For the past month, I have been diving into some of the Golden Age Horror films from the 1930s. Like most people, these are movies that have always been in the background of my cultural knowledge, but ones that I have never actually seen. I decided to change that this October, so I watched Dracula, Frankenstein, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Like a lot of older films, they can be slow and somewhat hokey at times. Since these were some of the first sound films ever produced, most of the actors came right from the stage to the screen, and it shows. As anyone who has been in acting knows, you have to overact on a stage production in a way that comes off as silly in a film, but since many of these actors were not used to the transition, a lot of the performances come off as overdone.

But none of that can suppress the genuinely great scenes in these films; indeed, they deserve the bone-chilling reputation that they have garnered over the decades. No one can ever forget Lugosi’s haunting performance as the title character of Dracula, Fredric March’s leering grin as Mr. Hyde, or Colin Clive’s electrifying screams of “It’s alive! It’s alive!” as the horrifying creature comes to life.

But I want to touch on an interesting aspect in two of these films, Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Both movies are an implicit criticism of man’s faith in science, specifically science’s capability of solving mankind’s two perennial problems: death and evil.

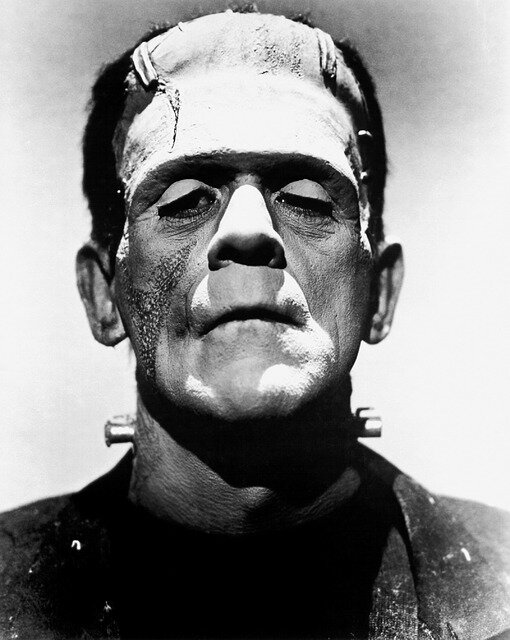

In Frankenstein, released in 1931 and directed by James Whale, Dr. Frankenstein successfully brings a living being assembled out of different corpses to life. “It’s alive, it’s alive!” He shouts, gloating to the heavens over his success. “In the name of God, now I know what it is to be God!” This apparent triumph, however, becomes a disaster as the monster (brilliantly portrayed by Boris Karloff) murders Frankenstein’s professor and accidentally kills an innocent young girl before he himself is killed by an angry mob of villagers.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, also released in 1931 and directed by Rouben Mamoulian, takes an even darker route. In one of the film’s earlier scenes, the ambitious yet naive Dr. Jekyll explains to his colleagues his belief that the soul of man is divided into two selves; one good and one evil. “If these two selves could be separated from each other,” Dr. Jekyll explains, “how much freer the good in us would be… And the so-called evil, once liberated, would fulfill itself and trouble us no more.” The Doctor creates a chemical that separates these two selves from each other, and his vile alter-ego, Mr. Hyde, is born. Despite the Doctor’s best intentions, his evil side is anything but suppressed, as Hyde proceeds to sexually and psychologically abuse a bar singer named Ivy Pierson, proceeding to murder her in the film’s climax (and who ever said black and white films were tame?).

Now of course, none of these films are particularly scary by today’s standards. The rape scenes in Jekyll are only strongly implied in the film, and the camera always cuts away before anything too graphic happens. The movies contain hardly any blood or gore, and there are not really any jump scares. But it is the central themes of these films which endure. Both feature a protagonist with an overconfidence in the power of science, and whose attempts to solve the perennial human limits of sin and death through their own efforts only leads to destruction. Fredric March’s portrayal of Dr. Jekyll as a man naive to humanity’s capacity for evil especially captures this attitude. In one of the films most important scenes, Dr. Jekyll’s friend, Lanyon, warns him that Jekyll’s experiments in eradicating human evil are crossing bounds that science could not cross. “I tell you, there are no bounds,” Jekyll haughtily replies, before pointing to the gas lamps that light London’s Victorian streets. “Look at that gas lamp. But for some man’s curiosity, we shouldn’t have had it… One day, London will glow with incandescence… it’s in the byways that the secrets and wonders lie, in science and in life.”

After Jekyll’s alter ego murders a bar singer in cold blood, the doctor is singing a completely different tune. Remorseful for what he has done, he realizes that conquering the dark corners of man’s heart is a little more complicated than extracting a tooth. “I saw a light, but I could not see where it was leading.” Jekyll cries out to God in a dramatic moment. “I have trespassed on your domain. I’ve gone further than man should go.”

It is important to realize the historical context in which Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were made, both the films and the original novels the directors based them on. Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, was one of the leading voices of Romanticism, a literary movement that was skeptical of the Enlightenment’s faith in scientific progress. Many critics take Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as an implicit criticism of Victorian mores and Victorian England’s sense of its own superiority.

Many of the actors and directors associated with the film adaption of these novels survived World War I. James Whale, the director of Frankenstein, was taken prisoner during the fighting, while Fredric March served in the US army during the conflict. As many film critics and cultural historians have pointed out, the surge of monster movies in Europe and America in the twenties and thirties can be seen as a reaction to the horrors of that war. We should not be surprised that, coming out of a war that was marked by new technologies that could kill on an unprecedented scale, the directors and actors involved in these movies would have a newfound suspicion of the scientific and technological progress Europe had made in the preceding century.

And now, in our own age, as genetic manipulation and Artificial Intelligence move off the screen and into our daily lives, perhaps we should be wary of believing that only unmitigated good can come out of these new developments. Perhaps, in the wise words of Dr. Lanyon, we should understand “that no man [can] violate the traditions of his kind and not be damned.”

Otherwise, we could create a future that will become a horror movie of its own.

Comments

Leave a Reply