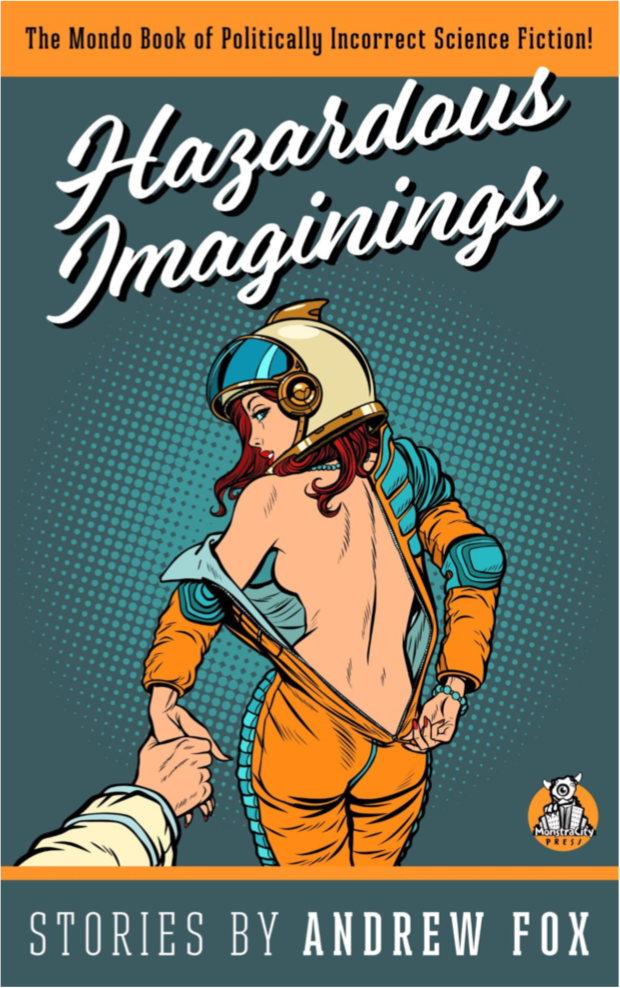

Science fiction and horror author Andrew Fox’s first novel was Fat White Vampire Blues. He’s continued to put out a steady stream of science fiction and fantasy that’s equally edgy and entertaining. For example, he recently released a short story collection titled Hazardous Imaginings: The Mondo Book of Politically Incorrect Science Fiction. And I had the opportunity to interview him.

Tamara Wilhite: Hazardous Imaginings seems to be modeled off of Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions. Is that intentional?

Andrew Fox: Most assuredly. Not long after Harlan died, I watched a documentary on him that had been made pretty late in his life. Watching it and mulling over his career, I thought, “If Dangerous Visions were published today, what kinds of stories would it include?” That got me thinking about the issue of taboos in science fiction, what gatekeepers, editors, and opinion leaders in the field shy away from, discourage, or ignore. What was taboo back in 1967 is not only acceptable in the science fiction field today, it is celebrated and widely published and awarded. Today’s science fictional taboos are viewpoints and ideas that fall outside the progressive bubble that so many of present-day editors and gatekeepers inhabit.

I also remembered, with sadness and resentment, the treatment of my good friend Barry N. Malzberg, an award-winning science fiction writer with a fifty-year-long career whom I’ve admired since I was a teen, by the editors and readers of the Bulletin of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFFWA) in 2013. Barry and his frequent collaborator, fellow award-winner Mike Resnick, had a long-running column in the Bulletin called “The Resnick-Malzberg Dialogues”.

They covered all sorts of topics pertinent to science fiction writers and professionals, from how to best break into the magazines to the worthiness of convention attendance in building a career, often in a semi-comical tone reminiscent of The Odd Couple or Grumpy Old Men. In 2013 they turned in a two-part article on the history of women editors in science fiction, which focused mainly on a handful of obscure but worthy ladies who toiled in the pulp magazines in the 1930s and 1940s. Their “mistake” was to unwittingly stumble over a woke trip-wire by referring to their subjects as “lady editors” and by relating a humorous anecdote from the 1950s that turned on the attractiveness of one of the editors in a swimsuit and how this got some male fans in trouble with their wives.

The gates of Woke Hell were opened, and the two writers were subjected to every sort of online abuse and name-calling for weeks on end. The end result was that their column was cancelled, the Bulletin’s (lady) editor was fired, and the magazine ceased publication for six months while all traces of “bad think” were thoroughly purged.

The wokeness plague in science fiction has only grown more virulent since that episode. Other prominent writers have been publicly defamed for trivial matters, the names of science fiction’s founding fathers and mothers, including John W. Campbell and Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree, Jr., have been yanked off annual awards for perceived transgressions against wokeness, and writers and editors have been physically expelled from conventions where they were serving as guests for daring to question political correctness during discussion panels. No editors outside of Baen Books (which concentrates on military and adventure science fiction and fantasy) will touch material that comes across as politically right of center.

Yet in this time of accelerating technological change and resultant social change, we need a healthy, vigorous, daring, and courageous science fiction, more than ever. Science fiction — unfettered, uncensored science fiction — can serve as our telescope, allowing us to ponder what is coming and prepare. In order for science fiction to serve as an early-warning radar for dangerous technological and social trends, its practitioners cannot wear blinders. We can’t afford the luxury of disregarding a whole swath of potentially invaluable viewpoints.

I originally wanted to call the anthology I’d envisioned Today’s Dangerous Visions. I contacted the Harlan Ellison Estate to ask whether Harlan’s widow, Susan Ellison (who passed away not many months after I tried contacting her), would approve of this and whether she would like to be involved. The Estate is very protective of Harlan’s trademarks, among them the brand “Dangerous Visions”, and they weren’t interested. In fact, they ordered me to cease and desist even mentioning Harlan Ellison and his legacy (“Harlan Ellison” is also a trademark of the Ellison Estate) in crowd-funding appeals to raise money for story royalties.

So I changed my title and went off in my own direction. I gathered a wonderful selection of stories from writers around the world, and I ended up writing so many tales myself that fit the theme that I ended up dividing the envisioned book into two volumes, the first made up of my own stories, and the second of the stories submitted to me.

Tamara Wilhite: I’ve noticed a number of similar science fiction collections like yours such as “Forbidden Thoughts”. What is driving the publication of these anthologies? And what has the demand for them been like?

Andrew Fox: Science fiction has always had more than its share of contrarians. Count me as one of them. There is a long history of contrarian anthologists pushing back against whatever the “in” thing is in science fiction by soliciting stories that break the widely accepted mold. Judith Merril did this with her Year’s Best SF anthology series, of which twelve were published between 1956 and 1968. During the late 1950s, a time when the Campbellian ideal of science fiction as the solving of problems by “the capable man” still held wide sway, Judith was selecting what would now be called slipstream stories, literary fiction with slight fantastical elements by non-genre authors such as Eugène Ionesco, John Steinbeck, Donald Barthelme, and Jorge Luis Borges. She strongly believed that in order to flourish, science fiction had to break out of its genre ghetto and merge with mainstream literature. Both she and Harlan Ellison championed science fiction’s New Wave in the latter half of the 1960s, a movement in both Britain and America that injected the stylistic experimentation of modernist and post-modernist literature into science fiction, focused on “inner space” rather than “outer space”, and expanded the range of themes that could be expressed in science fiction. The New Wave movement was bitterly opposed by science fiction’s more traditionalist editors, writers, and readers, who saw its oftentimes darkly pessimistic and sometimes nihilistic outlook as a decadent betrayal of science fiction’s mission, which in their view was to illustrate how technological advances could solve humanity’s problems and to warn against wrong turns in future technological developments.

Nowadays, to be contrarian or counter-cultural means to be outside the progressive consensus that has swept over much of high and popular culture, the educational establishment, and is now assimilating much of corporate America, even the realm of professional sports. To be contrarian means to be anti-woke, or at least non-woke. I was discussing with a correspondent of mine just recently how, regarding diversity of cultures, practices, sexual preferences, etc., the left has moved on from “live and let live,” an attitude I’m fully in accord with, to trying to enforce not just toleration, which is essential in a multiethnic society like ours, but also affirmation and celebration of their favored flavors of diversity. I think that’s where a lot of the resentment from those not on the left comes from — the sense that they are being pressured and bullied into affirming and celebrating behaviors and qualities they are willing to tolerate in others but are not in favor of for themselves or their families. Progressives can be very aggressive about claiming fresh territories; there’s a lot of truth to Robert Conquest’s Second Law of Politics, “Any organization not explicitly right-wing sooner or later becomes left-wing.” In the science fiction world, we’ve seen the Second Law at work with the science fiction imprints at the major publishing firms, with the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, with the World Science Fiction Convention and their Hugo Awards, and with a wide range of regional science fiction conventions and awards committees. Locus Online, the field’s primary news magazine with a long and storied history, had a Black Lives Matter banner on its home page the last time I looked. The slogan is innocuous and anodyne, but the organization of that name is pernicious in many ways. And besides, what do that slogan and its namesake organization have to do with news of the science fiction world? As Glenn Harlan Reynolds has been known to say, “you will be made to care.” (Mind you, I admire very much was Locus does and loved Charles Brown’s long run as editor there; their people have always been gracious with me, and I have a stack of their old issues in my basement. But I don’t need a daily dose of Black Lives Matters with my science fiction news.)

Most people don’t like being forced to favor, or pretend to favor, things they really don’t favor. They don’t appreciate being called deplorables and thought of as outside the pale of polite society. That’s where the energy for the Sad Puppies uprising came from, and presumably for the Forbidden Thoughts anthology, which involved many of the same participants. I’m referring to a visceral reaction against the progressive science fiction and fantasy that all the “best people”, the genre’s elite tastemakers, praise and promote — “ I say it’s spinach and I say the hell with it!”

My own motivation for putting out the Hazardous Imaginings books goes a bit beyond that. I believe very strongly that we are entering a hazardous era in human history, primarily due to the geometric growth of consumer-grade technologies that give ordinary people powers of creation and destruction formerly limited to national governments, militaries, and large scientific establishments and jealously guarded by them. In order for us to successfully navigate this dangerous era, we need the cognitive habits of the best science fiction, and science fiction needs all hands on deck. We’re handcuffing ourselves if we let a whole contingent of writers self-censor what might prove to be their most illuminating and valuable insights because they fear being exiled from the commercial markets for wrongthink.

That’s a really long answer to the first half of your question. Now I’ll address the second part: what has the demand for these counter-cultural science fiction anthologies been thus far? Not nearly as high as it should be.

This part of my answer probably won’t make me very popular, but I think the conservative and libertarian media outlets need to greatly up their game when it comes to getting the word out regarding projects like these. I’m a regular consumer of a wide variety of right of center news and commentary sites, along with arts and policy sites of all stripes. I’m also pretty much an ideal customer for the anthology Forbidden Thoughts, which featured an all-star lineup of science fiction writers and championed freedom of expression and conscience. Yet I never came across so much as a mention of the book in any of the sites I read several times per week. I only discovered Forbidden Thoughts when I was trying to publicize my crowdfunding campaign for Hazardous Imaginings, when one of the Forbidden Thoughts editors emailed me to tell me he and his group had put out something similar.

This shouldn’t have been the case. I’d need the toes of a centipede to count the number of prominent conservative and libertarian commentators who regularly push the notion that culture is upstream of politics. Well, do you know what is upstream of a whole lot of popular culture? Prose science fiction. Film, television, and gaming science fiction do not generate original science fictional ideas. They borrow them from written science fiction, often science fiction that is fifty years old or older. Media science fiction has already strip-mined much of classic science fiction. Eventually it will catch up with more contemporary works. If conservative and libertarian voices are absent from widely available contemporary prose science fiction, the only science fiction films, streaming series, and interactive video games will be based on progressive fiction.

I am very appreciative of the support Liberty Island has shown my Hazardous Imaginings project, along with Christian Toto of Hollywood in Toto and Sarah Hoyt of Instapundit. But no other conservative or libertarian outlets have shown any interest at all in this landmark pair of volumes, and I’ve sent information and announcements regarding the books to virtually all of them. I’m not an Andy-Come-Lately; I have a nearly twenty-year track record in publishing, both traditional/commercial and indie publishing, and I’ve been writing about free speech and cancel culture issues in science fiction for many years now. The Hazardous Imaginings books contain serious, incisive extrapolative examinations of a number issues near and dear to conservatives’ and libertarians’ hearts, including the societal dangers of intersectionality; environmentalism taken to a horrible extreme; groups involved in extreme competition for top victim status; the pariahdom suffered by any researchers into potential biological and cultural factors contributing to differences in average intelligence levels between groups; and the great hazards of judging governmental social programs by the beauty of their intentions, rather than the reality of their actual results. To the best of my knowledge, my novella in Hazardous Imaginings, “City of a Thousand Names”, is the first work of science fiction to take the concept of intersectionality to its logical, absurd, and eventually murderous extreme.

These books are exactly the sort of cultural products the pundits say we need to see a whole lot more of, aren’t they?

So the big-time conservative and libertarian mouthpieces need to back up their rhetoric with some actual support. Be our cheerleaders! Let our potential audiences know we exist! Help us build a community of readers! Or projects like mine will die on the vine due to a lack of awareness. Conservative and libertarian nonfiction does just fine. The market for non-woke, non-progressive fiction, on the other hand, needs to be nurtured in order to grow. Especially a market for fiction that intends to provide readers with more than simple entertainment, that seeks to explore ideas and extrapolate existing trends in an intellectually serious fashion.

If the big-name pundits with their mighty platforms can’t get behind a project like this, I don’t want to hear them bewailing the reality that culture is upstream of politics ever again.

Tamara Wilhite: Your first novel was Fat White Vampire Blues. What was the inspiration for that?

Andrew Fox: In 1998, I was living in New Orleans, recently divorced and recovering from a badly broken ankle. I’d set aside my writing for almost a year, but I was starting to develop the itch again, wondering what my next project would be. My new girlfriend was a big SF and horror fan, and she loved gossiping with her eccentric landlady. Turned out this landlady went to the same Uptown New Orleans beauty parlor as local celebrity author Anne Rice, and soon my girlfriend was filling my ear with stories of how said author had ballooned to an impressive size.

The image stuck with me. New Orleans, of course, is famous for its food, one of the world’s most calorie-laden cuisines, heavy on the cream sauces. New Orleans regularly contests for the title of America’s Fattest City, most often with Philadelphia, whose Philly cheese steaks can’t hold a candle to our andouille gumbo or fried trout almondine. I reasoned that, if vampires actually “lived” in New Orleans and subsisted on the blood of New Orleanians, they’d be sucking down a stew of cholesterol and fatty lipids with every meal. After a century or so, a New Orleans vampire would look a heck of a lot more like John Goodman than Tom Cruise.

One of my favorite New Orleans novels, and one of the all-time great comic novels, is John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, which features gargantuan Ignatius Reilly getting into a series of misadventures in 1960s New Orleans while fighting a losing battle against the twentieth century, progress, and all forms of “aesthetic abomination.” Confederacy got added to my recipe. My vampire character quickly started taking shape — Jules (named for a favorite overweight coworker) would be a member of New Orleans’ shrinking white working class, left behind during the rush to the suburbs, chained to his old, decaying neighborhood by nostalgia and a genuine love for the central city. Over the long decades, his weight had gradually crept up, until he reached the point where he was too big and slow to chase down victims anymore. Once he hit four hundred pounds, he took up driving a cab, because trapping his victims in the back seat was the only way he could capture a meal. Finally, circumstances force Jules to consider the four-letter word he hates the most: D-I-E-T.

Tamara Wilhite: And how on Earth did you end up writing sequels like Fat White Vampire Otaku?

Andrew Fox: I have a very active imagination. And I love mixing my passions from various genres. That’s how a trio of Japanese super-heroes end up in New Orleans after my version of Hurricane Katrina. They are there as International Red Cross volunteers — my house on the West Bank of New Orleans was about a mile away from the staging area used by the Red Cross and first responders from all over the country after Katrina, and my local coffee shop, P.J.’s, was the first business in the area to reopen. So all the police and EMTs and fire fighters and Red Cross volunteers from all over would crowd in there every morning for their morning cup of joe, and that’s where I did my writing, between chatting up all those folks. I loved that place and that time. Such a fantastic sense of fellowship.

Tamara Wilhite: Would it be fair to say that a lot of your works like “The Good Humor Man / Calorie 3051” are absurdist?

Andrew Fox: I prefer the term “gonzo,” stolen from the late Hunter S. Thompson. A lot of my novels and stories come from the sort of questions you ask yourself while taking a shower or trying to fall back asleep in the middle of the night. My yet unpublished novel The End of Daze, which MonstraCity Press will probably put out in 2021 or 2022, grew out of such a question. Nearly every religious tradition has its own version of eschatology, or end of days times. Although some of these may overlap in certain ways, they can’t all come true. So I asked myself, what would happen if one of those end of days scenarios came to pass? Specifically, what would happen if it were to be the Jewish version? What would Christians and Muslims think? What would the Jews themselves think, with so many American Jews being devoutly secular?

With The Good Humor Man, or, Calorie 3501, the question I asked myself was, what if our Western mania for thinness gets completely out of hand and we find a technological way to thin ourselves to death? I had previously written a short story about a former liposuctionist in the future who is obsessed with recovering a lost relic, the preserved, liposuctioned belly fat of Elvis Presley. I added him into the story, then patterned my plot on that of Ray Bradbury’s classic Fahrenheit 451 (originally a novella called “The Fireman”), except that, instead of having firemen in fire trucks racing around burning up banned books, I’d have Good Humor Men in Good Humor vans racing around burning up banned high-calorie foods.

Tamara Wilhite: You’ve written more serious fantasy, as well. What is Fire on Iron about?

Andrew Fox: When I was a boy, I was fascinated by Civil War ironclads like the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia. I checked out the American Heritage young readers’ book Ironclads of the Civil War so many times from my elementary school library that the librarian called in my mother and asked her to order me my own copy; I still have it on my shelf. Again, I enjoy mixing up things that I love with one another.

I was eating my lunch at the food court near work when an image popped into my head that really stuck with me — Civil War ironclads battling elemental fire demons on some backwoods Southern river. Don’t know where that image came from. My initial bright idea was to write a series of dark fantasies and science fiction novels all having the titles of bad sci-fi B-movies from the 1950s; I figured I’d call this one Navy vs. the Night Monsters. I didn’t stick with that idea for long, which was probably for the best.

Here’s the precis of the plot: Lieutenant Commander August Micholson lost his first ship in reckless battle. Now he’s offered a chance to redeem himself — he can take the ironclad gunboat USS James B. Eads on an undercover mission to destroy a hidden rebel boatyard and prevent the Confederates from building a fleet of ironclads that will dominate the Mississippi. But dangers far more sinister than rebel ironclads await Micholson and his crew. Micholson is faced with a terrible choice: he can risk the fiery immolation of every American, both Union and Confederate, or he can risk his soul by merging it with that of his greatest enemy.

MonstraCity Press will publish the second book in this series, Hellfire and Damnation, in August 2021. There’s also a third book in the series, Fire on the Waters, that will come out after that. Lots and lots of Civil War steampunk dark suspense!

Tamara Wilhite: You had Hazardous Imaginings, The Man Who Would Be Kong and a zombie Sherlock Holmes story, “Watson Has Killed Me, Alas” come out in October, 2020. Do you have anything in progress or coming out soon?

Andrew Fox: I have a very full publishing slate of books coming out from MonstraCity Press over the next year. This December, as I mention above, I’ll be putting out Again, Hazardous Imaginings: More Politically Incorrect Science Fiction, the international anthology that features one of your stories. In February 2021, I’ll be issuing The Bad Luck Spirits’ Social Aid and Pleasure Club, a dark fantasy about a cabal of evil spirits who plot to destroy New Orleans with a Katrina-like hurricane.

In April 2021, the third book in my Fat White Vampire series, Fat White Vampire Otaku, will come out in paperback (it’s been available in ebook form for a few years). For June 2021, MonstraCity Press will publish the fourth book in the Fat White Vampire series, Hunt the Fat White Vampire. In August 2021, I’ll put out the sequel to Fire on Iron, Civil War dark fantasy Hellfire and Damnation.

I’ll probably do another Fat White Vampire book before the end of 2021. Also in 2021, Potomac Press will be putting out a non-fiction book of mine concerning the implications of Promethean technologies, consumer-grade tech that gives ordinary persons the sort of creative and destructive powers once only available to national governments, powerful militaries, or well-funded scientific establishments.

For 2022, I have a number of Hazardous Imaginings-type, politically incorrect novels I’ll be putting out, all of which are guaranteed to set Woke Zombies’ hair on fire. If the first two Hazardous Imaginings story collections do reasonably well, and I very much hope they do, I’ll commission a third book in the series.

Tamara Wilhite: Is there anything you’d like to add?

Andrew Fox: Readers can sign up for my newsletter and receive a free ebook, my Tinseltown fantasy “The Man Who Would Be Kong”, by going to my Story Origin landing page. What a deal!

One last word to any big-name pundits who might be reading this: bang your drums loudly for the Hazardous Imaginings project! It’s what you’ve been asking for for years now! Hazardous Imaginings: The Mondo Book of Politically Incorrect Science Fiction is available in paperback and ebook now, and Again, Hazardous Imaginings: More Politically Incorrect Science Fiction will be out in December and will be available for preorder. They make great Christmas or Hanukkah gifts!

Tamara Wilhite: Thanks for speaking with me

Comments

Leave a Reply