“Señor Chance, this is my hotel. And you are a guest under my roof. And I will not be told what I shall do, and what I shall not do, señor.”

WHY IT’S A CONSERVATIVE FILM:

Where to begin?

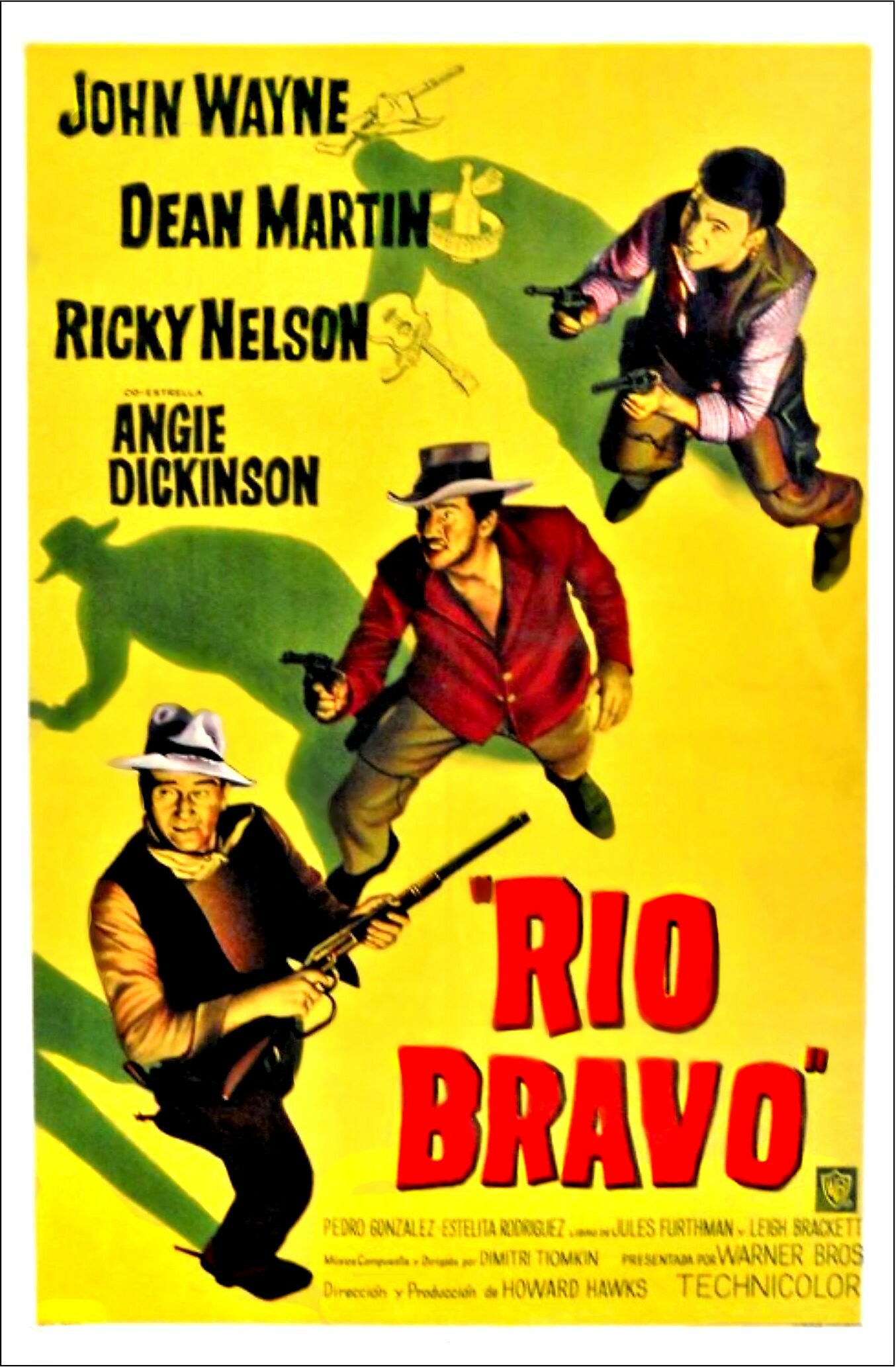

To be perfectly honest, if I had taken the time to go the “Countdown” route for this series, I’d say this film would have been a serious contender for #1. Rio Bravo is one of the great success stories of Conservative Cinema—if for no other reason than this: It is the definitive golden example of an intentionally Conservative film, made specificallyby Conservatives, with a conscious Conservative agenda…that became a masterpiece. If anyone ever doubts that Conservatives can make and have made great art—and great movies in particular—here is the film to point to, where said critics have no excuse.

With that in mind, it’s important to look at why this Western classic was made, arguably even more so than analyzing it “as a film unto itself”. And to do, so, I have to begin with a sincere apology to the great Bill Whittle, who has long championed High Noon as one of his all-time favorite movies. You see…

Editor’s Note: In April of 2017 writer Eric M. Blake began a series at Western Free Press naming the “Greatest Conservative Films.” The introduction explaining the rules and indexing all films included in the series can be found here. Liberty Island will feature cross-posts of select essays from the series with the aim of encouraging discussion at this cross-roads of cinematic art with political ideology. (Click here to see the original essay. Check out the previously cross-posted entries on Jackie Brown, Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Unforgiven, Hail, Caesar!, Apocalypse Now, Fight Club, Man of Steel, Batman v. Superman: Dawn Of Justice ULTIMATE EDITION, Wonder Woman, Kill Bill, Gran Torino, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, and Blazing Saddles.) If you would like join this dialogue please contact us at submissions [@] libertyislandmag.com.

SHOWDOWN AT HIGH NOON

John Wayne had originally been offered the role of Marshal Will Kane (which then went to Gary Cooper), the protagonist of Fred Zinneman’s High Noon. The Duke read the script—written, incidentally, by the far-Left Carl Foreman (more on him later)—and promptly turned it down. Now, much as I would’ve loved to see the rough, quintessentially macho, bigger-than-life John Wayne paired up with the sweet, refined, and elegantly feminine Grace Kelly—the truth is, I understand why he walked away.

For you see, High Noon is a Left-wing film—more than that, a militantly Left-wing attack on small-town America, smearing the average American en masse as a hypocritical coward who’d rather turn their back on a hero who needs them than help out, for a long variety of reasons.

More than that, like so many Leftist smears, it just doesn’t make any sense. Yes, we can point to the Kitty Genovese incident—and more contemporary counterparts where people Just Didn’t Want To Get Involved…but that’s nowadays—after the Left has so deeply corrupted our culture, and poisoned the idea of classical masculinity and private-citizen heroism as something to avoid. The whole gun control argument—“Run and hide, and let the cops take care of it…while people die as we wait for them….”

In the meantime, the America of back then didn’t deserve such a smear—let alone the America of the Old West. As John Wayne himself later put it, explaining just why he’d hated High Noon so much:

“A whole city of people that have come across the plains, and suffered all kinds of hardships, are suddenly afraid to help out a sheriff, because three men are coming into town that are tough? …Then, at the end of the picture, [Will Kane] took the United States marshal badge, threw it down, stepped on it, and walked off! I think those things are just a little bit un-American. …Do they strike you as being a true picture of the pioneer West? Or a picture of what Carl Foreman or somebody would like to give our children the impression?”

Further, as Price’s Conservative Guide To Films notes, Marshal Kane “also was meant to be seen as risking his life pointlessly because the townspeople, who represent average Americans, are shown to be cynical, hypocritical, and cowardly. They are not worth defending, nor do they want his help. …The message Foreman hoped to impart from this was that there is no place for heroism in Cold-War America and that the American public was not worth defending.”

So what about Carl Foreman?

Well, he was one of the most famous of the Far Lefties who clashed against the House Un-American Activities Committee. That’s right. He wasn’t one of the original Hollywood Ten…but still, Foreman’s one of the most famous targets of the Blacklist. And incidentally: his screenplay to High Noon was the last thing he wrote and sold before getting forced to follow Trumbo and company “underground”.

That is why he wrote the screenplay the way he did. To Foreman, he—and the other soon-to-be blacklistees—were the lone heroes, forced to “stand alone” because everyone around them “abandoned” them to suffer the “evil” of having to work under assumed names. And so, as his big “(bleep) You, America” before going underground, he wrote what basically amounted to a revenge piece, where Americans are weak and cowardly, and the ideals of the West—and the nation itself—are deconstructed and presented as hollow and false. And for the most part, he got away with it—to this very day.

Well, John Wayne hated it…and so did Howard Hawks.

THE GREY FOX

Howard Hawks is sometimes called “the greatest filmmaker you’ve never heard of”. Frankly, I’d imagine barely anyone today would know his name, were it not for his two biggest living fans—filmmaking legends John Carpenter and Quentin Tarantino. Amusingly enough, the film scholars most responsible for “The Grey Fox” enjoying any respectability among the critical community were the critics-turned-filmmakers of the French New Wave.

The French!

At any rate, Hawks famously took on pretty much every genre that existed in Classical Hollywood—from gangster flicks to war films, from sci-fi (sci-fi horror, no less!) to musical, from sports flicks to sword-and-sandle epics. In the 1930s, he was the undisputed master of the romantic comedy, with Bringing Up Baby, Twentieth Century, and His Girl Friday. (Friday, by the way, is often credited with helping shape a certainly legendary heroine by the name of Lois Lane.)

Beyond all that, he brought us the original Scarface (Yes, the Al Pacino version is actually a remake!) and The Thing(Told you John Carpenter was a fan!). Hawks also directed Sgt. York, the Humphrey Bogart classics To Have And Have Not (which introduced Bogie to his soon-to-be wife, Lauren Bacall) and The Big Sleep…and most importantly to the current subject, Red River.

That Western was Hawks’s first in the genre—and his first project with John Wayne. Famously, The Duke’s performance in that film (the closest he ever came to playing the villain, by the way) caused none other than John Ford—the guy who’d made Wayne a star in the first place—to remark, “I didn’t know the big son of a gun could act!” (Only he didn’t say “gun”.)

And incidentally…Howard Hawks, like John Wayne, was a Conservative. And as it turned out, he hated High Noon, too—albeit for a somewhat different reason. Wayne, again, disliked how the film portrayed average Americans. Hawk’s problem was just how unprofessional Marshal Kane was—going around “like a chicken”, asking rank amateurs to help him do his job. (As Hawks put it, about the only redeeming quality of the movie was Dimitri Tiomkin’s beautiful score—including that immortal, tear-jerking theme, “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling”.)

And so…Wayne’s and Hawks’s solution was something Conservatives today ought to take note about. We often complain about how Hollywood ruins a potentially great film, by shoving in garbage so as to promote their agenda.

Question: “So…what would you have done, differently?”

Answer: “Well…I would’ve done X, Y, and Z.”

“Okay…. I dare you to do it!”

The Grey Fox and The Duke took the dare. And the result was Rio Bravo—the Conservative Alternative to High Noon, and incidentally one of the greatest Westerns ever made.

STANDING ALONE BY CHOICE

Here, the threat isn’t just three or four guys. It’s a whole force of bad guys—hit men hired by a corrupt rancher, Nathan Burdett (John Russell), who’s set off because his brother Joe (Claude Akins) was just put in jail for murder. The town’s held under siege by the hit men…and this time, the townspeople want to help Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne), any way they can—as indicated by Carlos Robante (Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez), the Hispanic hotel owner who makes up for his shortness with his spirit (see the page quote above), and his spicy wife Consuela (Estelita Rodriguez).

(That’s right: To anyone claiming that Conservatives are racist and anti-Hispanic—Hawks counted a Latino couple amongst the heroes in this film. These are apparently Mexican folks who willingly assimilated into American society, succeeding as business owners, running their own hotel…counting the sheriff as a close friend.)

Arms merchant Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond) also wants to help—and goes around rallying people to support the sheriff—even offering help from his own crew. Until, that is, Chance pulls the plug on Wheeler’s efforts, explaining:

“Look, anybody that sides in with me right now’s liable to find themselves up to their ears in trouble. …Suppose I got ‘em, what’d I have? Some well-meaning amateurs—most of them worried about their wives and kids. Burdett has 30 or 40 men, all professionals. Only thing they’re worried about is: earning their pay. No, Pat. All I’d be doing is giving ‘em more targets to shoot at. Lot of people would get hurt. Joe Burdett isn’t worth it. He isn’t worth one of those who’d get killed.”

(By the way…as Wheeler notes, Chance’s power team consists of “a game-legged old man, and a drunk”. In High Noon, guess who does offer to help Marshal Kane—only to be turned down…?)

“WHERE MEN ARE MEN…”

More material for Conservatives to love is how Rio Bravo approaches issues of men—and women. Some time ago, I looked at the Western genre in detail for my “Culture Current” series. There, I pointed out how one of the central themes of the genre is: “What does it mean to be a Real Man?”

As Quentin Tarantino’s pointed out, that theme of “being a man” was absolutely central to Howard Hawk’s body of work—Westerns or no. His favorite subject matter seems to have been, in particular, “men’s fellowship”.

Thus, oftentimes we see the male heroes in his films come in groups—groups of individuals, who come together “as men”—devoted to their work, and to their own integrity. They build each other up when down, and call each other out when need be. “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do”—and to Hawks, that often means forming a power team of men, guiding each other without providing crutches. Each has their strengths, and each has their weaknesses. They’re all people—and they’re all men, Real Men. It’s “male bonding” in the best sense of the word: What it entails, and how vital it is to a man’s emotional growth.

NOW, AS FOR THE LADIES…

Whoever thinks Conservatism and the concept of women’s empowerment are somehow at odds should take a good look at the character type called the “Hawksian Woman”. Essentially, folks, Howard Hawks was feminist before feminism was “cool”. And like so many Conservative feminists, he was later accused of misogyny. But I digress.

The truth is, it’s been a running gag, these past several years, about how badly so many filmmakers botch up the notion of a “strong female character”. It gets pretty comical, honestly. Filmmakers keep falling into one of two traps:

- They fill their screenplays with dialogue about how smart/capable a heroine is, only to never show it; OR

- They create invincible, invulnerable “super-chicks” who can somehow beat the crap out of giant tough guys despite being model-thin…or else, in the absence of “action”, they’re the only intelligent person in a room full of dumb guys (who somehow got the title of “scientists” or whatever). Either way, she’ll round about never make a mistake. Flaws are “demeaning”, you see—and so, by the way, is vulnerability.

It’s a sad pattern, but a predictable one from Lefties who refuse to accept some obvious truths about human nature. Men and women are different—and there is value to be found in those differences, in what we shouldn’t be afraid to call “masculinity” and “femininity”. “Femininity” and “strength” are not mutually exclusive, because “femininity” is not, in fact, a construct of the “patriarchy” boogeyman, to “keep women down”. Just the opposite. As a rule, it’s the pseudo-feminists with chips on their shoulder about such things that are the biggest weaklings of all.

The truth is, 3rd-Wave Feminism has done more to keep women down than anything else in society, today—and until Hollywood realizes that, we’ll continue to see failure after failure, regarding “strong female characters”.

Thus, leave it to Howard Hawks, Conservative, to create the quintessential archetype for a true “strong female character”. And frankly, no one should be surprised: Because a Conservative knows to proclaim “vive la différence”, he or she can explore that difference, and the benefits thereof, without any sense of irony or guilt.

The Hawksian Woman is quite sexy, to be sure—as played by iconic Hollywood sirens ranging from Katherine Hepburn to Barbara Stanwyck to Lauren Bacall to Marilyn Monroe. (Trivia note: You know that classic of Marilyn’s, “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend”? It comes from the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Guess who directed it…!) But she truly is intelligent, too…psychologically so. And the way Hawks and company craft her, the two qualities go hand in hand.

The Hawksian Woman holds her own—she’s confident, and she’s cool. She can and often does go toe-to-toe with the main hero, keeping up with him in a verbal joust that’s clearly a game played partly for the fun of it. And as a rule—much to the hero’s initial chagrin, and eventual (begrudging) acceptance—she wins. And yet…she wins without making him look like a fool or a weakling.

She’s also quite classy, as a rule—classically feminine, caring about her beauty, minding her dresses and jewelry—without being prissy or spoiled in any way. You’re as likely to see her slouching against a bar as sitting up straight at a card table. She’s comfortable and secure in her beauty and charm…and lets the hero know it with a mischievous glint in her eye. The go-to pose for the Hawksian woman involves hands on her hips, as she coyly proclaims: “I’m hard to get. You have to ask me.”

The Hawksian Woman is, truly, the hero’s equal—while at the same time being different. Hawks held the “power couple” as the ideal, and it shows. (Not surprisingly, The Grey Fox was married to such a cool gal, famously nicknamed “Slim”.) The romance is grounded in mutual respect, and friendship along with attraction. Their strengths and vulnerabilities are different—and that’s what makes them perfect for each other.

She’s not “one of the guys”. She is, however, one of the gang…and brings her own skills, as a woman, to help save the day in her own way.

Such is Feathers, the professional gambler played magnificently by Angie Dickenson in one of her first onscreen roles. She doesn’t take in part in the gunfights—at least not directly. But she’s there when Sheriff Chance needs her most, giving him the emotional support he’d never realized he needed until now…and she goes on to give him pointers and call him out on his stubbornness when need be.

For good measure, as Tarantino famously put it: “If I ever think I might go steady with a girl…I show her Rio Bravo, and she better like it.”

FOR BONUS POINTS:

Rio Bravo thankfully does away with the typical trope of the sheriff/marshal banning guns in the town. Early on, Sheriff Chance makes it a point to allow The Colorado Kid to keep his guns, when the latter makes clear his willingness to comply with the law. No gun control, here—the implication is, Wayne and Hawks got that it’d just be counter-productive…even in the Old West.

As Ben Shapiro put it, “You can’t beat Westerns for Conservatism.”

Unless it’s High Noon, of course.

WHY IT’S A GREAT FILM:

Phew, thought I’d never get here, did you? In my defense, this film just oozes Conservatism, and intentionally so. But with all that out of the way…

Quentin Tarantino has called this one of the great “hangout” movies. That is, the biggest part of Rio Bravo’s charm is in the characters—as opposed to anything else. The storyline is very basic—the town’s under siege by bad guys, who are waiting for the heroes to try something…and vice versa. In the meantime, said heroes relieve the tension on their end through their interactions with one another. The plot is almost incidental—sometimes a plot turn happens, upping the stakes…as if just to remind us the film is going somewhere. But that’s just icing on the cake.

The real flavor is in “hanging out” with Sheriff Chance, The Dude (Dean Martin—yes, good ol’ Dean-o), The Colorado Kid (Ricky Nelson—the singer, essentially the Justin Timberlake of his day), Stumpy (Walter “Old Codger Voice” Brennan), Carlos & Consuela, and Feathers. They all have their complexities, and wants and needs—and many of them have arcs, and compelling ones at that. Chance has to learn to open up, and accept help when it’s offered to him. Dude’s a recovering alcoholic, and has to regain his confidence in himself. Colorado enters as a bit of an “it ain’t my business” libertarian…and has to learn there are times to stick one’s neck out and intervene. And Feathers has a past she’s trying hard to live down, without sacrificing her love of The Game.

Rio Bravo’s appeal, politics or no, comes from “hanging out” with these characters, all so well-crafted that they could almost be our friends. And when we get to that magical moment, where the guys have all come together at last, as a power team…well, the moment of fellowship is a joy to behold, and they all sit back and enjoy hanging out together, “as men”:

Redemption…pulling yourself out of despair, to win the day…and individuals, men and women , coming together to triumph over evil. Can’t get any better than that.

BY THE WAY…

A couple of trivia notes: Listen carefully to the mariachi rendition of “Deguello”, featured as a major plot point. Fans of the Clint Eastwood Dollars Trilogy should find it eerily familiar. That’s because, when Sergio Leone first brought on Ennio Morricone to score A Fistful Of Dollars, he told him to look at Dimitri Tiomkin’s Rio Bravo score for inspiration.

Also, turns out Rio Bravo is the actual source of one of the most famous movie lines in history. During the climax, Stumpy calls out: “How do you like them apples?” Seems Will Hunting loves the movie, too.

One more thing, just to be clear: The “hangout” element to this film means it’s in no real hurry to move along. (It’s 2 hours and 20 minutes.) As such, if taut, lean, “thrilling” films are more your cup of tea, and you don’t care for slow-paced “meditative” stuff…this might not be for you. But Hawks and Wayne made sure to account for that—half-remaking the film in 1966, as El Dorado.

While the basic themes of Rio Bravo are still present, El Dorado is much more plot-heavy, based as it is on a novel (The Stars In Their Courses, if you’re interested). It’s faster-paced, the comedy is “bigger”, and there are two girls in this one. Also, see James Caan in his younger, pre-Godfather days…Robert Mitchum as John Wayne’s equal (though he himself gets drunk, like Dean-o)…and Ed Asner as the bad guy. Oh, and the theme song is pretty awesome, too—try not to sing along with the chorus by the song’s end.

WHAT’S NOT ON THE LIST:

High Noon (1952)—for the reasons listed above. I should add, though, that I’m very aware that the historical context of the film is long past…and in the absence of such, High Noon has enjoyed a new image, as a monument to the heroic individual who will stand firm against evil, even when no one else will. Alas, context or no, High Noon still undercuts this theme by 1) making clear that the town isn’t worth it, and 2) having Marshal Kane throw his badge away and leave, in the end.

In other words: So…what was the point? Why did he stay and fight? If he’s “standing up for what he believes in”…okay, then what does he believe in? Was Kane just trying to prove something to himself…even if it meant driving his wife away (with no anticipation that she’d change her mind at the last second)? As Price notes, “[Gary] Cooper is the great hero brought low by marriage. He has become cowardly, timid, and conflicted. He only fights because he is too afraid to run away. The message of Cooper’s marshal is that there is no place anymore for individual heroism.”

Again, my strongest apologies to Bill Whittle. But there are other cinematic monuments to individuality and the lone hero—which don’t undercut that heroism.

Buy the Rio Bravo movie on Amazon, here. And stay film-friendly, my friends.

Comments

Leave a Reply