kill as many of the enemy as necessary to make those still alive bend to your will.

That wasn’t my goal. Not at all.

This is the final reason I’m telling this story. I want people to know there are other ways to win a war. According to Clausewitz, to achieve victory, we must mass our forces at the enemy’s military center of gravity… blah, blah, blah. He’s wrong. He’s a dinosaur. The Prosties’ center of gravity has nothing to do with their military, and the same goes for every civilization in existence today.

‘Prosties’ was my wife’s word for them, by the way. I didn’t make it up. And before you accuse me of dehumanizing an entire race of people, have you heard what they call us? I won’t repeat it, but it’s the only word she used for earthlings well into her twenties. She was born to a Prosledite family on Geb that prayed for hours a day. After we met, she practiced her English on me and couldn’t quite pronounce the word. What came out sounded like Prosties. I laughed, and it stuck.

She signed on to the operation. We were partners. When we weren’t on a mission, we treated each other as equals, which was not how she was treated by her family or any other true believer on Geb. To them, she and the millions of other anti-religious people in the galaxy were lesser forms of life.

They learned this lesson the old-fashioned way: from the Prostie public education system. The same system that taught them their God would one day rule the universe, which sounds grandiose until you realize we only know of two planets containing human life – Earth and Geb.

I know what you’re thinking: are Prosties still human? I’m no biologist, so I don’t know the answer, but I know Prosties have evolved differently in the many hundreds of years since they migrated to a planet with 13% more gravity than Earth. If biology wasn’t so politicized, we might know the real answer, but right now, Prostie scientists say one thing, and some Earth-based scientists say another.

But I’m digressing now, and I have a story to tell, one I should start at the beginning. Not the when-I-was-born beginning. No one cares when I was potty trained or lost my first tooth.

The real story starts the day I lost my parents.

***

I was out of school by then but wasn’t doing much with my life. My father tried to push me into his profession – robotics – but I didn’t want to hold his hand while he helped me climb the ladder. I wanted to choose a path of my own.

The only problem? I no idea what path to choose.

I enjoyed sports, both the virtual kind and the open-air kind. But, because my physical gifts land, to put it kindly, on the upslope of a normal distribution curve, I knew I didn’t have a future in it.

Music was out. My early attempts to sing or play an instrument were embarrassing. I tried my hand at storytelling, but even I found the tales told by AI more enjoyable. I hope this attempt to tell a true story will be different, but I’m not holding my breath. You’re forgiven, in advance, for falling asleep in the next few chapters.

I had a small group of similarly listless friends. We had everything a person could ask for: food, entertainment, time, and the freedom to do whatever we wanted. I don’t think any of us felt we could consume for the rest of our lives. I knew I had to start producing at some point but did not think that point would come as suddenly as it did.

My mom had been planning their trip to Cuba for months. She was never a fan of winters in Winnipeg and was forever trying to convince Dad to fly south for a vacation. He would use work as an excuse to say no, and maybe that was true, but I think he was more of a homebody. Mom was tenacious, though, and eventually wore him down. After he said yes, she hogged the VR room taking virtual tours and planning their visit down to the minute.

She asked if I wanted to come along, but I couldn’t understand the attraction. Turn up the heat, and VR is just like being there. Better. You can sleep in your own bed at night.

Besides, I don’t like to fly.

I know what you’re thinking: why would someone who hates flying agree to spend a year on a spacecraft traveling to another planet? The answer is: when you finally know what you want to accomplish with your life, the things you’re willing to do to achieve it can be astounding.

Sometimes, when I think back on it, my mind tries to trick me into believing some sort of divine intervention stopped me from getting on the plane with them because if I had, I never would have made it to Geb. Except, I know that’s not true. I didn’t have a premonition. I didn’t hear voices. I was lazy and didn’t want to go.

There were four Prosties on the flight. Two men and two women. They subdued the crew halfway to Cuba and took control of the aircraft. They streamed the rest of the flight live. A few million people saw it before the government turned it off, but I wasn’t one of them. I was in the middle of playing a VR game with my friends.

I did see it later. All of it.

For over an hour, the Prosties read from a prepared script calling on all Earthlings to covert, detailing how the Earth rightfully belonged to them and predicting that one day their God would hold dominion over all life in the universe. You can probably still find it in an archive somewhere if you want to hear it, but trust me, that’s what they said.

When the speech was over, they executed the passengers, one by one.

Slit their throats.

Two hundred eighty-seven people.

It took a long time.

When they pulled my mother out of her seat, I couldn’t stand to watch her die, so I focused on my father’s face instead. He looked helpless. I think I know what was going through his mind. He wanted to fight, to protect his wife, but the Prosties were too strong. When you’re born on a planet with more gravity than Earth, you can’t help but be stronger. It’s not their fault.

But my father didn’t fight. He shut down. I don’t know if he thought about me at that moment, but I hope he found it ironic that something good finally came from my indolence.

No one will ever know what he was thinking. The Prosties didn’t give him any last words. They sliced his throat open, threw him on top of my mother, and moved on.

Once they had murdered all the passengers, they turned off the broadcast and crashed the plane into an amusement park in Florida. Forty-two more people died on the ground. There were reports of parachutes in the sky shortly before the crash, but a search turned up nothing, and no one could definitively say the attackers went down with the plane.

What remained of my parents returned to Winnipeg a few weeks later in two small boxes. My grandparents took care of the arrangements. As an only child, I got the house and the bank account and my mother’s knick-knacks and all of my father’s robotic junk.

I walked around the house for days afterward, thinking of nothing except my father’s impotent face. I couldn’t help him any more than he could help my mother. I know that’s when I decided to join the DF, although it’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment. One morning I woke up, and it was the null hypothesis. I spent the rest of the week until I signed the papers trying to talk myself out of it.

This is a point I don’t want anyone to misunderstand. Revenge was not my sole motivation. I didn’t just want an eye for an eye. It wasn’t that simple. I won’t deny it played a part, but the main reason I joined was the vain hope I could prevent other children from being orphaned like I was. If I had known then what I know now, I would have looked for another way, but like most everyone else, I believed the DF was interested in protecting people from Prostie attacks. It wasn’t until months later that I figured out defending the planet was way down their list of priorities.

The evening after I signed the papers, I told my grandparents what I’d done. They weren’t shocked. My Grandmother silently nodded her head, and my Grandfather actually looked proud and said, “It will be a good experience for you, son. It’ll build character.”

Looking back, I guess it did build character, but probably not in the way he envisioned.

***

I reported to the DF campus in Quebec City one month to the day after my parents were murdered.

For the first forty-eight hours, bots shepherded me from one waiting room to another, where other bots tested my DNA and blood. Eventually, I stepped up to being shepherded from classroom to classroom, where bots delivered hours of mind-numbing administrative training and mandatory proficiency tests.

A quick word about bots: you’re probably used to seeing them come in all shapes and sizes and genders and colors. I know I was. My dad worked on every conceivable kind of bot, and no two were ever exactly the same. People personalize them. Make them their own.

Not the DF. Their bots were identical. Every single one. It was bizarre.

They all looked androgynous. It was impossible to guess if they were male or female. Short, straight, light-black hair framed every one of their thin, angular faces. Their skin tone was a pleasing mocha. Their nose was slightly upturned and set between narrow eyes. They didn’t have names. They had numbers like DF1015 or DF2129. If you asked one — and I did — why they were all the same, they’d tell you they were designed to be a composite of every human on the planet. The DF prioritizes inclusion and equity even in bots. A noble goal, perhaps, but it didn’t make them any less weird to look at — kind of human and inhuman at the same time.

I know some people would rather interact with bots, but I’m not one of them, no matter what they look like. I grew up with their inner workings scattered all over the house. I think that might take the bloom off anyone’s bot rose, but I could be wrong.

At the end of the second day, I finally ended up in front of a human. The plaque on his door read “Placement Specialist,” and he introduced himself as Ming. He was taller than average and thin, painfully thin. He spent a few minutes looking through my file, nodding and furrowing his protruding brow, before removing his dark, horned-rimmed glasses and looking at me.

“Mr. Lyon. May I call you Daniel?”

“Sure.”

“Daniel, why did you join the Defense Force?”

“I want to protect and serve humankind around the globe to the best of my abilities.” I got this bit from a presentation the bots gave the day before and regurgitated it without thinking.

“A textbook answer, but it doesn’t solve my current dilemma. Let me try again. What did you think you would do after you joined?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “All those tests I took, don’t they say I’m qualified for something?”

“They do. The problem is your, hmm, physical gifts don’t match your intellectual gifts.”

“I’m too small.”

“If I were looking at your file without regard to your height or weight, I would place you on a leadership track. I suspect your mediocre marks at school and what appears to be a general motivational malaise result from not having a purpose or direction in life. Your parents’ death seems to have shocked you into action.”

“Spare me the analysis. What does my size have to do with being a leader?”

“It would be inappropriate to put you in charge of people who can do things, physically, that you cannot. The equipment they use, the loads they carry, it’s too much for your body, even with—”

“I get it. Stop telling me what I can’t do.”

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to offend–”

“Don’t.” I put my hand up. “I’ve heard it all. The only way you can offend me is if you keep talking about things I can’t do. Keep it up, and I’ll hop off this chair, march out of the room, and tell the first officer I see you made marginalizing comments about my dwarfism. Got it?”

Ming nodded.

“Good. Now, you can’t turn me away, by law, so let’s dive into what I can do for the Defense Force.”

Ming adjusted himself in his seat, his face red with embarrassment. I must admit, I always enjoy the moment when people, trying to signal their virtue to me, realize that I really and truly don’t give a shit. I’m a dwarf, but I’m not a victim. Treat me like everyone else, and let’s get on with our lives.

“I do have an idea you might find interesting,” Ming said softly, “especially due to your father’s background. We’re bringing back a unique drone program that was scrapped many years ago. How would you feel about becoming an intelligence collector?”

“What does that mean?”

“It means you would work in a VR environment controlling a flock of drones designed to look and act like real birds.”

“Can’t AI do that? Why do you need a human?”

“Daniel, I’m in the unfortunate position of placing people into jobs I sometimes don’t fully understand.”

“If I don’t want to fly birds, what other options do I have?”

Ming sucked in air through his teeth. “There are plenty of administrative and logistical desk jobs for which you qualify, but if this conversation is any indication, I don’t think you would last long.”

He was right. I took the drone assignment and, within a few days, was on a flight to Fort McMaster, in the middle of the California desert.

***

The name – Fort McMaster – should have been my first clue this would not be some cushy DF assignment. It was the only facility on the long list called a Fort, the centuries-old moniker for frontier military bases. The DF has a Campus in London. They have Estates in Puerto Rico and Fiji. Their Fort was in the middle of nowhere.

And it was cold! I assumed California would be much warmer than Canada in January, but I was very wrong. I immediately regretted leaving my thermal clothes at home and was forced to order more when I arrived.

Why? The clothing shop on this Fort didn’t carry my size.

The accommodations left a lot to be desired. I even had a roommate! Back then, one of the DF marketing themes was the ‘luxurious living spaces’ available to recruits, but that didn’t apply here. I should have read the fine print.

It may not have been luxurious, but it was functional. There were two bedrooms, two bathrooms (thank God), a kitchen, living and dining room, a VR room, and a middling patio with a fantastic view of the lifeless, red, rocky hill behind the house. I skipped the view, parked myself in the VR room, and turned up the heater.

I had the place to myself for a day until Todd showed up. He stumbled in late the night before class started, dropped his bags in the empty bedroom, fixed himself a drink, and came into the VR room with me. We clicked immediately. He said nothing that night, or at any point during the time we lived together, about my size. To him, I was just another person.

Later on, as he was leaving, he told me what happened the day he arrived. The DF put him through twelve hours of inclusion and equity training before allowing him to set foot inside the house.

“It was such bullshit,” he said. “My sister lost her leg in an accident when she was five, and the thing she hated most was the pity she got when people found out. I didn’t do a single damn thing they told me in those briefings. I did the opposite. I treated you like I wanted you to treat me, just like one of the guys.”

I miss Todd. We stayed up that first night drinking and talking and didn’t go to bed until a few hours before class.

It’s a shame he washed out of training when he did. I could have used him on Geb.

****

Photo by GregMontani (Pixabay)

Comments

Leave a Reply