The article, in the September 24 edition of The New York Review of Books, clangs like a false note. I read it once and wondered what its point was? I read it again and wondered what its hook was? The article by long-time New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm begins with her recollection of visits in the spring of 1994 to a speech coach at his apartment on Manhattan’s Lower West Side. So far so King’s Speech. But Malcolm is different from her speech coach’s typical client: an actor cast to play “Prospero, say, or Creon, so that they did not sound as if they came from the Bronx or Akron, Ohio.” She was there to rehearse her part as a witness in a court case.

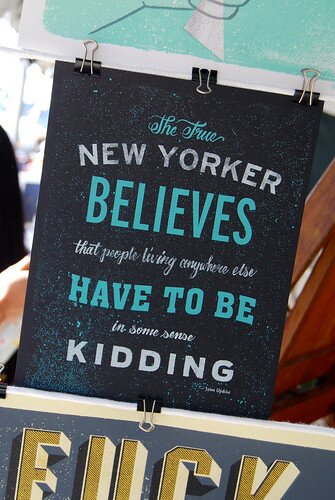

Malcolm had been sued in 1984 for libel by the subject of one her articles. In a decade-long case that included a Supreme Court ruling that held that the case could go to trial by jury, a jury ultimately found for the plaintiff. But in what Malcolm describes as “incredible good fortune” the jury could not agree on damages. A retrial was declared. Malcolm attributes the original verdict to the “very high tone” that she adopted: “I was part of the culture of The New Yorker of the old days—the days of William Shawn’s editorship—when the world outside the wonderful academy we happy few inhabited existed only for us to delight and instruct, never to stoop to persuade or influence in our favor.”

As she describes it, “[the plaintiff’s] lawyer could hardly believe his good fortune. He made mincemeat of me. I fell into every one of his traps. I came across as arrogant, truculent, and incompetent. I was at once above it all and utterly crushed by it.” The job of the speech coach on West 16th Street was to temporarily erase from her “the New Yorker image of the writer as a person who does not go around showing off how great and special he or she is.” It was to make her more attractive to the jury. “A trial jury is like an audience at a play that wants to be entertained,” she writes. “Witnesses, like stage actors, have to play to that audience if their performances were to be convincing.” In a certain way, the task of her speech coach was to take an existing Prospero or Creon and make them sound as if they came from the Bronx, or Akron, Ohio.

Apart from changing the way she dressed it is not entirely clear how Malcolm’s transformation occurred in the second trial, which she won. The single detail she provides is a long monologue that she “performed” on the New Yorker technique of “compression.” She describes how she won by talking over the opposing lawyer’s interruptions. I am not quite sure how this made her more appealing or appear less condescending but apparently it did the trick.

“Compression” incidentally is a literary device where New Yorker writers “compile” an “uninterrupted monologue in which characters made preposterously long speeches in impossibly good English.” Such as?

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind: we are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

Justifying this device, she continues: “Anyone could see that the speech had never taken place as such but was a compilation of what the character had said to the reporter over a period of time.” I actually was shocked by this, having had the naïve idea that what is in quotations in the New Yorker was actually said. I am not surprised that she lost the first trial. But Malcolm dismisses such quaint objections: “Not everyone liked the convention, but no one thought it was deceptive since its artificiality was so blatant.” What kind of argument is this? We are so obviously putting words in your mouth that you must recognize that they are true!

And after this digression on “compression” we reach the end. We learn that the speech coach died—but in 2011. I had thought perhaps this recollection had been prompted by his recent death, but apparently not. She informs us that he, at least, had an “unspoken but evident distaste for the New Yorker posture of indifference to what others think.” She writes that his guidance “took me to unexpected places of self-knowledge and knowledge of life.” But what did she really learn except for how to fool the rubes when it came to the Benjamins? “I relapsed into my usual habits of solitary work and private intimacy.”

Malcolm’s tale is of a Goddess descending to the world of mortals and bringing back to the Elysium—NYRB subscribers, I mean—her account. She had learned to dress differently, talk differently, engage with such base creatures, flatter them on their own terms, and come back to tell the story. It is a fascinating insight into an attitude.

As you from crimes would pardon’d be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

*****

Photo by nick.amoscato

Comments