“Mr. Chief Justice—and may it please the Court—the ‘Cold War’ is not just a phrase, Your Honor. It’s not just a figure of speech. Truly, a battle is being fought between two competing views of the world. I contend that Rudolph Ivanovich Abel—Colonel Abel, as he was called even by the men who arrested him—is our foe in that battle.

“He was treated as a combatant in that war, until it no longer suited our government to so treat him. Accordingly, he was not given the protections we give our own citizens. He was subjected to treatment that, however appropriate for a suspected enemy, was not appropriate to a suspected criminal.

“I know this man. If the charge is true, he serves a foreign power, but he serves it faithfully. If he is a soldier in the opposing army, he is a good soldier. He has not fled the field of battle to save himself—he has refused to serve his captor—he has refused to betray his cause. He has refused to take the coward’s way out. The coward must abandon his dignity before he abandons the field of battle—that, Rudolf Abel will never do. Shouldn’t we, by giving him the full benefit of the rights that define our system of government, show this man who we are? Who we are? Is that not the greatest weapon we have in this Cold War? Or will we stand by our cause less resolutely than he stands by his?”

One of the great fallacies of the “BOYCOTT HOLLYWIERD!!!” movement is to assume that the politics of the filmmakers and/or cast of a movie/show is far more important than the actual politics of the end product. Tempting as this shortcut may be, it’s the exact opposite of the truth. The truth is: “Life is short, but art is long.” An artist’s politics only effects the moment. The art itself lasts forever.

Victor Hugo sympathized with socialists, but his works are monuments to the individual (as Ayn Rand noted in her forward to an edition of Ninety-Three). George Orwell considered himself a “Democratic Socialist”…and yet he wrote Animal Farm and 1984.

Today, we have Joss Whedon.

We also have Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Both well-known Democrats—and Spielberg in particular is known to frequent Democrat fundraisers. However, two things worth noting:

First, at least as far as I’m aware of, neither Spielberg nor Hanks have ever gotten particularly vocal about politics (aside from Hanks voicing an Obama documentary, or something)—they understand, as Michael Jordan did, their respective trans-political appeal, and the value thereof. They know better than to spoil that. In the meantime, how they spend their money is their business.

Second, Spielberg and Hanks have often given us wonderfully Conservative-friendly stuff over the years—and sometimes, it even crosses the line into truly Conservative.

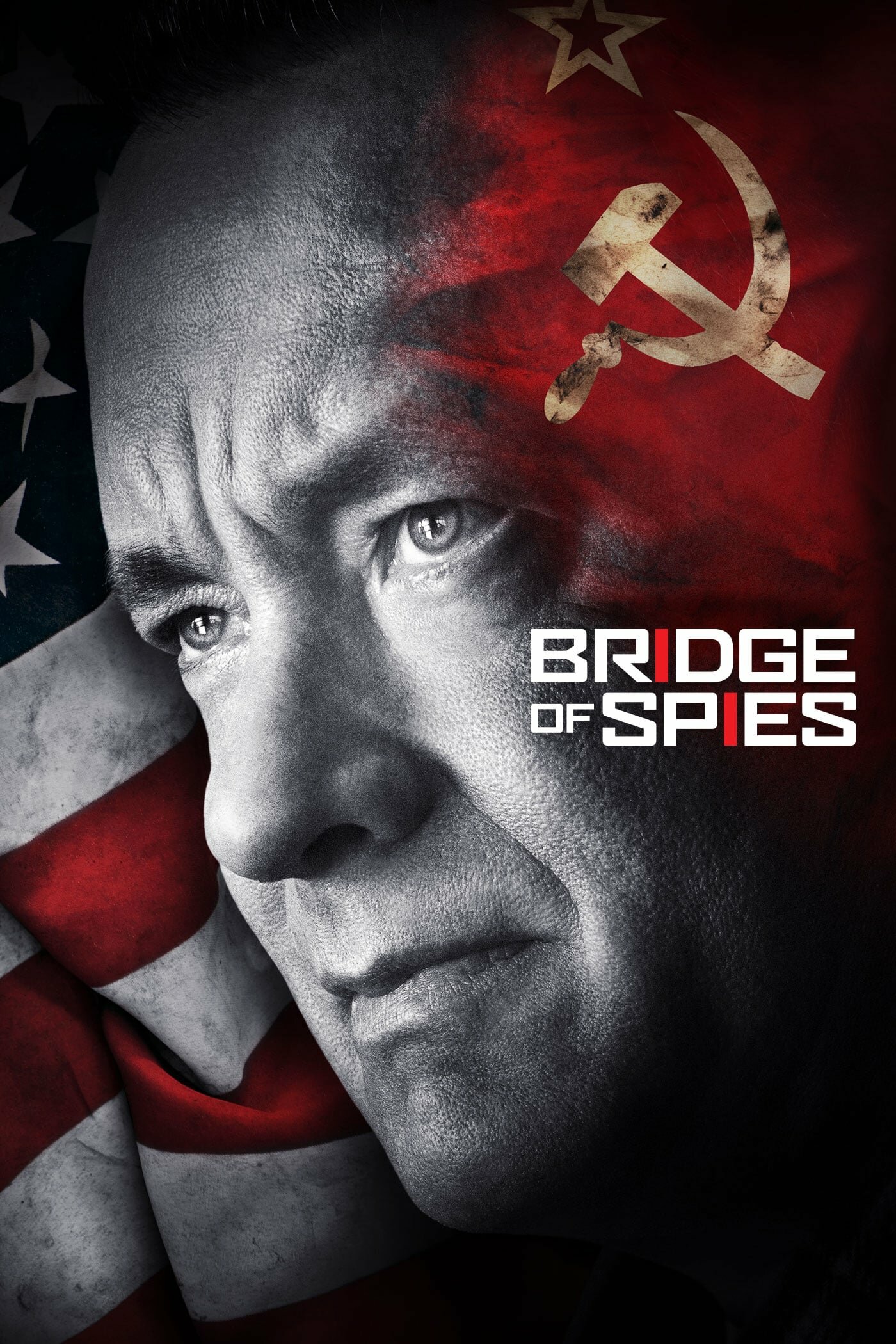

This is one of those times. Bridge of Spies is a masterful Cold War thriller about a little-known event in our history…and to Spielberg’s considerable credit, it centers thematically on the Cold War itself—why it existed, and who the villains truly were.

If you ever needed proof that Hollywood is not a monolithic entity, even in our current hyper-partisan times…look no further than this Oscar-winning film, a modern masterpiece from one of our greatest filmmakers (well, three, actually), and one of our greatest stars.

Editor’s Note: In April of 2017 writer Eric M. Blake began a series at Western Free Press naming the “Greatest Conservative Films.” The introduction explaining the rules and indexing all films included in the series can be found here. Liberty Island will feature cross-posts of select essays from the series with the aim of encouraging discussion at this cross-roads of cinematic art with political ideology. (Click here to see the original essay. Check out the previously cross-posted entries on Jackie Brown, Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Unforgiven, Hail, Caesar!, Apocalypse Now, Fight Club, Man of Steel, Batman v. Superman: Dawn Of Justice ULTIMATE EDITION, Wonder Woman, Kill Bill, Gran Torino, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, Blazing Saddles, The Magnificent Seven, Shaft, Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, and The Enforcer.) If you would like join this dialogue please contact us at submissions [@] libertyislandmag.com.

WHY IT’S A CONSERVATIVE FILM:

The Left nowadays has a bitterly hilarious “memory” of the Cold War era. As a rule, the whole “Communist threat” issue is mocked and derided—you know, “McCarthy-era paranoia”. To hear the average Leftist talk about it, you’d think there was no “Communist threat”, and we really had nothing to worry about.

Soviet agents? That’s just paranoia—that’s The Red Scare! Americans were turning against each other over a threat of “Communist Spies” that didn’t really exist…right? And besides, the Soviet Union was going to fall anyway!

Never mind these same Lefties swore up and down during the Cold War that the Soviets were invincible and the idea of surpassing them was naïve at best, dangerous at worst. I’m pretty sure about the only guy who actually said at the time that a Soviet downfall was inevitable was…Ronald Reagan.

But I digress.

Again, that’s the two things Lefties will say about the Cold War, now that it’s long over: 1) The USSR was going to fall eventually, anyway, and thus the Soviets posed no real threat unless we would’ve provoked them; and 2) Any talk at the time of “Soviet spies” was paranoid nonsense…because the Soviets didn’t do that kind of thing, except in our pathetically vivid McCarthy-esque imaginations. And maybe in the movies.

Well, give Steven Spielberg his due. Movie or not, he clearly knows better than to fall prey to that self-righteous pretentiousness. The opening text:

1957.

The height of the Cold War.

The United States and the Soviet Union fear each other’s nuclear capabilities—and intentions.

Both sides deploy spies—and hunt for them.

Inspired by true events.

The whole scenario was for real. The Soviets did in fact send spies to infiltrate our society and apprehend our secrets. Suggesting otherwise is…naïve. And Spielberg knows it.

TRIAL ONE—BECAUSE SOMEBODY HAS TO:

Jim Donovan, insurance lawyer—with a past as a prosecutor for the Nuremberg trials. An all-American guy, with a solid code of honor. Who better to represent America—in a battle of image, no less?

And so, just after the FBI captures KGB Col. Rudolf Abel, his firm’s approached by the feds to represent the agent’s defense…and the firm puts it on Donovan:

“It’s important to us—it’s important to our country, Jim—that this man is seen as getting a fair shake. American justice will be on trial. …Jim, look at the situation. The man is publically reviled.”

“And I will be, too!”

“Yes, in more ignorant quarters—but that’s exactly why this has to be done, and capably done. It can’t look like our justice system tosses people on the ash heap.”

Jim takes the case—knowing full well how it’ll tarnish his public image. But it has to be done, because, as he tells his wife, American justice must be based in “a court of law—not a kangaroo court!”

And as complicated as things become over the proceedings—particularly regarding public opinion—Donovan’s hopes are still vindicated. Col. Abel notes to Donovan that he was not mistreated by the CIA during the interrogation. And though the FBI conducted a warrantless search—and Donovan’s appeal to dismiss the evidence obtained is overruled—even Abel accepts it as par for the course, as he’s not an American citizen. At any rate, Donovan succeeds in convincing the judge to waive the death penalty. It’s good to have insurance, in case we need to negotiate with the Soviets for something….

Still, he pushes to have a second trial, in the Supreme Court, to make darned sure that due process is observed. Because he doesn’t believe in kangaroo courts.

A WORD ABOUT “WHO WE ARE”:

At first glance, Donovan’s speech to the Supreme Court—the page quote, above—might remind some of us of the Leftist self-righteousness about the War on Terror. “That’s not Who We Are!” and so forth.

And yet, there’s a major difference—a difference Obama, remember, failed to acknowledge when he compared meeting with the Soviets without preconditions to doing the same for, say, Iran.

Namely…the Soviets didn’t want to just destroy perceived enemies. It wasn’t about that—not per se. It was about expanding its influence. The Cold War was a battle of ideas—of intrigue—of espionage. It was a battle of which philosophy would come out on top.

Otherwise, the Cold War would’ve turned “hot” early on.

And that’s how Donovan frames the whole scenario.

Besides…say what you will about the Reds, but they cared about image—they cared about looking, at least, like they followed the rules of international relations. Because in a conflict like that, it matters very much who looks the most like “the good guy”, to the world.

And for all our flaws, America looks very much like “the good guy” in this movie. Like Jimmy Stewart before him, Tom Hanks embodies in the character of Jim Donovan everything that’s noble and pure about us.

TRIAL TWO—AMERICAN JUSTICE VS. SOVIET TYRANNY:

As the second trial progresses…an American Air Force pilot, Lt. Powers, is reassigned to the CIA. He is shot down, and captured by the Soviets. And it’s painfully clear the USSR has far different ideas than we do about “justice”—particularly towards spies.

In a powerfully vivid sequence, the two trials are contrasted. The Supreme Court is shown to be beautiful, and dignified—the music softly patriotic. The Soviet court, however, looks down on the pilot from on high as tyrants. The setting is dark and imposing, blood-red banners and blazing symbols amid grey walls—the music dark and dreary. All around the pilot are stiff, solemn and cold. When the sentence is levied…all stand as one, applauding as one. A collective. Cold. Cruel.

The difference is stark as night and day: Tyranny…and Liberty.

Later, Abel’s treatment by the CIA and Powers’s by the KGB is further contrasted. Powers is doused with a bucketful of water and subjected to psychological pressures that Abel clearly has no reason to brace himself for.

Tyranny vs. Liberty. Communism vs. Capitalism. USSR vs. USA.

“WHAT MAKES US BOTH AMERICANS?”

Early on, a CIA agent tries to get Donovan to bend his attorney-client confidentiality just this once—to see if Abel’s told him anything. As far as we know, Abel’s told him nothing…but that’s not the point. Donovan refuses to let on about anything—and his reason why is telling:

The value of the Constitution. It’s what makes us Americans, as opposed to anything else. Nothing else matters, on that.

As far as Donovan’s concerned…it’s not a “living, breathing document” to be bent because it’s convenient. It’s a rule book, to be followed and believed in. Because real Americans don’t believe in tyranny…like the Soviets clearly do.

And this integrity impresses Abel, who compares him to a “standing man” he remembers from his youth, whose quiet dignity and refusal to break stopped further beatings from Soviet officials.

THE BERLIN WALL:

Soon after the trials end, Donovan’s given a new assignment—a prisoner exchange, on the border to East Berlin. And he’s alerted to some new intelligence…that they’re preparing to seal off the East, to prevent emigrants to the West.

Thus enters the notorious symbol of Communist tyranny—the Berlin Wall. Cut to a harrowing, tragic sequence when a young student tries to rescue the woman he loves from East Berlin before the Wall is completed. Alas, it’s too late for him to escape—and the Stasi will not recognize his papers. He’s now a second prisoner in a now more complicated deal, as the East Germans want their piece of the pie.

This sequence powerfully underlines the evils of this tyranny. The film refuses to engage in any moral equivalency—the Communist system is shown as evil, no ifs, ands, or buts. The humanity of Abel is individual—and we repeatedly get the idea that the USSR does not deserve his loyalty.

Further, note the line below, as an agent briefs Donovan in Berlin:

“Food is scarce over there and things have started to fall apart. There are gangs, and rule of law is less firmly established over there.”

West Berlin, of course, has no such issues. Donovan even orders a big American breakfast at the Hilton.

The contrast between East and West Berlin, emphasized for all to see and hear. It’s painfully obvious, then, which system works.

THE ART OF THE DEAL:

In the end, the trade of Col. Abel for Lt. Powers and the student all comes down to the negotiation skills of Jim Donovan. The fate of three lives—and perhaps so much more—is in the hands of a private citizen.

And we see him play his part beautifully, seeing through and cutting through the games and doublespeak to gain the upper hand in this three-way chess match with the Russians and the East Germans.

Meanwhile, it’s his idealism and heart that motivates him to try for both Powers and the student, though his CIA contacts tell him to just go for Powers. And thankfully, his ideals—his virtues, as a “mere” American citizen—win the day.

To boot, the ending text notes that Donovan went on to negotiate the release of prisoners in Cuba for JFK…and ended up saving a lot more people than planned, including women and children.

Not bad for an insurance lawyer, huh?

FOR BONUS POINTS:

Early on, Donovan makes it a point to bring up the Rosenbergs, to contrast against Abel:

“The Rosenbergs were traitors. …They gave atomic secrets to the Russians. They were Americans, they betrayed their country.”

Significant? Darn right it is. Part of the Left’s revisionist history has been that the Rosenbergs were innocent—falsely accused of treason and espionage as part of The Red Scare.

Well, Spielberg and Co. make it a point to defy that revisionism. Kudos to them, once again.

When the deal with the Russians is made, Donovan makes it a point to ask if Abel will be in any real danger once returned to the Soviets. The Russian representative shrugs and says, “Well…goodness: As things are now, everyone is in danger.”

Which society is “paranoid”, again?

Just to be clear: Throughout the first half of the film, we do see examples of the fear filling America in the late 1950s—from the notoriously useless bomb drills to people lashing out at Donovan and his family. However, as the film goes on, the situation in the Soviet sphere of influence is shown to be much, much worse.

Especially when Donovan finds himself witnessing the Stasi gunning down someone who dared try to climb the Berlin Wall.

WHY IT’S A GREAT FILM:

Steven Spielberg is the undisputed Reigning King of Hollywood. Round about everyone living any length of time in the Western world can instantly recognize the titles of his classics—Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., the Indiana Jones trilogy, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan…

He’s one of the greatest movers and shakers in the industry. His name is synonymous with Grand Cinema—with films powered by a childlike wonder and eagerness for adventure. Spielberg knows that golden formula of maximizing both Entertainment and Art. He is a master. He is a legend.

Does he have slip-ups? Well…no more than any other master filmmaker with such a long career. War Horse, depending on who you ask, may be excessively sentimental. Regardless, it frankly gets much harder to instantly, spur-of-the-moment name a title of one of his films off the top of your head when you pass Private Ryan on the timeline. Maybe Minority Report. Maybe.

Still, more than anything else, it makes most of his latter-day films underrated gems. Bridge of Spies hasn’t really been talked about since Mark Rylance won his Oscar. Still…it’s one of those gems. I certainly haven’t forgotten it.

The screenplay was written by none other than Joel and Ethan Cohen. That’s right—the Cohen Brothers, of No Country For Old Men and The Big Lebowski. But there’s none of their trademark wackiness and play against cinema conventions. This is a straightforward, albeit complex, drama-thriller.

TOM HANKS AS JAMES B. DONOVAN:

The quintessential all-American guy. Lovable and endlessly charismatic. That easy charm and playful nature. Confident yet vulnerable. And more talented than most can hope to be. Such is Tom Hanks.

Through him, we see Donovan’s idealism, underneath a dark wit. He’s pragmatic enough to assess the situations he finds himself in—clever, and pointed. Yet, we always see right to his heart, his eyes betraying his kindness, decency, and warmth.

Tom Hanks could give us nothing less.

MARK RYLANCE AS COL. RUDOLF ABEL:

Rylance won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for this role—beating Sylvester Stallone for the latter’s performance as Rocky Balboa in Creed. While I would’ve personally preferred Sly win for his powerfully poignant return to his classic role…still, Rylance was nonetheless a worthy victor.

Serenely accepting of whatever fate befalls him, Col. Abel is a man used to the strict discipline of tyranny. We constantly feel for him—even as we’re shown, all the while, that his loyalty to his government is misguided, and has gotten him nothing but hardship. He’s a good man, at heart—full of noble qualities. But we still know that he’s wrong in where his loyalties lie.

It’s complex. We still like him. He and Donovan form a nice chemistry, helped by Abel’s dark sense of humor.

“You’re not worried?”

“Would it help?”

We feel for him…to the very end. A tragic figure, who’s wrong on so much…and yet noble in all of it. Maybe even heroic…in his own way.

Of course, as far as Abel’s concerned, it’s Donovan who’s the real hero. And in that, at least, he isn’t wrong at all.

A MOMENT OF NOIR:

The rain hits hard in the dead of night. Street lights create islands of darkness amidst the shadows. Jim Donovan stands near such a light, complaining about a taxi passing him by with a light on. Then he walks down the sidewalk…as a mysterious man in trench coat and fedora follows him.

Beautifully shot—mist coming up from the rain hitting the asphalt and whatever cars are parked in the area…and while it’s shot in color, it has all the feeling the classic black-and-white gave us in the classic era. The shadow and the hard light—the suspenseful score, with a clarinet. And after the pursuer reveals himself to Donovan, we next see them seated in a lounge, a smooth jazz record plays in the background, as they have a talk.

The essence of Film Noir, beautifully recreated by Spielberg. Masterfully done, sir.

THOMAS NEWMAN’S SCORE:

Alas, Spielberg regular John Williams didn’t score this one. This time, the director brought on Thomas Newman—a great composer in his own right. His score isn’t as “big” or sweeping as something we’d expect from Williams. It’s more…contained—and yet, highly emotional, when it needs to be. It’s the score this film needs—for it isn’t a “high adventure”. It’s a deep, intricate drama—filled at once with intrigue and with human emotion.

THE BRIDGE:

The climax—the final arrangement, the exchange. It’s a solid tour-de-force in tension…and closure. And it reminds us of Spielberg’s mastery of cinema—in directing actors and directing the camera. Every shot is perfect. I have two favorites in particular.

The first is when Donovan and Abel discuss how Jim can tell if the Soviets have accepted the colonel back, or if they’ll treat him as a traitor. The camera starts on their backs…then pans to their faces, starting on Abel, then moving to Donovan.

The second…once the exchange is all over. Donovan is the last to go…watching Abel shown into the car. It drives off…and the last shot of the sequence: a wide shot of the now-darkened bridge, only a lone figure standing there…silent, unmoving.

“Uh, I, uh…I sent you a gift, Jim. It’s a…it’s a painting. I hope it has some meaning to you.”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t think to get you a gift.”

“This is your gift. This is your gift….”

BY THE WAY…

The Cohen Brothers have at times touched on politics in their film career—and those touches come across as pretty Conservative. Stay tuned for a possible future entry in this series….

Buy the movie here. And stay film-friendly, my friends.

Comments

Leave a Reply