At times these times require escape. Here again America’s once great institutions fail us. Perhaps it is just a question of personal taste, but I find very little that is produced by the American entertainment industry to be enjoyable. My wife and I have a five-minute veto rule. We each have the right to veto something that we start watching within the first five minutes. Since movies in particular are so formulaic the first five minutes are reliable indicators of the style that will follow. Neither of us like horror, science fiction, or superheroes. That leaves comedy, romantic comedy, and drama. I usually exercise my veto when there is mention of anything scatological, onanistic or crudely sexual. This is for reasons of taste not prudishness. But it rules out pretty much everything produced in those genres these days.

Is there a difference between “escape” and “escapism”? I see it a bit like Paul Bowles’ distinction between tourism and travel, voiced by his character Port Moresby in Sheltering Sky. Port says the tourist hurries back at a set date; the traveler roams. The tourist sees things in terms of his own civilization; the traveler evaluates the civilization he is visiting and then discards what he does not like about his own. There is a snobbism to this definition but that is a matter for another day. It works as a metaphor: the movie “tourist” wants to get away for a while and the movie “traveler” wants to be immersed in a different world. The tourist has a lower bar for suspension of disbelief. The traveler seeks greater complexity. This is not a value judgment. In fact, we have had this debate on this website before, where many of my fellow-writers are huge fans of the Marvel genre. De gustibus non es disputandum.

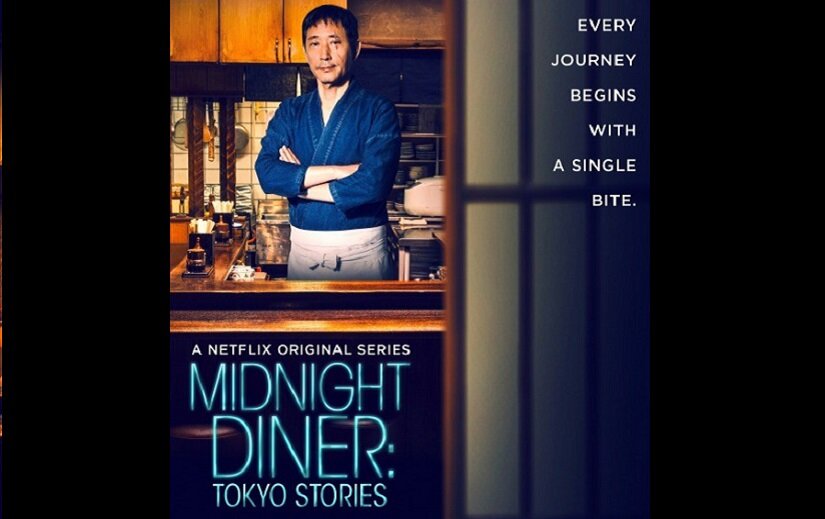

Which brings me to the other night, a frustrating roam through Netflix trying to find something worth watching. An evening laziness that sought something distracting but not annoying. A night of tourist entertainment. Even with that low bar I couldn’t find anything. I tolerated a few shows or movies and had to switch them off. Reluctantly I clicked on “Midnight Diner,” a Japanese show now streaming on Netflix. I wasn’t looking for subtitles or something foreign, but I was out of options. And I was delighted from the beginning.

While a lugubrious Japanese ballad plays, we see the bright-lit midnight streets of Tokyo through the windshield of a car. Then the narrator’s voice:

When people finish their day and hurry home, my day starts. My diner is open from midnight to seven in the morning. They call it “Midnight Diner”. That’s all I have on my menu […]. But I make whatever customers request as long as I have the ingredients for it. That’s my policy. Do I even have customers? More than you would expect.

Each episode is around the 22-minute length of a sitcom. There are some recurring characters but mostly the show focuses on the story of someone who happens to show up in the diner. Based on a Manga series, “Midnight Diner” has the quality of a well-rendered short story, more Cheever than Cheers. The actors are often surprisingly unattractive but endearing. The taciturn owner of the diner, known as cancel-beckoning “Master,” gives advice but has no story of his own.

It is surprising how much is packed into twenty-two minutes of slow-moving action. This is due to how well-rendered the characters are—their psychological complexity. To give one example: a nephew whose father died abuses the generosity of his never-married aunt, who became his guardian. The aunt is an old flame of one of the diner’s regulars. The nephew eventually steals all her money and runs away. A bit later he sends her a necklace for her birthday. Deeply content she shows it off at the diner. Her old flame says she should be embarrassed as the nephew probably used the money he stole from her to buy the necklace. The aunt, who had lived alone most of her life, said that once her nephew started living with her, “I learned that it was a joy to work for someone else for the first time in my life.” It is refreshing to see that sort of psychological depth. For anyone who has tried to write fiction, “Midnight Diner” is a reminder that the simplest effect is the most difficult to achieve.

“Master” works alone in his small kitchen and the camera lingers on the meals he prepares. Like the stories themselves, simple, based on a few ingredients, but given flavor by meticulous craftsmanship. An article about the show on decider.com argued that the show was really about the food: “What I’m saying: come for the decent-enough narratives. But stay for that steaming hot bowl of delicious-looking miso.” I think this is wrong: the food is the metaphor for how the stories were written. At the end of each episode the main protagonist breaks the fourth wall and explains the recipe—and writers should take note.

Comments