We live in a time when virtue is not considered very interesting. Once upon a time in America, though, virtue was viewed very differently.

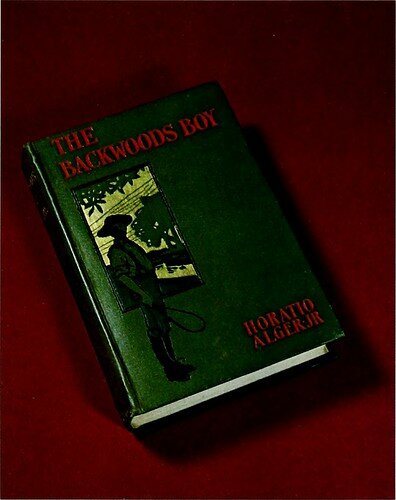

In the mid- to late(ish)-19th century, wrote a series of novels centered around young men who were the embodiment of American virtue. They weren’t gentlemen by lineage, they were gentleman by character. In his series of bestsellers, Alger churned out seemingly endless stories about teenagers, or even boys of 10 or 11, who were hard-working, honest, kind, courageous, and invariably willing to take a stand when it come to doing the right thing, no matter the temptations to do the wrong thing.

For the boys and young men across America who couldn’t get enough of Alger’s books, it didn’t matter at all that the plots were cut from the same template or that the heroes were interchangeable. What mattered was that Alger promised a payout on the American dream: If you work hard, are honest, cultivate virtue, and seize opportunity when it offers itself, then you too can make the journey from shoeshine or newspaper boy to a well-paid office clerk with a straight shot to being president of the company one day.

At much the same time that Horatio Alger was a bestseller for boys, Louisa May Alcott was also writing books that focused on virtue, although hers were meant for girls. Because Alcott was the better writer than Alger, whose books faded away as America moved into the 20th century, Alcott’s books have stood the test of time and are still — although just barely — part of the American canon. Even across a span of 150 years or more, her characters reach out to us. They are real people.

Unlike Alger’s one-dimensional boys, Alcott’s girls are multi-faceted. They reminded readers of themselves or of their friends or siblings. What was especially appealing was that Alcott’s girls weren’t always good, something that made it easier for the young women who read the books to relate to them. For example, her most famous character, Josephine “Jo” March, from Little Women, was constantly getting into scrapes, whether because she was well-intentioned but careless or because she allowed herself to give in to her worst impulses. Always, though, Jo felt true remorse for her conduct; occasionally she suffered greatly as a result of her poor choices; and she consistently learned and grew as a person.

Alcott was careful to ensure that, by book’s end, Jo hadn’t turned into a boring, plaster saint. Instead, she made it clear to her readers that Jo, by virtue of having the right values and constantly striving towards goodness and truth, had made the journey from self-centered madcap to a fully realized adult, deserving of love and a quality life. This held true in other favorite Alcott novels, whether Old-Fashioned Girl, Jack and Jill, or the Aunt Hill.

Virtue continued to sell well into the early 20th century. Whether Lucy Maud Montgomery’s endlessly delightful Anne of Green Gables books, Gene Stratton-Porter’s Limberlost books, or Jean Webster’s Daddy Long Legs and its sequel (both of which delicately advanced Fabian socialism and eugenics), the authors’ compact with the reader was always that, no matter how foolish or error-prone the hero or heroine was, by book’s end, the characters would have gotten it right. They would have achieved a mature virtue that signaled to the readers what society’s expectations were about how good adults should think and act.

Nowadays, though, virtue is not a “thing.” At the low end, it’s considered boring; at the higher, intellectual end, it’s considered an unconscionable imposition of Western, white, male culture. Whether on TV or the movies, or in books, snarkiness, victimhood, self-righteousness, and aggression are the name of the game.

When my children went through English classes in high school, they never read a single book that advanced pure virtue as something to which all people should aspire. And yes, by virtue, I guess I do mean a classic Judeo-Christian notion of behavior, one premised on the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, and Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. Instead, my children read about feral school boys, South African prostitutes, gay loners, suicidal narcissists, and a host of other characters who were too deeply enmeshed in misery to bother with being good. Survival was the name of the game, whether in response to external adverse circumstances or internal miseries and conflicts.

I occasionally tried to get my children to read the classics, but without success. They told me that these books were “hard” to read and, worse, that they were boring. My kid and their friends wanted to read about pint-sized Walter Whites and Tony Sopranos, rather than to read about young people trying to find a moral pathway that would bring them existential satisfaction.

Thankfully, despite their reading material, my children are neither mobsters nor drug kingpins. Indeed, they’re fairly nice people, so the lack of moral decency in their reading material doesn’t seem to have caused any permanent harm. Nevertheless, I feel that our culture failed them by depriving them of moral role models.

Which gets to my own struggles writing a novel. I do believe that my main characters should stand for something good, especially because significant parts of the book will take place during the 1930s and 1940s, when evil was ascendant. My problem is making the characters seem like real people, like Louisa May Alcott’s girls, rather than boring plaster saints, in the mode of Horatio Alger’s boys.

As best as I can tell, the trick seems to be to give characters small vices and big virtues. They may believe in the Ten Commandments, but they’re allowed to be sarcastic (although they’ll apologize if they’ve hurt someone with their sharp tongue), thoughtless (although having hurt someone they vow to do better), and be really bad at certain life skills, whether cooking, painting, carpentry, or singing.

In other words, readers will tolerate someone “good,” provided that the same person isn’t so perfect as to be off-putting. It’s a delicate balance and one that has me constantly re-writing dialogue and whole scenes. Still, it’s a good discipline and one that, I hope, sees me creating a novel with characters whom people wish they could meet in real life.

******

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images

Photo by shawncampbell

Comments