Among the multitudes that America used to contain were Whittaker Chambers and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. A few months ago I happened to reread both Chambers’ autobiography Witness and Schlesinger’s Journals 1952-2000 one after the other. These two men are of different generations: Chambers lived from 1901 to 1961 and Schlesinger 1917 to 2007. They are of completely different temperaments, milieus, politics, and tastes. But there are some fascinating overlaps that have some bearing on the difficult passage we are traversing today as a nation. Both were superb writers.

Chambers is most well-known for exposing Alger Hiss, a high-ranking former State Department official and head of the Ford Foundation as a long-time Communist spy. Chambers himself had been a Communist but broke with the movement in the 1930s. His later accusation against Hiss led to two trials and Hiss’s eventual conviction for perjury.

Chambers describes his turn to Communism as a way of addressing what he describes as the crisis of the modern world: “the impact of science and technology upon mankind which, neither socially or morally, has caught up with the problems posed by the impact.” After breaking with Communism Chambers returned to his Quaker roots, seeking shelter from the modern world at his Maryland farm, where he wrote his memoir after the grueling and often humiliating Hiss trials. In a deeply affecting introduction, written in the form of a letter to his children, he describes his role in the titanic struggle between two faiths: Communism and freedom. “Freedom is a need of the soul, and nothing else. It is in striving toward God that the soul strives continually after a condition of freedom.” Communism, he writes, “is the vision of man’s mind displacing God as the creative intelligence of the world.”

This recurring sense of a global and general crisis seems to be animating those behind the current unrest—in the same way that it animated the students of 1968, or those young, troubled idealists like Chambers and Hiss who became Communist in the aftermath of World War I. Animating all three impulses was a critique of America and the question of race. On the latter, at a far more segregated time, Chambers writes a beautiful passage about how his family insisted that their black housekeeper dine with them:

“What we had to give her was not a place at our table. What we had to give her was something that belonged to her by right, but which had been taken from her, and which we were merely giving back. It was her human dignity. Thus, by insisting on acting as Communists must, we found ourselves unwittingly acting as Christians should.”

Schlesinger, a Harvard professor of American history but is better known for having a been a long-time speechwriter for Democratic party leaders and the intellect of the party. He famously defected from Adlai Stevenson to join Kennedy’s 1960 winning presidential campaign and has forever been associated with Camelot. If they were writers for the London Spectator, Chambers would write Low Life Schlesinger the High Life. His journals are littered with dropped names, from Hollywood to politics, literature to international luminaries. He is always at the White House, or the Democratic convention, and everyone is calling him at all hours to write or revise a speech, and Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart are giving him a ride into town.

A liberal Democrat to the core, Schlesinger nevertheless loved American history. He came to fame in 1945 with his Age of Jackson, which is probably now being pulled from university library shelves for the next bonfire. In 1949 he wrote The Vital Center describing a political consensus that, arguably, he went some ways to subsequently undo. This consensus, which Schlesinger endorsed, was against Communism. Noting the “revival of American radicalism”, he writes: “Class conflict is essential if freedom is to be preserved because it is the only barrier against class domination; yet class conflict, pursued to excel, may well destroy the underlying fabric of common principle which sustains free society.”

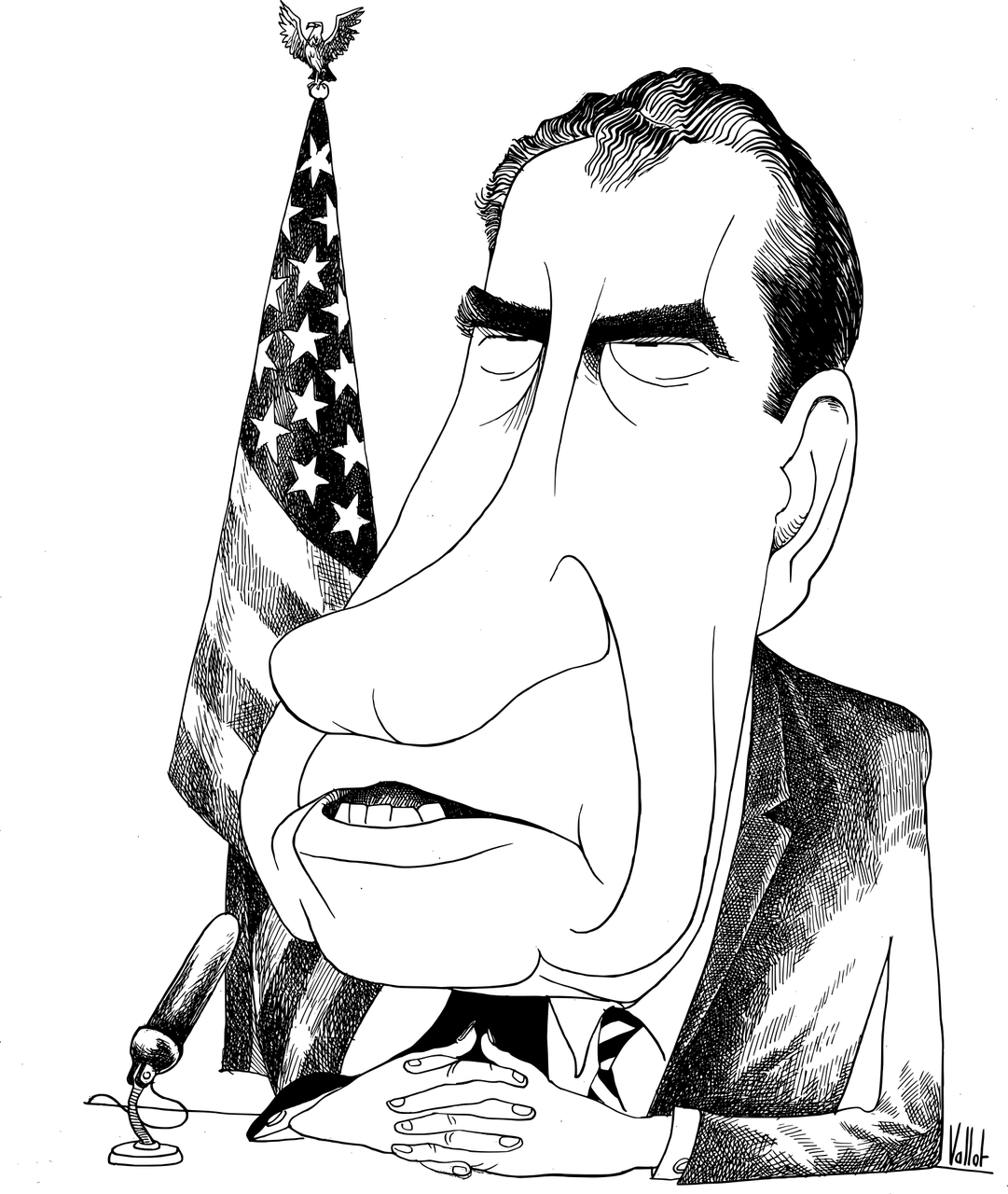

Vital Center was published between the two Hiss trials. Chambers lauds the role of Richard Nixon, then a first-term Congressman, who never doubted Chambers when the case seemed lost. There was probably not a politician who Schlesinger loathed more than Nixon. In 1981 Nixon moved into the house facing Schlesinger’s on Manhattan’s upper east side. The two gardens abutted each other. Schlesinger describes seeing Nixon in a three-piece suit and tie “rather stiffly throwing a large rubber ball to a grandchild.” That afternoon his wife gave a book party for a memoir by Sally Belfrage, daughter of a black-listed Hollywood author (incidentally, that book provided the inspiration for Sylvia Stone in my Red Line Blues). Invited to the party was Alger Hiss. “I had not supposed he would come,” Schlesinger wrote, “because I have long since publicly declared my belief in his guilt.” He came. They talked. “How odd,” Schlesinger wrote. “To begin the day with Nixon and to end it with Hiss!”

There is a comfort to the familiarity of our fiery moment because we know that it will pass. And for all those who confront the ever-present crisis with a temporary rage, the majority console themselves with a Chambers-like faith. And one day we will see our enemies over the wall playing catch with their grand-children and chat idly at a book party with those who we believe were traitors. Sic transit Gloria mundi.

*****

Photo by OpenClipart-Vectors (Pixabay)

Comments