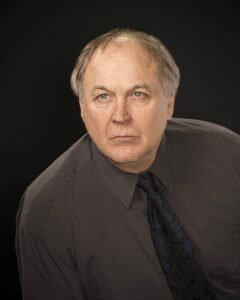

It was 2002, and our guru at the weekend writing workshop on the Oregon coast was author James Frey.

Not that James Frey, who got in big trouble with Oprah Winfrey after committing one of literature’s cardinal sins: adding fictionalized elements to a purported memoir.

Our James Frey, James N. Frey, was (and is) a recognized author of both fiction (with an emphasis on mysteries) and nonfiction. He earned an Edgar Award nomination for his 1987 novel Long Way to Die, and his 1992 novel Winter of the Wolves was a Literary Guild Selection. By the second year of the new millennium, our Frey was perhaps best known for his writer’s how-to book, How to Write a Damn Good Novel. Frey was a much sought-after commodity for writer’s groups looking for workshop leaders and literary mentors interested in sharing knowledge of story-craft and developmental structure with aspiring and early-stage professional writers.

Twenty such writers had each ponied up $300, and on a foggy Friday night convened at the Oregon Writer’s Colony retreat at Rockaway Beach to cook communal meals, read aloud excerpts of their work, and face the legendary, brutally honest, and potentially devastating critiques of Mr. Frey.

Our guru was known for pulling no punches when assessing a writer’s work.

On the large wood mantel that dominated the living room of the vintage home was carved the famous Latin quotation every writer need take to heart when hope of publishing success seems lost: Illegitimi non carborundum (Don’t let the bastards get you down).

*

They were (and still are) called Frey Intensives. Over the course of approximately 48 hours, intensive critique sessions drill down on twenty manuscripts, pinpointing writing weaknesses, severing attachments to momentum-killing darlings, and disabusing writers of counterproductive delusions about the level of their work. Of particular interest to Frey and workshop co-teacher Barbara McHugh is the first pages of novels. As everybody who writes and hopes to be legitimately published knows, the gatekeepers in the publishing industry are inundated with manuscript submissions. If they bother with unsolicited submissions at all, their interns or assistant editorial readers are trained to summarily reject novels whose opening pages betray fundamental problems.

It was my first Intensive, but several of my bunkmates had undergone the rigors of Frey’s unsparing critiques before. Their description of the experience for the edification of a first -timer was a mix of compassionate concern and gleefully harbored sadism. This was not going to be your friendly, supportive community college creative writing class critique group. If a writer couldn’t handle the unvarnished truth about his or her work, a Frey Intensive might be something best put off till a later date.

Intensive meltdown stories had become part of the mystique. Stories of female writers who had wept after hearing Frey’s verdict on their beginnings. Male writers who had gotten huffy and told Frey he didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about. And flips on these emotive gender stereotypes, men who cried, and woman who got good and damn mad. There were stories about writers who had left Rockaway house after a Frey critique, in the direction of the pounding surf presumably, and never returned.

There were just as many positive anecdotes from writers who’d taken Frey’s medicine and made it work for them. (Frey’s website has several such testimonials). There was the story about the woman whose opening pages had been blithely dismissed by Frey at one of the weekend retreats, who had gone on to have the very novel Frey criticized published by one of the major publishing houses. The author in question received good reviews for the book, a coming of age novel, and had been subsequently green-lit to write a sequel.

Part of the lore surrounding this episode was that the writer who’d gone on to success had written Frey a courteous, professionally crafted letter, thanking him for being so hard on her, but also wryly reminding him that the work he’d criticized had broken through.

I was about to find out exactly what everyone who’d ever had their first pages dressed down by James N. Frey was talking about.

*

The mental effort to keep up with the ongoing analysis of my fellow writers’ excerpts was taking a toll. Viewing a white-capped Pacific out the back window during breakfast was restful and renewing, but soon enough the circle would gather and my compadres would gird for their turn in the spotlight. Our 20-page novel openings had been delivered to co-teacher McHugh a week before the workshop. When a writer’s turn came, he or she would read the excerpt aloud in front of the group.

Then the room would fall silent, everyone waiting for Frey’s comments.

A man had written a post-apocalyptic novel: thumbs down, obtuse prologue and too much backstory in the opening pages. A woman had written a novel about a woman trying to pick up the pieces after a divorce: sorry, reject, information dump alert. A gay writer had written about his father’s descent into Alzheimer’s: pass from Frey, stakes for protagonist nonexistent in opening passages. Even writing liberal for a veritable collection of liberals did not move the needle of assessment. A woman had written a novel about how evil bigots led by a Rush Limbaugh-like talk show host were threatening to take over America: Frey didn’t buy it.

After Frey weighed in, workshop participants were given the opportunity to expand on what they’d heard, offer kinder, gentler suggestions for fixes, or even positive notes about things they’d liked. But no one substantially disagreed with Frey’s overarching take about inherent problems.

On and on the readings went, with breaks for meals and private writing sessions during which writers would take the feedback they’d received and brainstorm how they would solve problems, fix things, start over. On Sunday morning, we learned that one of the writers in the group had risen before dawn, talked briefly to the woman she shared a bedroom with, packed up and returned to Portland.

“Was she all right?” asked Frey.

The answer came in the flat-effect tone we were coached to read our pages in, “Yes.”

As the weekend drew to its final hours, with sunbreaks finally showing on the surface of a brooding gray sea (see below), it seemed Frey had liked little that he’d heard. Work that sounded fine to me was repeatedly somehow and some way found not up to snuff. I felt for my fellow writers, none of whom had gotten a sterling review.

My thoughts turned worrisomely to the fate of my own manuscript as my turn to read approached. I had discerned two definite literary elements that Frey had little patience for: prologues and weather reports. My novel had a prologue with lots of weather, but my opening pages problem turned out to be worse than that. After my weather-heavy prologue, the novel opened with a teenager opening an old chest and finding some yellowed news clippings that revealed a story about his paternal grandparents that has been kept secret from him. As I read, remembering to breathe so I could get the words out, I knew that I’d learned enough to know that the beginning of my story would garner an auto-reject from James N. Frey.

The weird thing was, the really devastating thing was, that Frey didn’t say much of anything about my excerpt. He just muttered some platitudinal advisories and moved to the next writer. I was left with the impression that my work was so lousy that even the brutally honest Frey was moved to spare me the ordeal of being cut to ribbons in front of the group.

Frey’s assistant found me later and gave me the lowdown that Frey (in an uncharacteristic moment of compassion?) had withheld: “There’s no conflict in your opening pages, just a lot of weather and your protagonist ruminating.”

She was right.

After our final meal together, Frey took his place near Rockaway’s portentously-inscribed mantel to bid farewell to attendees. My sense as I stood before him was that he didn’t think I was far enough along in my literary journey to have been included in such a select group. I was surprised when he gave me a firm handshake.

“Hope to see you next time,” he said, making eye contact and smiling as if I was a wordsmith worthy of respect.

*

My companion on the drive to the coast was the man whose post-apocalyptic novel opening had failed to impress, and we ruminated on the ride home.

“Well,” said the writer, a dear friend, who had hung his dreams on a story about a terrorist nuclear bomb obliterating the Portland Metropolitan Area, resulting in a society that is, if I remember correctly, set back to the Bronze Age.

“It’s like the saying carved into the mantel, right?”

But the Frey Intensive hadn’t got me down. I knew that after a couple of days detox I’d be ready to jump back into my manuscript. Ready to find a new starting point, to further develop my own voice and style, and to hone the skill it takes to sustain conflict and keep readers turning pages. I was also gestating a new appreciation for editors and mentors who help writers make the most of both their God-given talent and hard-earned mastery of craft.

***

Photo by rawpixel.com

Comments