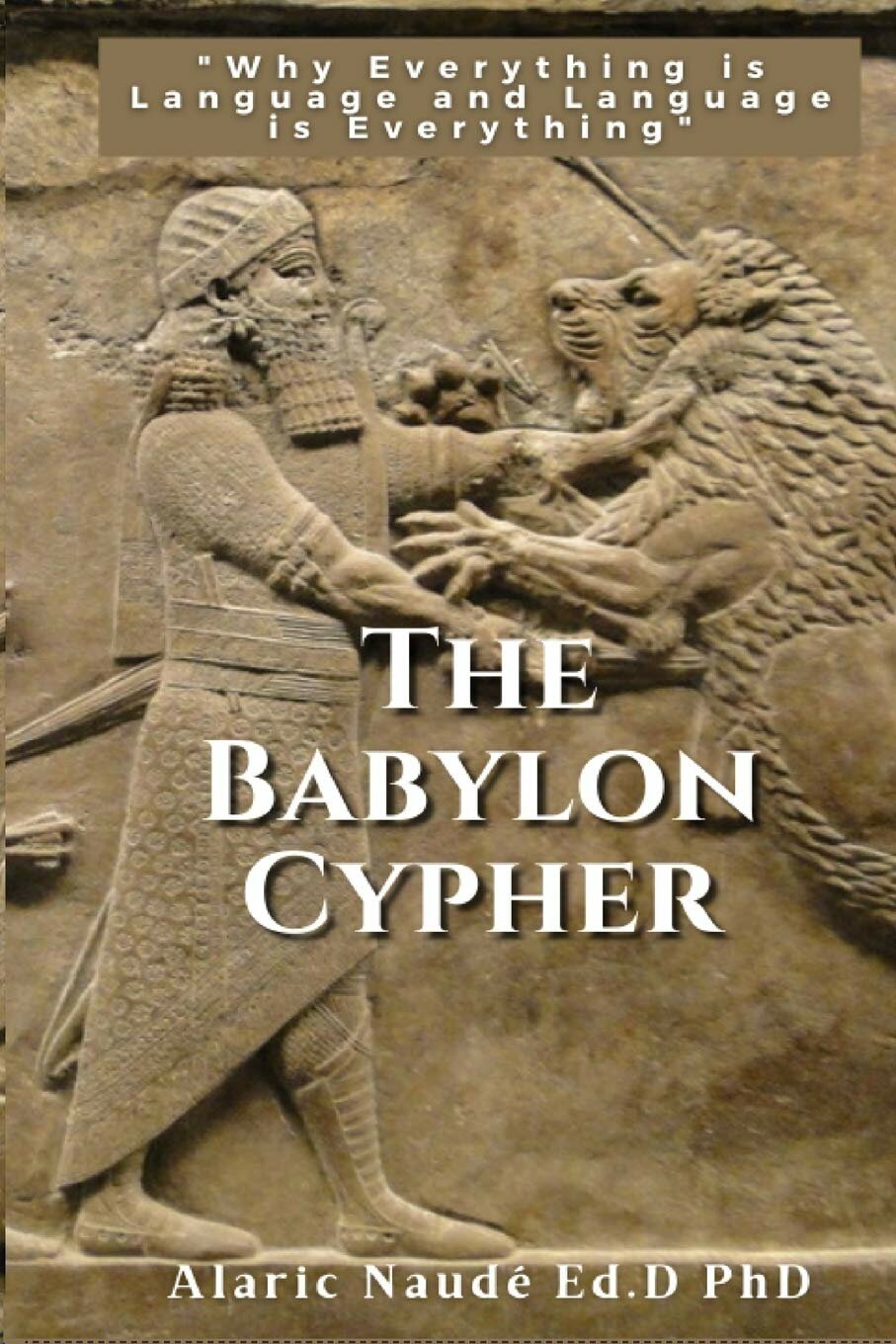

I first got to know Alaric Naudé well when we had a discussion regarding Sapir-Whorf theory, something I discussed in my article “Books You Didn’t Realize Represented the Sapir-Whorf Theory”. Alaric Naudé is an expert on Asian languages. He’s also the Head Professor of English Department at Suwon Science College in South Korea. I interviewed him after his first non-fiction book The Babylon Cypher: Why Everything Is Language and Language Is Everything came out.

Tamara Wilhite: I know you’re fluent in Korean. What other languages do you speak?

Alaric Naudé: Well, I am an ethnic Boer so I speak Afrikaans and I also understand Dutch and speak it with a colloquial heavy accent. I grew up in Kwa-Zulu Natal which is part of the Zulu Kingdom, growing up all my friends spoke Zulu so I did too but unfortunately I have lost a lot due to disuse. Learning languages is an addictive pastime. When I immigrated to Australia I fell in love with Mandarin and Cantonese, my Mandarin is enough to get me by although I do think my writing is better than my speaking. Due to my volunteer work I have been exposed to Arabic so I speak…broken Arabic….mostly broken.

Tamara Wilhite: We’ve discussed Sapir-Whorf theory elsewhere. Can you explain it for our audience here?

Alaric Naudé: The Sapir-Whorf theory was developed by Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf, it is also called Whorfianism but I do not like that term very much due to the negative connotations that comes with so many of the “isms”. A better way of describing it would be linguistic relativity.

Basically, it states that the cognition of speakers or their view of the world will be shaped by the structure of the language they speak. It is a theory I think deserves more attention because there is a great deal of empirical evidence that supports it. Even the ways that words are constructed show a difference in thinking patterns and many bilingual or multilingual persons’ report “multiple personalities” that change as they speak different languages. This suggests that there is a deep and as yet not fully understood link between the patterns in cognition and the patterns found in language.

There has been some contention over specific examples used to express the workings of Sapir-Whorf theory namely the Hopi language, however, despite criticism the mechanisms claimed by Sapir-Whorf theory can quickly be realized when one attempts to translate concepts that exist in one language but not in the target language. This phenomenon extends even into dialects of the same language, thinking patterns that exist as expressions of both culture and language differ greatly even between English speaking countries.

Tamara Wilhite: You’ve written papers and participated in conferences on neurolinguistics. To what degree do you think altering word choice and censoring language actually affects human thought?

Alaric Naudé: I think word choice is a very important area of manipulation. In every extremist ideology we see a push to redefine words and change meanings to suit a cause. That does not mean that semantic shifts do not happen naturally, they do. It does however typically take at least one generation for changes to take place organically and some languages we see such changes are minimal even over centuries.

The problem is that artificial changes create artificial results, the checks and balances required are not present. We only have to look at Nazi Germany to see how reclassification of language can very rapidly lead to very bad results. Take for example the redefinition of racism as being only a system of power and oppression. This unfortunately exonerates the individual from their personal prejudice towards other races, meaning that it removes both personal accountability and also the ability for self-reflection. This is a very slippery slope when it comes to justifying potentially harmful behavior. It doesn’t matter what the ideology is, if it controls the individual’s understanding of definitions, by extension it controls their very perception of reality.

Tamara Wilhite: And what is your book “The Babylon Cypher: Why Everything Is Language and Language Is Everything” about?

Alaric Naudé: Well in many ways the book is exactly about what we have been discussing, namely language and control. I attempt in layman’s terms to layout the history of language and development of written language and how it holds meaning. It discusses language acquisition in children and the preprogrammed steps that babies go through even at the pre-natal stages where language is being absorbed. Language learning is a process that continues from the womb to the tomb.

I also talk about how languages have been used very early in human history to exert dominance and control thus creating hierarchies but also how languages impact on hierarchies. Propaganda is examined and historical patterns in language engineering is compared with what we see happening now, specifically it debunks ideas put across by Robin DiAngelo and Ibram Kendi by understanding the mechanism behind their writing styles.

Tamara Wilhite: What led you to write the book?

Alaric Naudé: A lot of the contents was from when I was writing my PhD dissertation. I found that there was a distinct pattern in how languages became “prestige” or “vulgar” that is to say, the language forms used by elites and those used by the common people. It started to make me wonder on how far this could be controlled and made me look into the many policies that surround language use.

After discussing these with many academics who shared similar observations and being encouraged by readers of my blog to write a book, I finally thought that I should. Actually, after reading work by Jordan Peterson, Gad Saad, Janice Fiamengo, Christopher Paslay, Erec Smith and many others, I saw very well argued ideas and observations but there was a linguistic element missing that I felt needed to be addressed.

My basic aim is for people to understand how language works, to protect their minds from unwholesome influences that seek to polarize and indoctrinate them especially the strong propaganda we see being put out so unashamedly in the mainstream media. Jordan Peterson has a message in his book “Go clean your room”, my message would be “reflect on why you have a dirty room”.

Tamara Wilhite: Some of your work blurs the line between science and science fiction. Your paper Ghost in the Shell: Discussing the Future of Language Teaching comes to mind.

Alaric Naudé: Science fiction for me has always been an attempt at explaining the possibilities that potentially exist, an exploration of what could be. Sometimes sci-fi makes very accurate predictions, for example the episode of Doctor Who in 1977 called “The Face of Evil” predicted the fake news controversy we have today, the same TV show also predicted smartwatches and people being glued to their Televisions. I have made several predictions concerning how technology will become more central to learning, this corona situation seems to have proven my assumptions to be correct.

However, I do think machines have a very long way to go in understanding the nuance of human language, because so much more is involved than merely the semantics in grammar or vocabulary. I think that whether someone is in the hard sciences or in the social sciences there needs to be some open mindedness for inspiration and a healthy fear of what could go wrong, which comes about in that blurred line between science and science fiction.

Tamara Wilhite: You do a mix of language education and translation. What is the most interesting thing you’ve ever translated?

Alaric Naudé: Interesting question, most translation is really run of the mill stuff like cosmetics or technology or basic tourism information. There are things however that can be very challenging. I was given a job where I was asked to translate extensive information on an area of Korea that was the heartland of the Silla Dynasty which reigned from about 57BC to 935AD. It was an immensely difficult task, many of the words are not found in everyday Korean and many Korean speakers do not even know what the objects being spoken about are. For some words, I had to look at the ancient Hanja that they were taken from to get the meaning of the words then construct an appropriate English equivalent because it simply doesn’t exist in English – or in any other language for that matter.

To illustrate one such word was a “type of ancient ornate lotus shaped interlocking roof tiles”, quite a mouthful but about as close to the original as possible. It is not without irony that this type of unique culturally specific language brings us back to the Sapir-Whorf theory.

Tamara Wilhite: I’m more involved in science fiction, horror, fantasy and technology. Thus I’m more familiar with mainstream cartoons like “Avatar” or the potential reboot of “Battlestar Galactica”. But I’m aware of the cultural underpinning of these works. What anime, cartoons, or books like “The Three Body Problem” would serve as a good introduction of South Korean or other Pacific Rim cultures to the Western audience?

Alaric Naudé: I think a film that is science fiction but that has a very realistic feel is the film “Okja” which is the story of a genetically modified super pig which is given to a farmer. The animal is highly intelligent and becomes the pet of a young Korean girl. At some point the company wants their creation back and is willing to do anything and get rid of anyone in their way to do so.

In Korea, large companies are both loved and feared with the ethical behavior of some being strongly questioned both in the sense of their behavior as well as the technology that they are willing to use. This film sheds light on animal rights and corporate greed but also shows unique glimpses of Korean life especially the countryside and mountains which are truly picturesque and calming. This film follows a more benevolent tone than a similar film, “The Host”, where the unethical behavior of a large company dumping chemicals illegally leads to the creation of a mutated fish-creature that lives in the Han River.

Tamara Wilhite: On the flipside, what are some popular misconceptions about Asian cultures that we have because of the content that has gone mainstream?

Alaric Naudé: Just like Asians develop a very romanticized view of the West through film and media, the same happens for Westerners who develop a romanticized view of Asia. Take for example anime and manga which is called man-hwa in Korean.

Comic books are generally viewed as being for children and not really for adults although this is changing with the advent of Webtoons, which deal with topics that are more of interest to working age people. In Korea being interested in comic books as an adult will get you called an “otaku” which is a nerd or geek but the same won’t happen for webtoons which are popular with everyone from university age students to office workers.

Also because there is a stylized presentation of Westerners in Asian media and film there is the misconception that just coming to Asia as a Westerner will make one highly desirable but this is not the case. Asian cultures deal with social hierarchies and the saving of face so they avoid confrontation which Westerners may confuse with approval.

Personally I think about 50% of what is going on in a story whether it be anime or normal films is being lost on the Western audience merely because of the vast cultural gap. For example, it may be something in the background that is giving additional information such as a bowl of rice with chopsticks stuck in it or other very culturally specific nuance that the translation cannot properly convey.

Tamara Wilhite: We’ve already discussed your first book. What else are you working on?

Alaric Naudé: Ah ha! Spoilers! Well, I have been asked to write a chapter on education in east Asia for a book on global economics, so there’s that. I do have plans in the pipeline for a book on either a concise history of slavery or the gender pay gap.

Something else I am looking at is compiling a book that contains the thoughts of some modern academics or scholars that are taking a more measured approach in their attempts to understand social or scientific phenomena, so that would be a collaborative work.

Tamara Wilhite: Is there anything you’d like to add?

Alaric Naudé: Well, I hope that my book is able to help people in their self-reflection and to take a step back to analyze how much they have already been affected by propaganda without knowing it but also to gain an interest in learning about other cultures and especially learning another language.

Tamara Wilhite: Thank you for speaking with me.

Comments

Leave a Reply