“And some of us would die – so other men can stand up on their feet like men. A great many are going to die for that. They have in the past. They will a hundred years from now – two hundred. God grant there will always be men good enough.”

Editor’s Note: Click here for Part 1, here for Part 2, and here for Part 3 in this ongoing series on the best books for boys.

Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes is an overtly moralistic tale, and an unabashed, old-fashioned ode to the patriotism and spirit of the founding generation. It was written in the afterglow of “the Greatest Generation’s” victory in WWII. Its protagonist begins the story as a uniquely talented and bright silversmith’s apprentice. Johnny was only too aware of his best qualities – which in turn brought out his worst. He lorded over and bullied the other apprentices, especially the older but duller Dove. The blowback was disastrous – literally crippling – and changed the course of a life Johnny had well planned.

He could not say he had not been forewarned. The silversmith was in the pious habit of requiring the boys to read aloud selected verses of scripture, custom designed to point out to each apprentice his own shortcomings. Dove, for example, was required to read admonitions against sloth in Proverbs 6:6: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard, consider her ways and be wise,” (though the silversmith himself could have drawn a lesson therefrom). In addition to the clichéd (even then) “Pride goeth before a fall…” Johnny was made to recite Leviticus 26:19:

“And I will break the pride of your power; and I will make your heaven as iron, and your earth as brass.”

A sky of iron does not rain, and earth with the hardness of brass yields up neither fruit nor grain. So it is also that when false pride is broken and not replaced by devotion to a cause beyond oneself, a life produces nothing. The emptiness is keenly felt by Johnny, for happiness is not to be aimed at directly – it is but a by-product of a life well-lived.

It takes time for Johnny to absorb this. Even after his injury, Johnny’s mouth continues to gallop on ahead of his brain, worsening his situation in life. Then he encounters Rab, an apprentice for the Boston Observer, a Whig periodical. Rab is a static character – so without flaw or excess as to be allegorical. Rab was “self-contained…. He owned himself.” Rather than directly criticize Johnny for his mouthiness, Rab simply asks what he hoped to accomplish by it: “Why do you go out of your way to make bad feeling?” Johnny has no reasoned answer.

Finally absorbing Rab’s lessons – taught more by example than words – Johnny holds his tongue when a servant girl accidentally throws dishwater on him. She profusely apologizes, and in offering to help clean him up brings Johnny face-to-face with her master; the notorious Whig rabble-rouser Samuel Adams. Johnny is eventually allowed into the inner sanctum of the secretive Sons of Liberty, and directly participates in such seminal events as the Boston Tea Party.

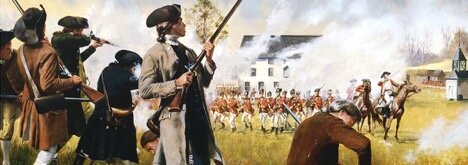

As armed conflict approaches, Johnny encounters British soldiers – both officers and enlisted – and sees in some of them qualities such as honor, courage and kindness. With solemnity, Johnny realizes there will not be cardboard cut-out villains on the other side of the field when war comes, but men and boys much like himself, who will have been placed opposite to him upon the field simply by life’s circumstances. He also woefully notes how well-trained they are, and how unlike his compatriots they have dreaded bayonets in abundance.

Johnny finds himself at the center of the “one if by land and two if by sea” saga, gathering the crucial intelligence alerting the countryside to the British regulars’ plan of march. Rab’s ancestral home is in Lexington, though, and so he leaves ahead of all that to join up with his town’s militia, and it is upon that town’s green that Rab gives his life for a country conceived but not yet born.

As he lay dying Rab gives his musket to Johnny. Dr. Warren – the famed Boston surgeon and chief of intelligence – later sees Johnny handling it, and for the first time he gets a good look at Johnny’s crippled hand. He tells him that it is mere scar tissue interfering with its use, and he can do something about that, if Johnny is willing. Dr. Warren can’t promise Johnny will ever do fine silver work again, but it will be good enough to hold that gun.

***

David Churchill Barrow is a regular Liberty Island contributor and along with his wife, MaryLu Barrow, is the author of the young adult novella Silver and Lead.

Comments