“We will go three days’ journey into the wilderness, and sacrifice to the LORD our God, as he has commanded us.” — Exodus 8:27

Color Sergeant Edmund Findlay Churchill, Company E, 18th Massachusetts, 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, V Corps, Army of the Potomac, was wondering why the hell the withdrawal from the battle lines had to be at 9:00 that night.He was tired – more bone weary than he’d been his whole life; and the last few years had been some life.It’s not like the march would be any big military secret.Everybody, up to and including the Johnnies, knew that they always pulled back behind some river to lick their wounds after taking a beating like that.

His older brother Frederick, who had enlisted in the same regiment a year before he did, had been killed at Second Bull Run. Good name for that battle — it was the name of the river the army had skedaddled to get behind the first time Lee showed them “what for.” Edmund got his first taste of it against that terrible damned stonewall along Marye’s Heights above Fredericksburg.

Back home, a sturdy New England stonewall was such a peaceful, neighborly and handsome thing that it could be the pride of an old Yankee’s eye.But if stones themselves could be evil, the smoking, dirty, jagged line of rocks on that ridge seemed to mock God himself.He’d seen the last of the color guard go down, so he ran up, secured the national flag, and got it safely off the field. That was the first time he’d heard that curious buzzing sound, like bees pouring out of a disturbed hive; the sound of Minie balls whizzing past your head.

They’d decorated him for that, and made him a permanent member of the color guard, but what difference did it make?Back across the Rappahannock they went, what was left of them.His twin brother Isaiah, who had enlisted with him, got real sick at Fredericksburg.Last letter Edmund got from home said Isaiah was getting better slowly.He was lucky – more men were dying of sickness in the lines than from shot and shell. They’d called Antietam and Gettysburg victories, but he’d seen — and smelled — the cornfield at one and the wheat field at the other when the shooting stopped.

Is “victory” supposed to make you sick to your stomach? Isn’t “victory” supposed to mean the other side quits? Well, they might move around some, but Lee and his Rebs NEVER QUIT. Both times they’d just marched unmolested right back into Ol’ Virginny, to rest up and get ready for the next round of bloodletting. This last round, just about over now except for some skirmishers popping away at each other, seemed more than he could bear.

Three days before, V Corps had forded the Rapidan and marched down the Germanna Pike Road, through this horrible scrub on either side that was passable for neither man nor beast.Next they were ordered to turn right on the Orange Courthouse Turnpike, to swat away some nosy Reb brigade paralleling their line of march.Only it wasn’t a brigade.It was “Old Baldy” Ewell’s entire bloody Confederate II corps.

The fight that broke out in the thick brush on both sides of that turnpike was the biggest bunch of bushwhacking Edmund had seen in two long years of war. Hell, you couldn’t even SEE the Johnnies until the fire of their muskets flared out a yard in front of your face. It was also mighty disconcerting in the quieter moments to hear another big fight break out on a parallel road a couple of miles to the southeast. If that should go badly, they’d be flanked on their left, and in a bad fix for sure.

Then the underbrush caught fire. There were wounded boys out there they couldn’t reach. That screaming… Edmund knew then and there he’d wake up in the middle of the night years later hearing that high-pitched screaming. Sometimes a shot would end the sound, and they knew some poor boy had gone to his maker — by his own hand. For two days it went on, until both sides dug in, exhausted, and just about where they’d started. On the morning of the third day orders came down to move out that night as quiet as they could.

Once it dawned on him that it was mostly over, at least for the time being, Edmund had this strange, almost overwhelming longing to go to church. He wasn’t a particularly religious man – not like those fire-belching Boston abolitionists he’d heard back home.Oh, he believed in their cause and all — he’d answered it; and there was of course this little matter of the Union he’d been raised to love being torn in pieces.There just seem to be something … what exactly was it? off-putting? unseemly? … about going around wearing your religion like a top hat.

He couldn’t put his finger on it, but he knew “Swamp Yankees” like him had a different outlook on matters of the spirit than some of these fancy Boston Brahmins, who always seemed like they were looking down their noses at something or somebody. Maybe it was because he was a descendant of those luckless Pilgrims whose Mayflower landed by accident not far from where he grew up. “They were NOT Puritans, dammit!” he would often tell folks who made that common mistake. “They were Separatists… All they wanted was to mind their own business, and for you to mind yours.”

It wasn’t that God was hard to seek out on a battlefield. Any man who doesn’t start praying when that Rebel yell echoes through the woods is either deaf or already dead. He’d even worked out his own little liturgy that he shared with the younger lads in the color guard, to soothe their nerves — and his. As they formed ranks and the lads loaded their Springfields, they would recite the 23rd Psalm together softly.

“The LORD is my shhhepherd…” they’d say together, as they bit into the paper cartridges and he uncased the colors.

“I shall not want…” The boys put the powder down their barrels, while he and the other color-bearer placed the flags in the carriers strapped to their bellies.

“He maketh me to lie down in green pastures…” they whispered, as they seated and rammed down their Minie balls, and he dressed their line.

They were a great big fat target with those huge flags sticking up like that, and the lads couldn’t even shoot back unless the colors were in immediate danger.No, God didn’t seem all that far away when such was the task at hand.

He wanted to go to church – his church — in his hometown, because he remembered how CLEAN Sunday mornings were, especially in late spring.He’d wash up, put on his best go-to-meetin’ shirt and brushed suit, and ride in a buggy that had been polished the day before to that little white Congregational church across from the town green, where they’d sit in their family pew, everything bright with the morning sun coming in through the tall windows.

May in Massachusetts was all fresh, cool air and the smell of lilacs in bloom. Here in Virginia, they were hot and sweating, even at night; and he’d never felt more filthy in his life – inside and out. When they marched in two days ago the ground was strewn with equipment and extra pieces of this and that left behind by soldiers too hot and too tired to carry any nonessentials one step more. Now along with that litter was the flesh and blood of over 27,000 dead and wounded men, blue and grey, and over it all the horrible pall of acrid smoke. Yet for all that, Lee was still out there; planning his next move.

“Ed-MUND??? Oh ED-mund!!!”That’s how Henry Wright, the Company 1st Sergeant, always called for him.He was from the same sleepy little town, and he’d promised Edmund’s Ma that he’d look out for him, especially after they’d lost Frederick.This slightly irritated Edmund, since Henry was only a year older; but even a year out here counted for a lot.It was dark by then, and they’d just finished their supper of salt pork and fried hardtack mixed with water and fat, just to make the tooth-dulling crackers edible.

“Help me get these delicate little children on their feet and in some semblance of good order, would you?”

“Where we goin’ anyhow?”

“Back up that road a piece. But let’s try… just maybe… not to look so raggedy-assed? There’s a tavern up there a ways, and all the big brass is headquartered there. A regular West Point alumni reunion they got goin’. Bunch of geniuses… I’ll tell ya, if they don’t get us all lost in these woods we’ll be damn lucky.”

“A tavern, huh?”

“Don’t get any notions… Water is all you’re getting, just be grateful if you can find some that’s clean.”

Edmund started pushing the boys into as straight a line as he was likely to get. Henry’s crack about West Point made him remember something in a letter he’d gotten about cousin James, who’d been wounded in both legs a couple years ago at a place called Fort Donelson. James was healing up all right – he’d walk again – and he sure didn’t hold any grudge against his commander for getting him shot. He wrote home that their general had laid siege to the fort, and that the Rebs inside were commanded by his old pal from West Point. So they figured he’d let ’em out easy, right? Wrong… When his old friend asked for terms, this is what he got:

“No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.”

Oh boy — now that was a hard case talking. After a while, this fellow seemed like the only Yankee general that hadn’t got his ass whipped by the Johnnies, so Lincoln put him in charge of the whole show.

“Hey, Henry! That new general up yonder somewheres?”

“Ayuh … that’s the word.”

They marched and then they stopped … and then they marched and then they stopped. It seemed like they were only going a few hundred yards each time, and Edmund’s feet alternated between pain and numbness. As they approached an intersection that was well lit with campfires and pine torches, Henry had them all stop and make room to one side. Riders were approaching, and with all the fuss and the staff flags it was clear it wasn’t just some lost cavalry patrol.

Edmund wiped his blurry eyes and tried to focus on the rider in the middle of the group, on a large bay. The man was leaning way over to one side, talking to the officer riding next to him and pointing down the road. It struck Edmund how at ease he seemed in that saddle — like the horse was just a natural part of him. Aside from that he looked like a nobody. He wasn’t very tall, and that blouse looked like he’d borrowed it from the soldier who cooked his breakfast that morning; no braids, no sash, and almost no buttons.

“That’s HIM???” Edmund asked Henry.

“Ayuh …”

“Don’t look like much …”

“Nope, he don’t.”

The riders passed just a few feet away, so close he could finally see the three stars on the epaulettes that seemed like they were the only things marking this man for what he was.Then Edmund began to notice other, more subtle things about him.The slouch hat was pulled down low, as if it hadn’t been moved since it had shaded his eyes that morning as he searched for signs of enemy movement.The large, lit cigar that went quickly right back between his teeth as soon as he finished pointing with it.The leather gauntlets were worn; the boots were muddy.A short beard covered most of his face.

This man obviously had no time for grooming fancy side whiskers or even a regular shave; and his narrow eyes sloped down at the sides, giving him the sad but determined look of an Old Testament prophet. That was it, Edmund thought. There was something Biblical about his look. What was that verse? Something about flint. Oh yes — now he remembered. It was somewhere in Isaiah: “Therefore have I set my face like a flint…”

Edmund didn’t know why, but looking into that face affected him like a hot cup of strong coffee. His feet didn’t seem to hurt so much anymore. He resumed the march, not paying much attention now to what time it was, or where he was headed.

An hour or so later Edmund saw more lights up ahead as they approached another intersection, and he could hear what sounded like cheering from at least a hundred throats. He took a few fast steps to catch up to Henry, who had been going up and down the lines trying to keep things moving.

“What’s THAT all about? Don’t those boneheads know we’re not supposed to be attractin’ attention? There’s bound to be a Reb cavalry patrol out there someplace. Who are that bunch?”

“II Corps… Hancock’s boys… They’re cheerin’ that new general that passed us back there. Even some of the wounded got up and lined the road for him. Damnedest thing I ever saw.”

“Why? What’d he do that’s so God-awful spectacular?”

“It’s not what he’s done; it’s what he’s doing right now.”

“And just what might that be?”

“You are as dull as your plow, farm boy. What direction we headed in?”

“How the hell should I know?”

“Didn’t the escaped contraband from around these parts teach you nothin’? Where’s the drinkin’ gourd?”

Edmund looked wearily straight up at the night sky for the little dipper.

“Can’t see it,” he mumbled.

“Over behind your left shoulder, stupid. We’re headed SOUTH.”

Edmund turned that over in his mind. Let’s see … the Rapidan was to the north; that’s where they had come from. The Rappahannock was due east. Couldn’t think of a river to the south to hide behind. There WAS something else to the south — or more particularly somebody. By God, they were going after LEE.

Cousin James was right. This little “nobody” — this Grant fellow — he WAS worth writing home about. He’d figured out the simple, plain truth that the road home for all the boys was straight through Lee and his army, wherever they might be. Edmund knew Lee was finished as of that night. Grant, on the other hand, was just getting started. That beautiful little white church popped into his mind again, along with something from Ecclesiastes:

“Better is the end of a thing than the beginning thereof: and the patient in spirit is better than the proud in spirit.”

Edmund could almost hear the spring peepers calling him, and hornpout jumping, in the swampy brook behind the farm … could almost smell the bread in Ma’s Dutch oven. Home again soon, Lord willing, and this time for good.

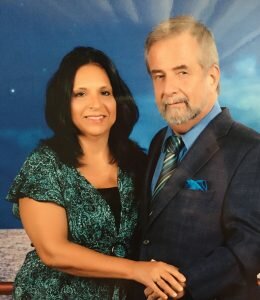

Author’s Note: Edmund Findlay Churchill was a family cousin who grew up in the same sleepy little town as the author, in a house across the brook from the farm where he was raised. Every Sunday he sat in the same pew in the same church that Edmund had a hundred years or so before.

Comments