Some weeks ago, before the lock-down became tortuous, my beautiful niece asked me to write her a short story about a man who is left at the altar by the love of his life. She was turning twenty and this was the present that she wanted from me. Maria and I have played these literary games since she was a teenager. I love the fact that though she is a child of her time, and fully conversant with social media, she also likes to read and write.

The short story was an opportunity to play with a plot I have been imagining for sometime: a somewhat lonely, young courtroom artist who gets involved with a woman that he paints during a trial. I have thought of doing a novel where the woman is involved with a drug-smuggling gang. For Maria’s short story, however, I made her an actress in a sexual abuse case. It was a short story and therefore difficult to build up the sense that the actress was truly the love of his life. So I brought in a device, based on an observation Milan Kundera had made in Unbearable Lightness of Beingthat I had always found intriguing. It was the sort of comment that could never be made today, because it rang so true. Kundera had said that there were two types of men, the epic lover and the misogynist, Don Juan and Tristan. Don Juan loved all women and had trouble distinguishing one from the other. The misogynist was indifferent to all women because he could only love one.

Kundera was a hero of mine for that precise understanding of humanity and the courage to tell it. Then I remembered that he had been the co-author of a recent ridiculous open letter in defense of the European Union, along with Salman Rushdie, Bernard Henri Levy, and two dozen others. Written in January 2019, a few weeks ahead of the EU parliamentary elections, the letter proclaims:

Our faith is in the great idea that we inherited, which we believe to have been the one force powerful enough to lift Europe’s peoples above themselves and their warring past. We believe it remains the one force today virtuous enough to ward of the new signs of totalitarianism that drag in their wake the old miseries of the dark ages. What is at stake forbids us from giving up.

One wishes that the authors cared more about the fate of prose than the fate of Europe. This was the best that the greatest novelists of our age could come up with? Purple, pastiche, pretentious, pompous, paranoid.

Kundera of all of them, I thought, would have avoided associating himself with this. I could imagine him writing sarcastically about the effort as he wrote mockingly, in Unbearable Lightness, of the group of doctors, actors, activists who went to the Cambodian border from Thailand to protest the American bombing.

A well-known American photographer, having trouble squeezing both their faces and the flag into his viewfinder because the pole was so long, moved back a few steps into the ricefield. And so it happened that he stepped on a mine. An explosion rang out, and his body, ripped to pieces, went flying through the air, raining a shower of blood on European intellectuals.

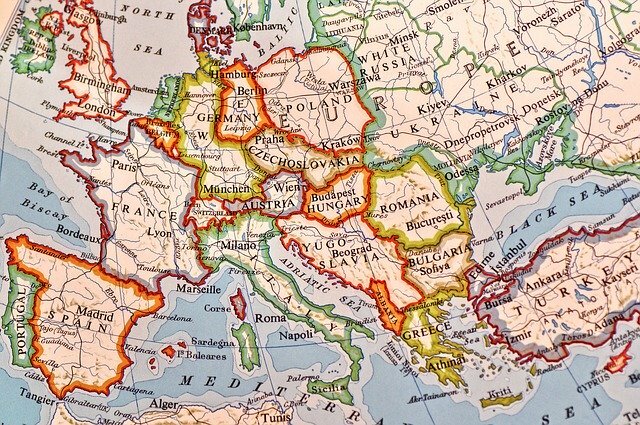

The cartoon violence of this episode stands out starkly from the contemplative narrative of the rest of the novel that you can’t help but think that Kundera had some sort of resentment against European intellectuals. He had good reasons for that. In 1984 he wrote an article for the New York Review of Books, “The Tragedy of Europe”. The real tragedy of Central Europe, he argues, is not its enfoldment into the Soviet sphere but its abandonment by the West. Then he prophetically put his finger on the tragedy of the West. The Medieval era in which Europe shared a common religion gave way to the modern era “in which the Medieval god has been changed into a Deus Absconditus, religion bowed out giving way to culture, which became the expression of the supreme values by which European humanity understood itself.” In 1984 he argued that an equally important change was taking place: culture in turn was giving way. “But to what and to whom?” he asked. “What realm of supreme values will be capable of uniting Europe? Technical feats? The marketplace? The mass media?” He provides no answer.

When Hungary was invaded by Soviet forces in 1956, Kundera writes that the head of the Hungarian News Agency sent a telex to “the entire world” that “we are going to die for Hungary and for Europe.” With pathos Kundera continues: “Behind the Iron Curtain he did not suspect that the times had changed and that in Europe itself Europe was no longer experienced as a value.” Now that Europe means less and less I find it strange that Kundera has embraced it. I prefer to imagine him as one of his characters: refusing to sign this ridiculous letter, if only because it is so terribly written.

My niece liked her story very much.

****

Photo by MabelAmber (Pixabay)

Comments

Leave a Reply