“Late summer, autumn, 1968: Kurtz’s patrols in the highlands coming under frequent ambush. The camp started falling apart. November: Kurtz orders the assassination of three Vietnamese men and one woman. Two of the men were colonels in the South Vietnamese army. Enemy activity in his old sector dropped off to nothing. Guess he must have hit the right four people. …If he’d pulled over, it all would’ve been forgotten. But he kept going. And he kept winning it his way. And they called me in.”

When I first started this series, I made sure to credit my direct inspiration for it, John Nolte’s “Top 25 Left-Wing Films”. It’s a masterful, compelling series and I highly recommend Conservative movie-lovers give it a look. But I also made sure to note that I pretty firmly disagree with his assessment of Apocalypse Now as a Left-Wing film.

Really, the fact that John Millius—Hollywood legend, notorious maverick, master of epic action (see Conan The Barbarian), and noted Conservative (Red Dawn, anyone?)—wrote the screenplay came as no surprise to me. ForApocalypse Now, as so many of my favorite Conservative films and TV shows do, masterfully pulls the “bait-and-switch”.

…Maybe a bit too masterfully, if Nolte’s piece is any indication.

Look, all film is subjective, as a great online critic has often said. Nonetheless, I was very surprised to see Francis Ford Coppola’s greatest non-Godfather film on a “Left-Wing Film” list. I remember when I saw this masterpiece for the first time, and getting the exact opposite impression.

Bear with me. And by the way—anything in the 2001 Redux version not in the 1979 theatrical cut, I’ll be sure to note as such.

Editor’s Note: In April of 2017 writer Eric M. Blake began a series at Western Free Press naming the “Greatest Conservative Films.” The introduction explaining the rules and indexing all films included in the series can be found here. Liberty Island will feature cross-posts of select essays from the series with the aim of encouraging discussion at this cross-roads of cinematic art with political ideology. (Click here to see the original essay. Check out the previously cross-posted entries on Jackie Brown, Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Unforgiven, and Hail, Caesar!) If you would like join this dialogue please contact us at submissions [@] libertyislandmag.com.

WHY IT’S A CONSERVATIVE FILM:

Oftentimes, it’s the little things that count—the details, the little things that, when you notice them, suddenly put all the big, blatant, in-your-face stuff in a new context…a new “spin”.

So, let’s look at the big things for a moment. As Nolte puts it:

[C]o-writer/director Francis Ford Coppola…portrays America’s involvement there [in Vietnam], and our military men in particular, in the harshest and most disturbing ways imaginable. At best, we are forever indifferent to everything and everyone, most especially human suffering. At worst we are murderers of women and children and our government is involved in the kind of secret Black Ops the Left was sure WikiLeaks would finally reveal when just the opposite turned out to be true.

We also epitomize the term Ugly American, treating our South Vietnamese allies like children or as though they don’t exist, and there is no amount of brutality we won’t rain down on our enemies in the North. We are borderline terrorists willing to lay down intense air strikes on villages where children can scramble for cover just so we can surf. [And] we use the dead in ways to strike fear in the hearts of the enemy and casually toss around racial slurs to describe anyone who doesn’t look like us.

So…is all that true, about Apocalypse Now?

Sure looks that way.

And yet…

THE “BAIT-AND-SWITCH” METHOD:

See, here’s the thing: Those of us tragically—and understandably—conditioned to be suspicious of propaganda in Hollywood will oftentimes suffer an unfortunate side effect. Namely, we’ll see the Left-looking “bait” of a film, and not allow for the possibility that it might well be bait.

(Example: The Lone Ranger—a film I freely admit to enjoying, even though it’s apparently fashionable to hate on it. There, the bait is “White Man’s Guilt” a la Dances With Wolves or Avatar. The switch? As a sequence involving a Cavalry officer and a Mexican Standoff makes clear, the “guilt” comes about by individual choice, not racial inheritance. Further, from the beginning, John Reid’s initial Guns-Are-Not-The-Answer mindset is mocked—and only when he accepts the need for them can he become The Lone Ranger. But I digress.)

It’s especially unfortunate…because this method is arguably the most effective weapon in our arsenal. Imagine, for example, a film with the set-up of “noble journalists fighting to expose an evil corporate executive”…but with the payoff of: the mysterious source giving the journalists the information they needed was another corporate executive, perhaps in the same company—and now that the bad guy’s taken down, the good businessman can successfully clean house and bring the company back. For bonus points, the good guy was the “cold” fellow the journalists were sure “doesn’t care about anything but company profits” or something….

Imagine the effect on the Lefties in the audience—those at first following along with grins at their mindset being validated…only to have the rug pulled out, jolting them into reality. And they can’t call it “contrived”, because the plot just works.

That’s the thing about our message. It’s grounded in logic. You don’t have to “contrive” things for it to work.

SO…what “switches” are in this one?

THE “SWITCH” OF KURTZ’S REBELLION:

The mission’s kicked off when Willard’s superiors tell him that Kurtz was once an outstanding, immensely respected officer—but for no apparent reason, “his ideas and methods became…unsound.” Now, he’s formed an army of natives that “follow every order, however ridiculous.” “He’s operating without any decent restraint—totally beyond the pale of any acceptable human conduct.”

All vague, generic…unclear. What specific “crime” is he guilty of? Well…

“Kurtz had ordered the execution of some Vietnamese intelligence agents—men he believed were, uh—double agents. So he took matters into his own hands.”

What’s the explanation of all this?

“Well, you see, Willard, in this war, things get—confused out there. Power, ideals, the old morality, and practical military necessity. But out there with these natives, it must be a temptation to—be God. …Sometimes, the dark side overcomes what Lincoln called ‘the better angels of our nature.’ Every man has got a breaking point. You and I have them. Walt Kurtz has reached his—and very obviously, he has gone insane.”

Willard agrees…but as time goes on, he realizes more and more that the higher-ups didn’t tell him the whole story. Particularly that—as the page quote makes clear—Kurtz’s “murder” of the intelligence officers was right. They weredouble agents. Kurtz was simply willing to do what had to be done, though his superiors clearly weren’t.

And as Willard reads Kurtz’s critiques of how the war’s being conducted, he—and we—can’t help seeing how on-point the man was, as the film’s events vindicate his words.

“No wonder Kurtz put a weed up Command’s a—. The war was being run by a bunch of four-star clowns who were gonna end up giving the whole circus away.”

“YOU HAVE NO RIGHT TO JUDGE ME”:

When Willard finally meets Kurtz, it’s left for us to decide—along with him—whether he’s now crossed the line, or not. Willard himself notes that, regardless of anything, those audio recordings were pretty nuts. But if Kurtz isinsane…it’s not the “war climate” that made him so (as Command—and the Left—would have it).

It’s because the brass refused to fight the Vietnam War to win—because LBJ and the Democrats ran it with terribly shackling rules of engagement that kept our boys from doing what needed to be done. As such—as Kurtz himselfmakes clear in that famous “Horror” speech to Willard—the enemy had a major upper hand. They weren’t tied down or shackled by “judgment”—they had the will to get their hands dirty.

And as he notes in the essays and letters Willard reads in the boat…the higher-ups just didn’t take the war seriouslyenough—and Willard agrees.

“In a war, there are many moments for compassion and tender action. There are many moments for ruthless action. What is often called ‘ruthless’—but may in many circumstances be only clarity: seeing clearly what there is to be done and doing it, directly, quickly, awake. Looking at it.”

Kurtz “went insane” because he never had the support he needed to fight the war well. With all the red tape and “rules” tying his hands, he had to go rogue and form his own army…and it may or may not have tragically gotten to him. Certainly, it’s broken him—and Willard ultimately concludes that Kurtz wants to be assassinated.

That’s just the way it has to be.

KURTZ REDUX:

Price’s Conservative Guide To Films asserts that Apocalypse Now, theatrical cut, actually is a Leftist film, whereas the Redux is Conservative—contending that the extra scenes help add more “switch” to the bait. While I disagree with the first part, the Redux does indeed have more material for Conservative “spin”. Here, we have Willard reading an essay by Kurtz underlining how the colonel understood all too well that Command wasn’t taking the war seriously enough—particularly considering how the soldiers have one-year tours of duty where they enjoyed “cold beer, hot food, and rock-n-roll” as “the norm”. In short, Kurtz argues, the war’s being made comfortable—and the short length of tours hampers combat experience, and therefore professionalism.

In the final act, the Redux has Kurtz reading to Willard a sample of excerpts from Time and other magazines depicting the constant “new feelings” of optimism about the war—his point being how the U.S. government kept wanting to have it both ways—wanting to win the war, without getting through to their heads that it takes a hard, conscious effort to, well, win a war.

THE “SWITCH” OF COL. KILGORE AND THE “SURF” ATTACK:

He loves the smell of napalm in the morning. He’s a bit too gung-ho and eager to blow stuff up. He has his air cavalry blast Wagner’s Flight Of The Valkyries in what may or may not be a reference to the Klan ride in Griffith’s notorious Birth Of A Nation. And he wants the beach boys in his regiment to go out and surf, while the battle’s still going on.

The man is nuts. And Willard can only observe in bitter amusement:

“If that’s how Kilgore fought the war, I began to wonder what they really had against Kurtz.”

Still, it’s not that simple. Let’s take a look at the little things.

First, Col. Kilgore’s intro has him grant a dying “Charlie” his request for water, because the man wins his respect by holding on to the bitter end—to the point of holding in his own guts with a pan. Kilgore’s a warrior who gives a nod to any man with, well, “guts”—even if he’s the enemy.

Now for the air cavalry raid—Wagner and everything. At first, it really does seem like the Kerry/Obama smear of “air raiding villages and murdering civilians.”

And yet, that soon changes. The “village” fights with the kind of weaponry expected in combat—shooting bombs into the bay where Kilgore’s ordered the surfing.

There’s even woman throwing grenades at a medevac helicopter.

Actually, dialogue in a previous scene already established it’s a heavy “Charlie” instillation. The civilians are just being used as human shields at best…disguises (the bomber) at worst. It’s not emphasized as much as I’d like, but it’s there.

In the end, we can’t merely frown at Kilgore as a Brutal Warmonger. Insane as his methods may look…it’s just not that simple. War rarely is.

KILGORE REDUX:

The Redux version provides a few more moments for Kilgore that frankly underline the “switch” part of all this—making it much more blatant. Here, in the middle of the battle, a real civilian woman runs up to the Americans with her child, clearly wanting them to keep the kid safe from the carnage. Kilgore makes it a point to grant her request—saving the mother, too.

It isn’t just that he saves them—it’s the fact that the mother makes the request in the first place. There, we see a shot fired against the whole “We were monsters over there, and they hated us” narrative. The woman sees the Americans as men with hearts—who want to do the right thing, war or no war. And her assumptions are vindicated.

Good enough for me.

IN THE END…

If Apocalypse Now has a “message” about Vietnam—and about war in general, actually—it’s this:

War is dark, in and of itself. No amount of moralistic whitewashing can change that. Thus, if we’re going to fight a war, for whatever reason…we’d better be willing to go all the way and do whatever is necessary for victory. If we aren’t willing, then we’re hypocrites—and that hypocrisy only results, at best, in a war that goes on for far longer than it has to. At worst, it results in humiliating defeat.

FOR BONUS POINTS:

The “sampan search” sequence seems very much like an “obligatory war atrocity” scene so common in Vietnam/Iraq-War films. However, keeping in mind all of Kurtz’s critiques about the handling of the war, it serves to underline his theory that many of the boys serving one-year tours weren’t being properly “prepared”. Certainly the crew of Willard’s boat is so used to chilling around that they don’t seem particularly cut out for tense situations. And alas, it leads to tragedy.

Besides…Willard told them to forget the search, and they didn’t.

Finally, it’s not a small thing that Kurtz’s compound is in Cambodia. The North has supply lines running through Laos and Cambodia during the war. Alas, LBJ’s “limited war” nonsense led to forbidding our side from doing anything about it, because those countries were “neutral”, you see. In other words, for those in the know, it’s more proof that Kurtz had been, in so many ways, in the right.

WHY IT’S A GREAT FILM:

Where to start? By all accounts, it’s one of the greatest war movies ever made—powerful, haunting, poetic. It’s the sort of film that sticks with you forever, one way or another. I emphasize “haunting”: There’s a specific, special mood to Apocalypse Now that, to the best of my knowledge, no other war film has ever truly duplicated. It’s the mood of a deep sleep—a dream. A “realistic” dream…but a dream, nonetheless. Surreal, not in the blatant David Lynch sense—but in the sense of how you feel, when you watch it.

Can we call it “dark”? Well…I honestly couldn’t tell you. All I know is, that song of The Doors, “The End”, was the perfect choice of Coppola’s to begin the film. The gradual, mellow, gripping…weird melodies of that song reflects the gradual, mellow, gripping…weird melodies of the film itself—plot, character, soundtrack, cinematography, mise-en-scene*, theme…everything. And the images accompanying that song blend perfectly well with it—to the point where it’s one of my all-time favorite openings of a film, ever.

For those not in the know, Apocalypse Now is based upon Joseph Conrad’s novel, Heart Of Darkness—set on the Congo in the days of the British Empire. John Millius noted that he’d written the screenplay essentially on a dare—a professor of his had firmly stated that the book was un-adaptable for the screen….

Well, Millius took that as a challenge. And the result was a masterpiece.

MARTIN SHEEN AS CAPT. WILLARD:

The excellent website TV Tropes posits a theory that Apocalypse Now, despite the Vietnam trappings, is actually a Film Noir. Maybe that’s part of what draws me to it. At any rate, Willard certainly brings that “disenchanted outsider” vibe, complete with the occasional wry wisecrack about the situation—Chandler-esque lines like, “Charging a man with murder in this place was like handing out speeding tickets in the Indy 500.” Willard’s an outsider, and he knows it—and though it haunts him that he doesn’t really have a place in the world around him…he seems to accept it.

And the “case” for this detective is to figure out 1) why Kurtz went rogue, and 2) whether he’s truly “insane” enough to validate putting him down.

To boot, Willard’s a hard drinker and smoker. At least until he’s on the case.

Anyway…before Martin Sheen was Jed Bartlett—and long before he let that go to his head enough to presume to lecture the Electoral College—he was Capt. Willard. And he plays the part beautifully—with no pretentions here, no false ego.

ROBERT DUVALL AS COL. KILGORE:

The movie may be about Willard and Kurtz. And technically, Kilgore may be a minor character, only on for a few scenes. But when Robert Duvall is on screen, he commands it—and Col. Kilgore has become one of the most iconic characters in cinema history.

“Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. Y’know, one time we had a hill bombed for twelve hours—and when it was all over, I walked up. We didn’t find one of them—not one stinking (bleep) body. But the smell—y’know, that gasoline smell—the whole hill…! It smelled like…victory…. Someday, this war’s gonna end.”

He’s got a presence, and he uses it. And there’s a nice element of comedy about him too—with his boyish enthusiasm for surfing.

DENNIS HOPPER AS THE PHOTOGRAPHER:

He’s a bizarre sort of Greek Chorus when Willard and the surviving members of the crew arrive at Kurtz’s stronghold. He may or may not have been the guy who sent the last photo of Kurtz that Willard received. Hey may or may not even have any film in that camera of his, as he snaps it around. All we know is, he loves to talk—and talk—and talk, offering his passionate evangelism about how Kurtz has opened his mind. Nolte calls it “a poetry of black cynicism”—and notes that it’s as good an explanation for what’s going on with Kurtz as any.

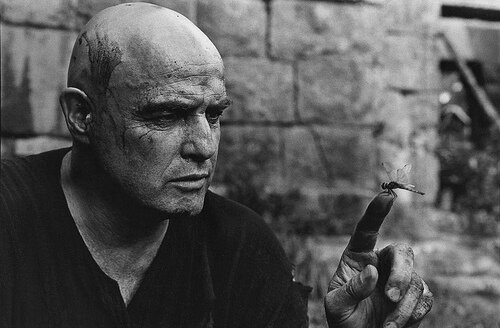

MARLON BRANDO AS COL. WALTER E. KURTZ:

Supposedly, Marlon Brando himself helped Coppola figure out the final ending of the movie. When he showed up Don-Corleone-fat—apparently no one told him he needed to lose weight for the role—Coppola knew darn well he couldn’t use the script’s action-packed finale (more on that later). But he had to come up with something that would satisfy all the build-up…and would fit a heavyset Kurtz that’s more of an emperor-priest than a soldier, now.

So, he told Brando to read the “Kurtz” section of the book…and the two of them effectively improvised a more philosophical, psychological payoff. And while a lot of people seem to think this last act is the weakest of the film…well, I don’t see how, myself. A weird-feeling film like Apocalypse Now deserves a weird-feeling ending. And that’s what we get.

Brando’s Kurtz is constantly enshrouded in shadow, in mystery. And in his conversations with Willard, he continues to challenge Willard’s assumptions about him…about the mission…and about exactly what he should or shouldn’t consider “insane”.

“Are my methods unsound…?”

“…I don’t see…any ‘method’…at all, sir.”

“…I expected someone like you. What did you expect?”

Brando is often hailed as one of the greatest actors of all time. Often, to be blunt, he fails to live up to that. But often, he succeeds—and this is one of the latter. Kurtz is at the end of his rope…and he knows it. Quiet, somber…resigned to his fate, yet still challenging Willard to answer the questions he must ask himself. He wants Willard to kill him—but only after Willard acknowledges why he will kill him…after he acknowledges to himself the truth behind all the events that have led to this.

CLEAN’S CASSETTE:

Laurence Fishburne—aka Morpheus and Perry White—has one of his first big roles in this film, as “Clean”, the youngest member of the boat crew transporting Willard. After the point of no return, he is the first of the team to die.

He dies in a sudden firefight against an unseen enemy hidden in the jungle shores…while a cassette tape he’d gotten in the mail plays on the boat’s speakers. It was a cassette from his mother, talking about how things are going back home. And as the other guys gather around his dead body, the battle over…“Clean’s” mother notes how eager she and the family are to see him come back home….

Trust me, it doesn’t feel heavy-handed. It’s hauntingly tragic—and one of the most powerful moments in the film.

ABOUT THE REDUX:

In 2001, Coppola released his extended director’s cut—the Redux. He rearranged a few scenes (putting the sequence with the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction” a bit later in the film, for one)…and more importantly, added a bit more. We’ve already talked a bit about some of the additions. Here are the remaining big ones:

The most prominent changes begin with Col. Kilgore. He has more of an actual introduction, here. There’s the mother and child, of course. But most significantly, there’s a short comical subplot where Willard, fed up by the man’s antics about surfing amid a battle, swipes Kilgore’s surfboard as if to wound his ego.

That night, it pays off—some Hueys fly where Willard and company are resting, and Kilgore goes on speakers to demand the board back. But not seeing them, that’s all he does, and Willard shares a chuckle with the guys—a rare moment of chemistry and camaraderie with them. It’s a cute series of sequences, and a nice addition if you didn’t care for the lack of warmth among Willard and the crew in the original cut.

Later on, there’s a sequence at a fallen-apart MASH facility—all but abandoned. By chance, the Playboy girls from earlier in the film had to land there, and Willard negotiates for some R-and-R for the crew. Hilarity ensues. Or at least it tries to.

I tend to cringe a little bit when a fellow Conservative calls something in a film “unnecessary”. Still, even speaking from an artistic standpoint, this sequence kind of is. It’s a very weird deviation—apparently meant as a “breather”, as if the film wasn’t already long enough. As it is, it breaks the tension without actual justification. It isn’t even that “sexy”—it’s more played for awkward comedy than anything else.

REDUX: THE PLANTATION:

The biggest addition to the Redux comes after “Clean’s” death. Willard and the crew stumble upon an isolated French colony. The inhabitants give “Clean” a soldier’s burial, and the others are treated to dinner and rest for the night.

At dinner, Willard and the plantation leaders have a most…interesting conversation about the colony, and it leads to an intricate political discussion, with the Frenchmen disagreeing over the morality of the war. Finally, however, the leader notes that the French’s failures in Indochina came out of Paris appeasing the “peace” protestors—and “traitors—Communist traitors at home!” A young man follows up, imploring Willard that America could win if it wanted to—if it would only learn from France’s mistakes.

I didn’t include this in the “Conservative” section only because of all the different arguments at the table, here—there’s even a Frenchman defending the Socialists, arguing with the leader that they aren’t Communists…. Basically, nothing is settled…except that the French can only look on in sadness at America in such an eerily familiar situation.

After this, Willard finds himself spending the night with Madame Sarrault, a young widow who’s taken a liking to him. She notes how drained and lost he is. There is a strong notion that she’s touched something in him…and she even tells him that “Your home is here.”

I actually like this sequence, very much. More than any other addition, this is what makes the Redux almost a different movie, for the simple reason that it puts a new spin on the ending. In the theatrical cut, after killing Kurtz, Willard faces an uncertain future. Here…the implication is that he just might settle down with Madame Sarrault…at long last, finding peace.

“There are two of you—don’t you see? One that kills. And one that loves….”

ABOUT THE DELETED SCENES:

Usually, I don’t give these a section of their own—but it’s part of my critique of the Redux. Were I the one assembling it, I might’ve replaced the “Bunnies at the medevac” sequence with some of the deleted scenes involving Kurtz’s compound.

One of my favorites involves Kurtz talking to Willard while the latter’s in the bamboo cage. Kurtz calls out Willard for being afraid to “look”…and then, he specifically calls out Washington:

“They want to win this war. But they can’t bear to be thought of as ‘cruel’. They want to destroy the enemy. But they hate to admit that they’re simply ‘murdering’ them. And they insist that they are ‘civilized’—they insist that they are ‘moral’—they insist that they are ‘ethical’. And you will find, later or sooner, Captain—that those words are meaningless in this wilderness. Meaningless.”

Willard, however, rejects the idea that morality should be just discarded in warfare. Perhaps the scene was cut because Coppola felt it “clears up” the ambiguity a bit too much—more openly setting Willard and Kurtz at odds.

The other has Willard actually talking with his predecessor, Colby—the last guy Command had sent to assassinate Kurtz, only to join him. Colby explains that the NVA attacked, and he found he had to help Kurtz against the realenemy. It’s a very interesting moment—and it actually helps with the ambiguity, as it builds on how Willard had found himself agreeing with Kurtz’s insights about the war.

Oddly enough, the story seems to refer to what may or may not have been John Millius’s original ending. Perhaps Coppola wrote in the moment, as a reference…?

HOW IT ALL ENDS:

There’ve been conflicting stories as to exactly how the film was originally supposed to end. Some sources say Willard was supposed to join up with Kurtz, as they fend off an attack—only to have Kurtz die in battle. Others say it was supposed to be an action-packed final duel between the two of them.

Whatever it was, Millius has insisted that he’d always intended for Kurtz to die in the end, with that immortal final line of his, “The horror…the horror….” Just like in Conrad’s original book.

Ultimately, Coppola found the perfect end to this mad film—a ritualized killing, conveying how Kurtz has, as Willard himself notes, submitted himself to the laws of the jungle. It’s all over…but Willard knows full well the world isn’t exactly the better for it.

By the way…what are we to make of the scribbled down message Willard finds on a thesis he finds on Kurtz’s desk? “DROP THE BOMB—EXTERMINATE THEM ALL!” Is he calling for annihilation of the North? Is it a message to Willard to go ahead with the air strike and finish off his troops? Or is it just…a final expression of rage—Kurtz having crossed the line into insanity?

Who knows? Just like we don’t know for sure what Willard plans to do as he takes the boat out onto the river….

NOLTE’S THEORY:

John Nolte’s article has a most fascinating interpretation of the film—that it’s essentially Willard going through Purgatory; that right after the introduction’s fade to black, Willard killed himself, and his “mission” to kill Kurtz—his symbolic dark self—is his payment for all his sins as a covert op.

I actually get a kick out of considering this reading. It certainly goes a long way towards explaining the constant mood of “weirdness” throughout the film, which could almost be described as darkly…dreamy.

Incidentally, it’s also why Nolte doesn’t care for the Redux: The added scenes kinda break from the “dream state” motif, to him. I would argue it doesn’t have to—Madame Sarrault could be seen as an angel encouraging him that there is a reward at the end of all this….

Anyway, my interpretation isn’t quite as elaborate—but like Nolte’s, it sort of relies on what version you watch.

MY THEORY:

Basically, I’ve long entertained the idea that most of the introduction sequence takes place after the events of Willard’s mission. I say “most”, because I count Willard snapping and punching the mirror as the beginning of the “flashback”—basically because his hand’s cut up when the guys arrive at the door to recruit him.

At any rate, pay close attention to Willard’s narration. During the intro, we hear him talking in the present tense (“I’m still in Saigon,” “I get weaker,” etc.). As we fade into his beginning his martial arts practice (leading to the mirror punch), the narration turns to past tense—and stays that way for the rest of the film.

More importantly, there’s the footage that fades in and out, amid Jim Morrison rolling out “The End”—the napalm strike…and especially the image of the stone face, fading into sight shortly after Willard’s own.

It’s the stone face that guards the entrance to Kurtz’s fortress.

Like I said, though, the Redux might throw a wrench into that—if you interpret the plantation sequence as an opportunity for Willard to settle down, when he’s through.

But then…maybe he just isn’t “through”, quite yet. Maybe, before he can retire with his mademoiselle, he has to emotionally recover in Saigon, while he waits for the debriefing to conclude….

Well, it’s fun to speculate, either way.

BY THE WAY…

Originally, George Lucas wanted to direct this—low-budget, with a couple of helicopters.

Way, way back, Orson Wells wanted to make a Heart Of Darkness film. It would’ve been interesting. Imagine if he’d cast a young Marlon Brando as Willard (techincally, “Marlow” in the book), with Wells himself playing Kurtz.

Yes, that is Harrison Ford as the nerdy guy giving Willard the briefing about Kurtz in the beginning. Apparently the moment where he drops the dossier, the contents spilling out, wasn’t scripted. He actually dropped it by accident.

The photos of Kurtz come from previous war films starring Brando—which is why he’s fit, in them.

The TV news guy calling out “Don’t look at the camera!” is Coppola’s director cameo.

The poem Kurtz reads, while the photographer rants, is T.S. Elliot’s “The Hollow Men”…to which Elliot attached a quote from Heart Of Darkness. A quote mentioning Kurtz.

And the moment where Kurtz throws the book at the photographer—calling out “MUTT!”—wasn’t scripted. Brando was legitimately frustrated at Hopper’s ranting.

Speaking of unscripted, that famous “Horrors” speech of Kurtz’s was completely, 100% ad-libbed by Brando.

For those of you interested in the making of this film, Coppola’s wife made a very famous documentary following along the process: Hearts Of Darkness. It’s notorious for showing just how stressful the whole experience was for poor Coppola. There were a lot of roadblocks and hardships, to put it mildly. Filmmaking is not for the faint-hearted.

*(For the non-cinephiles among you, that’s a film term from the French that literally means “look and feel”. It refers to the movie’s scenery, color palate, sound effects, and general atmosphere—all rolled into one concept.)

Buy the movie here. And stay film-friendly, my friends.

Any recommendations for films to make this series? Read the rules, here, and let us know!

***

Eric M. Blake Bio:

Eric M. Blake is a recent graduate of the University of South Florida, with a Bachelor’s in Political Science and a Master’s in Film Studies. As that implies, he is very passionate about political theory and filmmaking–and the connections between the two. Inspired by Andrew Breitbart’s axiom that “Politics is downstream from culture”, he is deeply fascinated by the great influence that popular culture has on public opinion, and is a firm believer in the power of storytelling. He proudly owns his second copy of Ben Shapiro’s Primetime Propaganda… his first copy having been worn out though intense re-reading.

Eric was raised by Conservative Christian parents, but first became especially passionate about politics in high school, through reading up on economic theory. He also first read The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged around this time, for the ARI’s essay contests. He now owns a great deal of Ayn Rand’s work. Also included in his library are the collected works of Rush Limbaugh, Mark Levin, Ann Coulter, etc.

Eric is no stranger to writing commentary, as the writer of the Conservative Considerations column on CampCampaign.com, and as a film critic and commentator on FlickRev.com. He has also carried on the Conservative tradition of talk radio commentary, as the host of “Avengers of America” for the USF student radio station, Bulls Radio. In the meantime, he is practicing what he preaches: Striving to enter the professional realm of Hollywood, he has already written and directed short films for the Campus MovieFest, which can be found on his YouTube channel, Hard Boiled Entertainment.

****

Photo by Todd Barnard

Comments

Leave a Reply