I can see myself, standing in a local video rental store, circa 1995, holding a hard plastic covered copy of The Remains of the Day and thinking, “How badly do I want to see this movie?”

I knew it was a critical hit, having been nominated for eight Academy Awards, but I knew little of the story besides what I gleaned from the cover and read in the back synopsis. In the end, I decided, multiple times as it turns out, to put it back on the shelf. Renting it would have been a commitment. I had to pay for it, lug it home, pop it in the VCR, rewind it when I was done, and shuffle my schedule around to return it to the store.

With a streaming service, there is no commitment. Simply swipe, tap, and watch as much, or as little, as you like. No rewinding necessary. And so it was under these, much more favorable conditions, that I watched this twenty-eight year old film for the first time.

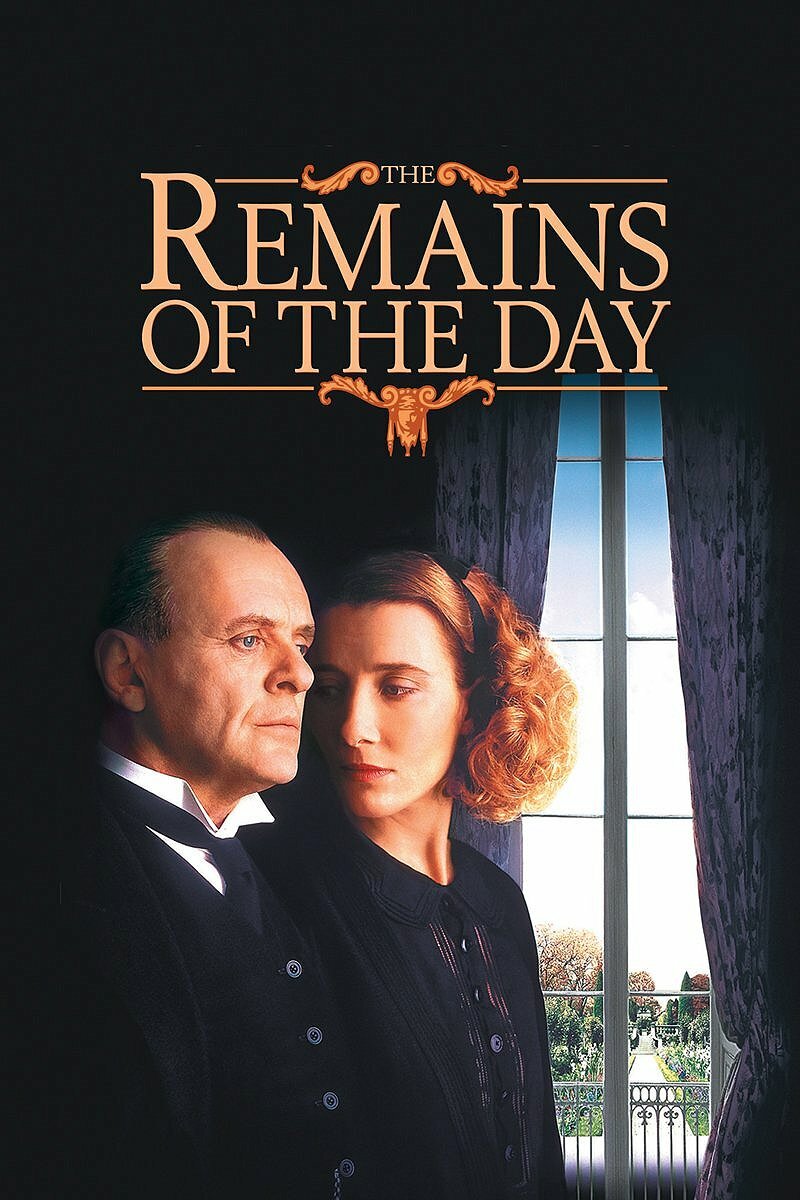

It turns out I made the right decision all those years ago. At that tender age I don’t believe I would have appreciated Anthony Hopkins’ incredibly delicate portrayal of Mr. Stevens, the butler of Darlington Hall. Nor would I have had the same understanding of his relationship with Miss Kenton, the housekeeper brought to life by Emma Thompson. And I would have completely missed the nuances of the subplot involving Lord Darlington, who sympathizes with the people of interwar Germany, and attempts to broker an appeasement deal between British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Hitler’s German ambassador.

Lord Darlington’s conduct is derided by characters large and small. An impossibly young Hugh Grant, playing a journalist friend of Darlington, takes a few swipes at him. So does a random passerby who offers Mr. Stevens a lift. Christopher Reeves, in one of his last appearances before his tragic riding accident, gives a rousing speech denouncing Darlington’s attempt to appease Germany, calling him an “amateur.”

The audience is, collectively, expected to nod their heads in agreement to all this, and why not? Nazis are vile, despicable creatures. Anyone who attempted to appease them, even before the full extent of their crimes against humanity were made known, shares some culpability for those crimes, do they not? This is brave art. Truth telling art. Art that shines a light on the human condition, exposing something deep within us we don’t want to see.

Or is it?

With the benefit of forty-eight years of hindsight, in 1993 it was easy to say, as the film does, that Chamberlain’s late 1930s policy of appeasement falls somewhere on the spectrum between folly and sin. What the movie fails to mention, however, is, at the time, the policy was quite popular.

Germany’s oppression of its Jewish people, the movie suggests in multiple scenes, should have been enough to persuade those inclined toward appeasement to turn against Hitler. Principles — like dignity, the movie hammers home again and again — should take precedence over other considerations.

Would that this were true.

Principles require commitment. If you don’t want to rewind and return the movie, don’t take it home from the store. You must be willing to stand alone with your beliefs when everyone else is following the flow. Hollywood doesn’t do that.

It’s one thing for the industry to portray the most hated political movement of all time – Nazism – in a negative light. It’s quite another to criticize a popular, lucrative regime doing Nazi-like things today. Can you imagine a remake of The Remains of the Day with oppressed Uyghurs replacing the Jews, and members of the Chinese Communist Party replacing the Nazis? I can’t. It would be the correct stand to take. It would be the principled stand to take. But it would also negatively affect the bottom line of whatever studio chose to make the stand, which is why it will never, ever happen until it’s too late to matter.

“Never again,” the slogan used by prisoners liberated from the Buchenwald concentration camp, has been repeated far and wide in the three-quarters of a century since as an entreaty against genocide. You can almost hear the phrase dripping from the lips of the righteous characters in this film. Never again should we allow the oppression of any people by a government. Never again should we allow people to be herded into concentration camps. Never again should we turn a blind eye to those who practice racism or genocide. Art says these things, Hollywood says these things, actors say these things, but nobody believes them.

We ignored the genocide in Rwanda, shortly after this movie was made. No one much cared when Saddam Hussein attempted to exterminate the Kurds of Northern Iraq. As the genocide in Darfur unfolded, we were occupied with other things. And now that there are widespread reports of over a million Uyghurs locked up in concentration camps, the world is too consumed with figuring out how to grab a larger share of the Chinese consumer market. Never again, indeed.

What, then, after twenty-eight years, remains of The Remains of the Day? Nothing, except the performance of a lifetime from Anthony Hopkins, and a slew of meaningless platitudes designed to make us feel better about our history while we watch it repeat itself in the present day.

Comments

Leave a Reply