In an interview with Comic Book Confidential in 1988, Frank Miller remarked that 1980s America was a “very frightening, silly place… it’s often silly and frightening at the same time and [he] hope[d] [The Dark Knight Returns] is silly and frightening at the same time.”

Editor’s Note: Click here for Part 1 of this ongoing series. Warning: spoilers in this and the previous installment.

You do not have to read very far in The Dark Knight Returns to realize that Miller can indeed illicit horror and laughs on the same page, if not in the same panel. Miller’s genius at combining these two seemingly contradictory responses lead to some intriguing commentary on criminality and society’s response to it. And like Miller’s satirical attacks on the media, his observations on modern America’s inability to seriously deal with crime make interesting parallels with the Trump era.

To begin, it is important to notice how ridiculously exaggerated crime is in Miller’s Gotham. On the second page of the book, a newscaster reports on the slaying of three nuns by the Mutants, a large gang of teenagers that terrorizes Gotham city during the book’s first half. This gang repeatedly threatens to murder Police Commissioner Jim Gordon, kidnaps a ten-month old baby as ransom for the family’s fortune, and comes close to a complete takeover of the city before Batman finally puts a stop to them.

But it is not only new villains that make an appearance here. Classic Batman villains Two-Face and the Joker are also present, and Miller takes their evil to new heights. The Joker, for example, murders everyone during a live recording of a late night talk show and then proceeds to go on a killing spree at a carnival, murdering even children without the slightest bit of remorse.

While such shocking acts of evil are scary enough, the true crime is society’s response to the criminals. Throughout the course of the book, the media and the government are completely incompetent at even recognizing evil for what it is. Instead, these criminals are “marginalized,” “troubled,” or “misunderstood.” Rather than locked away, Gotham’s villains are almost treated like celebrities. The Joker is allowed as a guest on “The David Endocrine Show” (an obvious parody of David Letterman), and everyone laughs at him as if he’s just another socialite or stand up comic. One of the most subtle jokes on this trend is what Miller does to Arkham Asylum. In traditional Batman comics, the institution is known as a place for the “criminally insane.” In The Dark Knight Returns, however, Miller makes Arkham Asylum the “Arkham Home for the emotionally troubled.”

In fact, throughout the entire 199 pages of The Dark Knight Returns, neither the media or the government rarely use the term “evil.” The closest person that reaches that description in their mind is Batman, and even then, they can never go as far as to invoke moral categories. One of the best examples of this is when Dr. Bartholomew Wolper, the socially progressive psychiatrist and Batman’s biggest critic, calls Batman a “menace to society”, and then immediately apologizes for having to use such an “outdated term” (113).

Batman is not the only one that the media criticizes for being tough on crime. On the opening pages of chapter two, Commissioner Gordon is confronted at gunpoint by a teenage member of the Mutant gang. Gordon kills the gang member in self-defense, but the media really puts the emphasis on the fact that Gordon shot the teenager. “Commissioner,” a reporter asks, “You just shot a boy, how does that feel?” As if Gordon spends his days shooting teenagers as a fun pastime (61).

The government is no less ineffectual at dealing with crime. Gotham’s mayor, portrayed as a dithering politician who can never make up his mind about anything, attempts to negotiate with the Mutant gang leader instead of sending law enforcement after the gang. The leader promptly tears him to shreds.

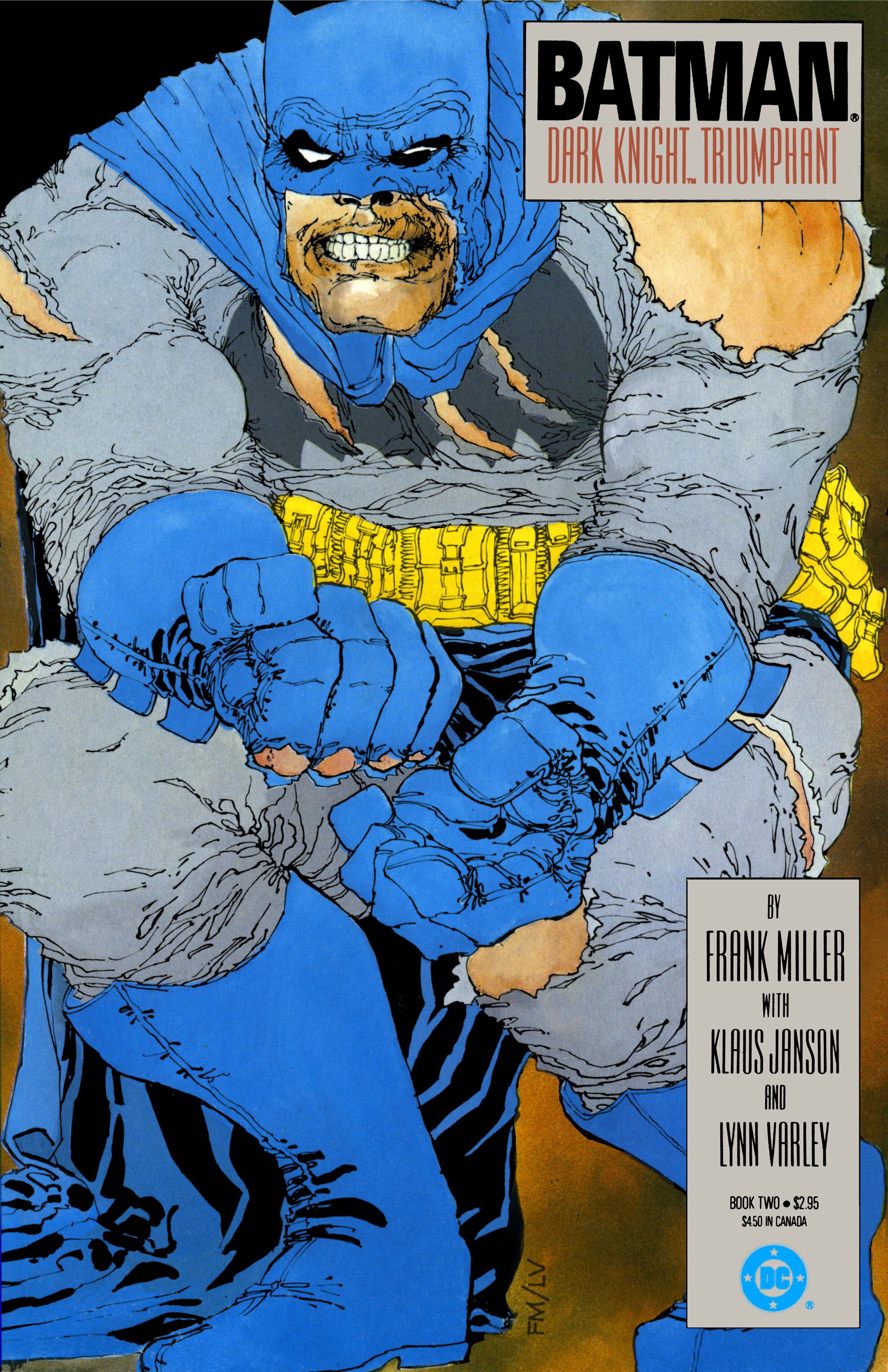

This all brings us to the problem of Batman. Frank Miller’s portrayal of the Caped Crusader has often been criticized for being crazy, authoritarian, and obsessive. While the Batman of The Dark Knight Returns is not nearly as extreme as in Miller’s later Batman works, it still pushes Batman in a far darker direction than we are used to seeing. Even though Batman still never goes as far as to kill anyone, he uses rubber bullets, threatens to kill criminals, and has a Batmobile that looks like a tank. In a memorable scene, Batman is pursuing one of Two-Face’s henchmen. The goon, cowering on the floor, cries out “Stay back — I got rights,” to which Batman responds with “You’ve got rights. Lots of rights. Sometimes I count them just to make myself feel crazy” (44-45).

Clearly Batman is not a pioneering advocate of criminal justice reform here…

By painting Gotham’s criminals as so depraved however, and by also portraying Gotham authorities as so incompetent, Miller sets the stage for a more sympathetic Batman. Sure, vigilantism and just roaming around the city beating up criminals may sound unconstitutional and proto-fascist, but given the circumstances, can you really blame Batman?

Perhaps the clearest example of this is when Batman rescues a baby that has been taken hostage by the Mutant gang for ransom. In a tense sequence of panels, one of the gang members, desperate now that Batman has incapacitated the other members, puts a gun to the child’s head and starts screaming “Back off, man–I’ll kill the kid–Believe me, man, I will–Believe me” (64). Batman promptly shoots the gang member (without killing her) and rescues the child, darkly saying “I believe you” (65). This is obviously a very dark scene, and pushes Batman farther than he would normally go, but as we recoil in shock at how much Batman is willing to take the law into his own hands, we also understand that he is the only one in the city that takes crime seriously.

While Batman believes the threats of Gotham’s criminals, the city’s media and politicians would rather smile condescendingly and treat such threats as the symptom of social marginalization. While Batman’s vigilantism may be dangerous, in Miller’s view, the apathy and naivete of everyone else’s approach to crime is even worse, because it leaves the most innocent Gothamites (such as nuns and children) open to the most brutal acts of violence.

So how does all this tie back to Trump? Remember that Trump openly called himself the “law and order” candidate, claiming that the other politicians in Washington did not take crime seriously enough. In some ways, he certainly is right. From the Democrats’ allergy to talking about the dangers of illegal immigration and crime, to Democratic nominee Lincoln Chafee’s ridiculous proposition to negotiate with ISIS, there is obviously a tendency on the Left to be soft on crime. At the same time, Trump often responded to these excesses with ridiculous and morally bankrupt excesses of his own (such as killing the family members of ISIS terrorists or banning all Muslim immigration).

“But not so fast,” the Trump supporter would say. “Sure Trump has said some crazy things, but what is more crazy is the refusal of political elites to acknowledge the criminality of those illegally crossing our border, or of those that would murder innocent Americans in the name of Islam. Trump maybe ‘crazy’, but maybe ‘crazy’ is what we need right now.”

This is essentially the line that Batman supporters take throughout The Dark Knight Returns. When a news anchor asks Batman supporter Lana Lang about the constitutional violations inherent in Batman’s war on crime, Lang completely evades the question by saying that “We live in the shadow of crime… with the unspoken understanding that we are victims — of fear, of violence, of social impotence. A man has risen to show us that the power is, and always has been in our hands, we are under siege–he’s showing us that we can resist” (66). Sometimes “roughing things up” (to borrow a phrase from Trump) is necessary to keep things in order.

Miller takes this idea to an extreme in the last chapter of The Dark Knight Returns. After the country falls victim to a nuclear winter (yeah, the plot to this book escalates rather quickly), the United States descends into chaos. Gotham is no exception to this, and crime and disorder flourishes. Even the civilians of Gotham quickly regress to a Hobbesian “state of nature” as they fight each other for food and natural resources. This all changes as Batman rides into the city on horseback with an army of disaffected Mutant gang members, now rallied to Batman’s cause. Batman effectively takes control of the city, as he and the pro-Batman mutant faction (now called the Sons of the Batman) institute a strict reign of law and order and Gotham. “Tonight, we are the law,” Batman proclaims to his Mutant allies before riding into the city. “Tonight, I am the law” (Miller, 173).

At face value, this statement confirms the suspicions of Batman’s staunchest opponents. Here is Gotham’s “protector,” exploiting a city-wide crisis to fulfill his own fascistic desires. But as the nights wear on and Batman gradually takes more control of the city, it is hard for us not to be thankful that Batman decided to act when he did.

Through undeniably ruthless methods (including physically attacking uncooperative civilians), Batman is able to pull the city together and get the people of Gotham to cooperate to put out fires and share food and supplies. A week after the initial blackout, the rest of the country is still in ruins, while thanks to Batman, Gotham city is able to pull through the disaster. Here is where Miller raises a somewhat distressing question. Batman’s methods are unquestionably authoritarian, but it is those methods, not democratic norms or the constitutional rule of law, that saves Gotham City. Democracy? The constitution? The rest of the country (theoretically) has those things in spades, and they don’t seem to fare well, do they? The same way Lincoln circumvented habeas corpus during the Civil War, Batman ignores any questions about the rule of law or the legitimate use of force in order to save Gotham from itself. Miller puts forward a dangerous (even if correct) argument that in times of crisis, authoritarianism must win out over democracy.

Believe it or not, this is a similar argument put forward by Trump supporters to justify apologizing for or ignoring his every silly remark or immoral action. Dennis Prager, a very influential voice in the conservative movement and one of Trump’s strongest supporters, argues that conservatives should not spend too much time attacking Trump because America is currently in the midst of a cultural Civil War.

The Left is engaged in a bitter fight for control of this country, and will resort to almost anything (even, Prager emphasizes, physical violence) to achieve their ends. Now is not the time for fussing about a few crude remarks or silly tweets. Yes, Trump says some regrettable things, but he is ultimately a symptom of this country’s problems, not a disease. Just as Batman is a necessary reaction to Gotham’s relentless crime waves, Donald Trump is a necessary reaction to the excesses of the cultural and political Left. While the rest of America’s politicians refuse to face the nation’s problems, Trump is the only one who is willing to call out the evils of radical Islam or the dangers of unchecked immigration.

Some of you may be thinking that this is a rather frightening and silly argument. But after all, as Frank Miller said, America can often be a frightening and silly place.

Comments