“Don’t ‘Tom’ me, man.”

Before I focus on Shaft, I’d be remiss if I didn’t dwell on something I hinted at in my article on Jackie Brown: namely, exactly what happened to the classic Blaxploitation movement of the 1970s—why it died a sudden death.

Basically: The studios got scared out of making those kinds of films, because the post-MLK self-proclaimed Civil Rights leaders started branding it “racist”.

This was, of course, complete nonsense. Black audiences en masse went out in droves to watch these movies—and why not? Blaxploitation was, when you really got down to it, nothing more than classic genre pictures—detective thrillers, spy films, gangster flicks, Westerns, war films, general action flicks, and even horror (Blacula, anyone?)—just with black protagonists who weren’t guaranteed to die in the end. It was even groundbreaking in ways beyond racial—Pam Grier was one of the first, if not the first, of the action heroines. Before Charlize Theron, Scarlett Johansson, Angelina Jolie, and Sigourney Weaver, there was the star of Coffy, Foxy Brown, Friday Foster, and so on.

It was an empowering movement—inspiring to black audiences. And if I may say so, it was a major step towards encouraging true racial equality in society—because it encouraged such equality in pop culture, by having black heroes with the same qualities as on-screen protagonists of old. And Culture is upstream from Politics.

Editor’s Note: In April of 2017 writer Eric M. Blake began a series at Western Free Press naming the “Greatest Conservative Films.” The introduction explaining the rules and indexing all films included in the series can be found here. Liberty Island will feature cross-posts of select essays from the series with the aim of encouraging discussion at this cross-roads of cinematic art with political ideology. (Click here to see the original essay. Check out the previously cross-posted entries on Jackie Brown, Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Unforgiven, Hail, Caesar!, Apocalypse Now, Fight Club, Man of Steel, Batman v. Superman: Dawn Of Justice ULTIMATE EDITION, Wonder Woman, Kill Bill, Gran Torino, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, Blazing Saddles, and The Magnificent Seven.) If you would like join this dialogue please contact us at submissions [@] libertyislandmag.com.

So of course the Jesse Jacksons and Al Sharptons of the world had to smear the movement as “racist”—“promoting stereotypes”, and other such nonsense. After all, if the black community in America were to actually achieveequality in society, the race hustlers would be out of a job.

Here’s a documentary on YouTube about the history of the movement (starring none other than Quentin Tarantino, among others you may know)—and exactly what happened, to bring it to an untimely end. Pay special attention to the discussions about the aftermath. It’s not too far-fetched to say that, had Blaxploitation survived, there’d have been a black winner of Best Actress long before Halle Berry. And in fact, I’ll take it a step further: Remember that “Oscars So White” outcry, last year? I can tell you with honest certainty that the blame for the “racial gap” in Hollywood can be laid solely at the feet of Jackson and Sharpton and the NAACP—and all those who smeared Blaxploitation and scared Hollywood out of providing too many “cool” roles for black actors for years. Unless, of course, they were “safely” paired up with a white “main” protagonist—see: 48 Hours and the Lethal Weapon franchise.

The worst part is: We see that sort of scare tactic thrown around by the Left to this very day. See all the SJW outcries over “cultural appropriation”. Geez, this past week, some guilty gringos even whined and screamed about a taco joint.

But I digress.

It’s worth noting that the directors of many of these movies (including the director of this one, Gordon Parks) were…black. And they clearly didn’t see anything wrong with the movies they made.

Before I go on, here’s a cool factoid: Jim Brown—the football legend who went on to star in quite a few Blaxploitation flicks—made some headlines, last year. You may recall…he praised the heck out of Donald Trump.

Can ya dig it?

Alright—now to Shaft.

WHY IT’S A CONSERVATIVE FILM:

Shaft was famously the second film of the Blaxploitation movement. The first was (wrap your head around this title) Sweat Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. That one you can pretty much infer is a “radical” film, politically…considering how the Black Panthers made it required viewing for their members. At any rate, the film’s plot relies on notions about corrupt white cops and The Man—and a lot of emphasis on a certain…physical stereotype, and all the “virtues” thereof. (I should add: Bill Cosby produced this flick.)

To top it all off, the film’s publicity campaign included the tagline: “Rated X by an all-white jury”. Yeah…okay. All I gotta say to that is: If you fill a film with that kind of sexuality, it probably wouldn’t matter what the jury’s color is.

At any rate, the one thing the film did that people really responded to was: The black protagonist, on the run from everyone, did not die in the end. He got away. And that, more than anything else, was what launched a movement.

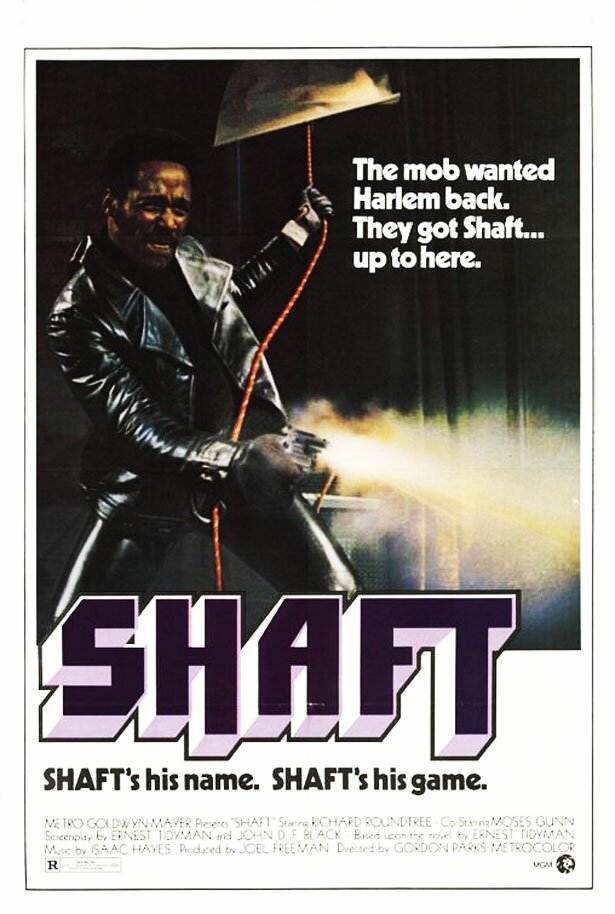

The studios saw the hunger among a potential big audience for what it was—and MGM went right to work to make a mainstream hit with a black hero. The result, of course, was Shaft—co-produced by Stirling Silliphant (of Route 66and In The Heat Of The Night fame), and directed (as I noted above) by Gordon Parks.

But the politics of Shaft and Sweet Sweetback are about as different as night and day—whether people noticed it at the time or not.

“DON’T CALL ME JUDAS”:

When I saw Shaft for the first time, this stuck with me the most. John Shaft is a private eye, doing his best to keep his part of Harlem stable. Easier said than done, caught as he is between the Black Mob ruling Harlem and the Mafia trying to cut in—only kept out by the Black Mob.

Meanwhile, the NYPD wants a handle on the situation…but this is the 1970s. And the Harlem community doesn’t care for white cops.

Shaft’s caught in the middle of all these tensions…and it’s all he can really do to play it cool, and stay as outside the politics of the situation as humanly possible. He’s tight-lipped with the cops over two “Harlem cats” pursuing him—even though one of the cops, Lt. Vic Androzzi, is his friend; but like any good private eye, it’s so he can figure out the situation without interference.

Besides, a lot of his contacts in Harlem don’t like the idea of his getting friendly with white cops—and already, he’s got old friend Ben Buford—now a militant leader with a Malcolm X poster—accusing him of being…a “Tom”. As in Uncle.

Shaft won’t have it—making a point to rebuke Ben for his “revolution” antics and “that Uncle Tom jive”, after someone whacks part of Ben’s crew.

“You think like a white man.”

“And you don’t think at all!”

Meanwhile, Shaft holds black mobsters—like Bumpy, who’s trying to flex muscles against the Mafia—in complete contempt, knowing darn well they’re doing more harm than good to Harlem. And no racial justifications they spew can change that.

While we’re at it, Shaft has quite a few white folks in his network—from a newspaper man, to a private doctor, to a bartender. And, of course, a cop.

A FRIEND ON THE FORCE:

Speaking of Lt. Vic, his dynamic with Shaft is…complicated. They have a great camaraderie—particularly when it’s just the two of them, with no chance of anyone seeing or listening in. They understand each other—and as such, Vic’s sure to vouch for him when the other cops take issue:

“That boy’s got a lot of mouth on him.”

“The ‘boy’s’ man enough to back it up, too.”

“…Gotta lean on that kind!”

“You don’t ‘lean’ on that ‘kind’.”

Vic knows darn well the situation Shaft’s in—and he respects him for trying his best to keep above it. Still, he’s got a job to do, too—so if there’s anything he can tell him….

“You scare me to death, Lieutenant.”

“And you’re buying trouble not only for yourself, but a blood bath up in Harlem—you want that? All I’m asking you is to let me know what’s going on! No names—no places—just what! I’m not asking you to sell out—just…tell me the name of the game, so I know the rules.”

“…I’ll think about it.”

And with a hand slap, it’s fair enough—for now. And Shaft’s all too willing to give Vic what he knows—once he knows enough to be on top of things. As for Vic, he knows how to look the other way, so Shaft can do his thing.

FOR BONUS POINTS:

Probably because the customer is Shaft, no one apparently felt any qualms about the black shoe-shiner in the film’s opening. Of course, P.C. or no P.C., the man’s a part of Shaft’s network, giving him info on the two men looking for the detective. Besides, it clearly transcends a racial stereotype here—where the character’s clearly given basic human dignity.

Bumpy calls out Ben Buford when the latter lashes out about Bumpy’s “pimping”—telling him his militancy is a con job, too. “It’s all the same game”—the difference is, Bumpy admits it. And “noble” as Buford is…he relents to helping out, for $10,000 a head.

WHY IT’S A GREAT FILM:

All right, all right…you know you know the first reason:

There’s more, of course—but let’s dwell a little bit on that opening sequence, set to that classic Isaac Hayes theme. Like any good introduction to the hero, we get a good feel to what kind of man he is. One of the first things we see him do is jaywalk—because let’s be honest: that’s the best he can do with New York City traffic. So he’s a pragmatist who’s not above pushing the limits of the law as he needs to. He snaps at and flips off a taxi driver who takes issue with it—he’s a “tough guy” who doesn’t apologize for doing what he’s gotta do.

When a hustler offers to sell a watch, Shaft flashes his badge, scaring the guy off—he’s a lawman, and uses the law when he can. When he walks by some sign-carriers—some protesting, some advertising for The New York Times (a former newspaper), he looks at them in amusement before shaking his head—he’s got no time for people trying to call attention to themselves, either way.

And that’s all before the lyrics extol our brother’s sense of loyalty, bravery, and romance—followed by a nice moment with a blind white newspaper seller who’s presumably part of Shaft’s “network”. Tipped off by the guy about some shady characters looking for him, Shaft is sure to keep watch—hiding back and peering for a moment, before heading off. He’s properly paranoid. He has to be. He’s a private eye.

HARLEM NOIR:

In addition to being one of the “kickoff” films of the Blaxploitation movement, Shaft was also part of the trend of “neo-noirs” exploding onto the scene in the 1970s—a Second Wave of Film Noir, re-interpreting the classic stories with a new spin, fitting new trends in urban life. Cities of the 1970s had a new and different kind of “dirty”—and with it, a new kind of “cool”. The most memorable of these neo-noirs included Taxi Driver, The French Connection, Chinatown (set albeit in the 1930s), and so on—extending into later decades, of course, with Body Heat, L.A. Confidential, Basic Instinct, Fatal Attraction, Sin City, etc.

Shaft is no exception. What you have here is a basic “private eye” storyline. Shaft starts out with a “routine” kidnapping case—that leads to him getting caught in the crossfire between rival criminal gangs. He’s got a friend on the force, with whom he has a…complicated dynamic. His code of honor and professionalism demands he not give up his client, even to the police—and besides, someone in the force might be on the take.

It’s just channeled through black sensibilities—he’s black, the cops are white, and the crossfire’s between the Mafia and the Black Mob. It’s a reconstruction of Hammett and Chandler, with a new racial context:

“Man…I tell ya, down these mean streets a brother’s gotta go. Thing is—he ain’t mean himself, tarnished nor afraid.

“Can ya dig it?”

RICHARD ROUNDTREE AS SHAFT:

Roundtree bring the calm collected “cool” required of a private eye—adding the right amount of casual “chill”, to bring a new spin on it. Meanwhile, he speaks the typical “funky” sort of slang expected in Blaxploitation, but in an understated sort of way, so it sounds natural, only rarely calling attention to itself (his use of “cats”). You can feel he’s in his own sort of world—complete, his own man…made all the more apparent amid all the groups around him. And his moments of unspoken understanding with Vic are superb—as are the moments they share a chuckle.

BY THE WAY:

In the opening sequence, the movie theater marquis announces The Scalphunters, a Western starring Burt Lancaster as a fur trapper who finds himself paired up with a black (former) slave, which begins a string of misadventures made worse by the trapper’s refusal to see the freeman as an equal.

The film inspired two lesser-known sequels—Shaft’s Big Score, which continued the “Harlem Noir” motif, and Shaft In Africa, which put Shaft in a James-Bond-esque scenario (to his verbal amusement). Years later, a new Shaft came out starring Samuel L. Jackson. For much of the film, we assume it’s pretty much a remake…until Richard Roundtree shows up, as the original John Shaft—the uncle of Jackson’s Shaft.

Fans of the original Star Trek should recognize one of the screenwriters: John D. F. Black, who helped write many of the best episodes.

Finally, this film may or may not be the source of Han Solo’s legendary “I know.” Shaft pulls it on his girlfriend over the phone.

Buy this classic of the Blaxploitation movement here. And stay film-friendly, my friends.

Comments

Leave a Reply