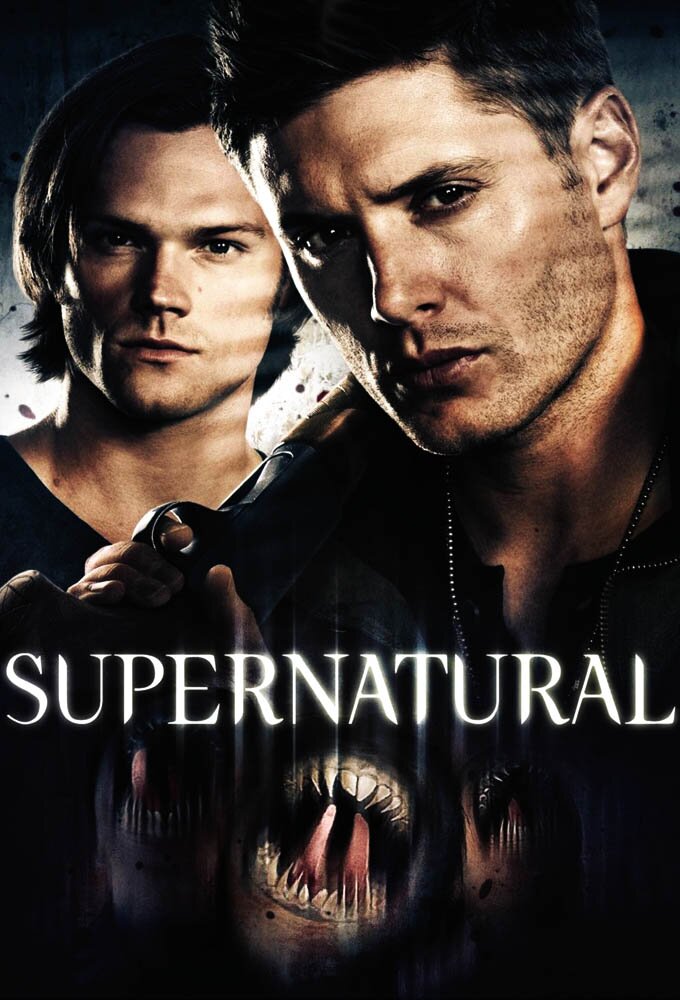

One of my cheap thrills is watching the CW show Supernatural. The interaction between brothers Sam and Dean Winchester and their friends, whether angel, demon, witch, or even human, along with imaginative and sometimes incredibly funny plots, has made it an engaging viewing experience.

In addition to the standard horror show and comedy shticks, the long-running show occasionally grapples with moral issues, in no small part because most episodes have the brothers and their friends killing “ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night.” Usually the monsters are presented as appropriately evil, but there have been times when these evil monsters have been trying to reform — and the brothers sometimes offed them anyway. Fun stuff, as I said…

An episode from two weeks ago set me wondering how the show will grapple with what I consider to be an overarching moral issue: How will the brothers teach their protégé, Jack, a powerful Nephilim, to be “good”? After all, as the show doesn’t shy away from acknowledging (although not explicitly so), with great power comes great responsibility.

The show’s first little stab at dealing with teaching Jack how to be good was to have another character, Donatello, a man without a soul, explain how he tries to be good: He asks himself what would Mr. Rogers do? Jack, unfamiliar with Mr. Rogers, reshapes the question to ask himself “What would Sam and Dean do?” because he considers them the best people he knows.

When the episode ended, I had a question of my own for a friend who also likes the show: How will Hollywood writers, of all people, handle teaching moral issues? After all, despite Harvey Weinstein’s long-ago boast that Hollywood’s “moral compass” meant it was exceptionally well-situated to teach the rest of the world about morality, most Americans, if they didn’t already question that idea when Weinstein said it, are certainly questioning it now.

Aside from the fact that Hollywood has few people equipped to teach morality, I believe that the Supernatural episode I watched started off on the wrong foot. That’s because the first rule it advances is simply to “copy someone.” That teaches mimicry, not morals.

(Incidentally, the principle that has people asking “What would Jesus do?” is about morals, not mimicry, because it requires people to look at his teachings as well as his acts, and Jesus’s teachings, especially to the extent they work through parables, are all about larger moral principles. The same cannot be said for either Mr. Rogers or Sam and Dean Winchester.)

In my experience as a parent, there are two ways to teach children behavior: One is through rules and the other is through principles. When they’re very little, because toddlers aren’t known for their abstract thinking skills or sophisticated vocabulary, rules are the way to go: “Do not pull the dog’s tail!” Rules, as you know, are very fact specific.

However, as children grow more sophisticated — and this can be as early as five or six — you can teach them larger principles: “Do not touch the dog in a way that you would not like to be touched. You don’t like it when someone pulls your hair and dogs don’t like it either.” That is the child’s first exposure to a moral principle: The hair pulling is an example; the golden rule is the principle.

Ultimately, rules are problematic because they don’t apply to all situations and because there can be loopholes. One of my friends, a child behaviorist, likes to point out the epic fail that results when parents announce this common rule: “Don’t let me see you hit your sister.” Every kid eventually finds the loophole: The rule as stated isn’t about hitting, it’s about being seen hitting. If Mom doesn’t see you hit your sister, you’re gold.

I like to analogize the difference between rules and principles to the difference between the cardinal points on a compass and the list of instructions your friend gives you to find her house. The cardinal points on a compass are fixed. No matter the direction in which you’re facing, north is always north. The same holds true for the other directions. North, south, east, and west apply to all situations in which you may find yourself. If you have a map and know your cardinal directions, you will always find your way.

Meanwhile, that laundry list of left and right turns your friend sent you is a delusion and a snare. It seems so easy in the beginning. You turn left here and right there, all while keeping an eye out for the church with the tall white steeple — and as long as it’s daylight, you’re safe. But what happens when darkness falls and you realize that you missed a turn? Without a map, without cardinal directions, you are utterly and completely lost. You don’t know where you’ve been and you don’t know where you’re heading. You had a list of rules, but the situation to which they applied has changed.

The biggest rules of all, of course, are the Ten Commandments. As Dennis Prager points out in his wonderful video series about the Ten Commandments, these rules apply to all situations in which humans can find themselves. Sure, there will always be nuances and exceptions, but the Commandments’ reach provides guidance even in those situations. You just have to work a little harder.

One example of working a little harder is the Eighth Commandment — “Thou shalt not steal” (Exodus 20:15). Superficially, it seems to apply only to snatching apples or gold coins. Properly understood, though, it reaches slavery, which is stealing a person’s liberty and murder, which is stealing a person’s life.

In the same wise vein of overarching principles, think about the Sixth Commandment, which is commonly translated as “Thou shalt not kill.” (Exodus 20:13.) That simple statement has caused a great deal of anguish for conscientious objectors over the years. It would undoubtedly help them to know that “kill” is a mis-translation of the original Hebrew. What the Commandment actually says is “that shalt not murder,” with murder being understood to mean the wanton and inexcusable taking of a human life, whether in cold blood or the heat of passion. Just as our laws do, the Bible recognizes that human experience will give rise to situations in which killing is defensible, such as self-defense, complete accident or the defense of another, not to mention fighting in a just war.

As I work on my novel about my family’s experiences in Western Europe and Israel during the 20th century, I’m constantly trying to figure out how to imbue my work with moral principles that aren’t tedious little rules that are applicable only to one situation or another. My parents and their parents had to address these principles in three wars (including one complete with genocide) and a Depression. Given that enormous canvas, I don’t want to cheapen my novel by writing little anodyne statements about what’s good and what’s bad in any given situation.

My hope is that the writers behind Supernatural start doing the same. This season and the next will be boring if the episodes just say “Jack, you can kill this ghosty, but not that ghouly,” without giving him any bigger insight into the value of human life or the difference between murder and other killings.

What I would say to any writer is that exploring principles is intellectually invigorating and leads to subtlety and nuance. Listing off rules is tedious and numbing, and brings no larger insights to the characters or the audience. Moreover, I think Americans are hungry for principled sustenance, provided it’s presented in a way that grabs them both emotionally and intellectually. In other words, Americans aren’t as dumb as Hollywood thinks they are.

Comments