“We all have it comin’, kid.”

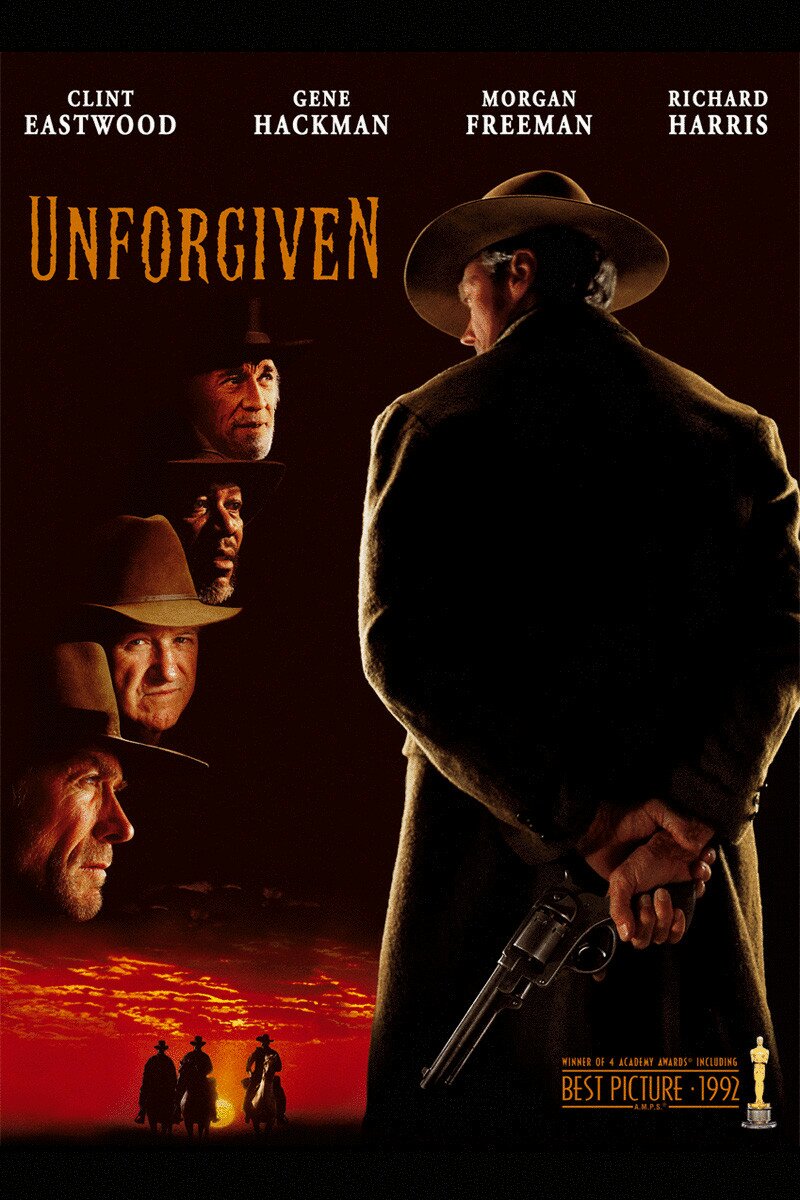

Back to Clint Eastwood, folks! And there’ll be more from him to come. Here, it’s a legendary gem he not only starred in, but directed—the grand deconstruction of the Western genre itself: Unforgiven.

Some call it “the greatest Western of all time”. I wouldn’t go that far. Frankly, I’d say the mindset behind that’s precisely what led to the glum, dreary, dirty, moody sort of style that far too often seems inevitable to the “oaters” of today. You’re far more likely to see that than a beautiful, sweeping, Romantic epic like in the old days. Even when today’s Westerns do try to be “fun” again, the color palate’s either bleached out (The Lone Ranger) or “browned”-out (the 2016 remake of The Magnificent Seven).

Only Quentin Tarantino and Seth MacFarlane seem willing to buck that trend—and in the latter case, well…A Million Ways To Die In The West was what it was. Stylistically, it was everything we’ve been missing—beautiful color palate, Berstein-esque music, and even Monument Valley for good measure. Substance-wise…well, Seth and Charlize Theron can only rant about the harshness of the West so many times before I finally tear my hair out and scream “I GET IT, ALREADY!!!”

Editor’s Note: In April of 2017 writer Eric M. Blake began a series at Western Free Press naming the “Greatest Conservative Films.” The introduction explaining the rules and indexing all films included in the series can be found here. Liberty Island will feature cross-posts of select essays from the series with the aim of encouraging discussion at this cross-roads of cinematic art with political ideology. (Click here to see the original essay. Check out the previously cross-posted entries on Jackie Brown, Captain America: The First Avenger, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and Captain America: Civil War.) If you would like join this dialogue please contact us at submissions [@] libertyislandmag.com.

More deconstruction, even there. So in the end, there’s only Quentin—for now, at least. (Even with him, that’s only Django Unchained; The Hateful Eight more-or-less fits the “Unforgiven-esque” trend, just with a Tarantino “spin”. But I digress.)

But I don’t blame Clint for all that. I don’t even blame Unforgiven for that—the 1990s went on to give us a lot of greats that did emulate the Classical Western of John Wayne and Co. It’s just that a lot of filmmakers afterwardseem to have looked at Unforgiven, and learned the wrong lessons—the notion that a Western must be deconstructive and angsty and darkly lit, in order to be “taken seriously”.

I’m reminded of Frank Miller, and his masterpiece The Dark Knight Returns (which you might remember my talking about in my Batman v Superman article). After that seminal Batman storyline (along with Alan Moore’s Watchmen), comic books en masse started going “dark-&-edgy”—and we saw the rise of “Nineties Anti-Heroes”…including Spiderman’s arch-nemesis Venom turning out to be somewhat (anti-)heroic himself, in his own Punisher-esque way. Certainly not quite so bad as, say, Carnage.

Well, kicking off that “Dark Age” of comics was decidedly not Miller’s intent—and he’s since contended that his crazy/zany/“fun” sequel, The Dark Knight Strikes Again, was him making a firm point about that.

I’m not saying I expect Clint to do a “reconstructive” Western—he’s said himself, he’d be all right with Unforgivenbeing the last Western he ever made. Would be nice, though.

All right, enough of that. On to the movie. Some SPOILERS ahead, of course…but the plot points are arguably a bit inevitable. Anyway…

WHY IT’S A CONSERVATIVE FILM:

Unforgiven was another film that wasn’t exactly on my radar of “films to write about”, for this series. I miss a lot of things, even about movies—which is why I encourage readers to suggest some films of their own for me to check out.

In this case, I’ve been looking around for Conservative websites that talk about pop culture, and I believe it was Andrew Klavan himself who directed his podcast fans to Smash Cut Culture. So I looked around that site, quiteimpressed at what I saw (and yes, I recommend it, myself). And wouldn’t you know it…there’s an article about Unforgiven, going into the Conservatism in the film.

The author of that article, Cody Morgan, expanded on those ideas in a piece for the Foundation for Economic Education. As was the case for The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Returns, I don’t have much to add to his points…so I’ll let him pretty much take the reins here.

Pun not intended—at least, not until I wrote it.

Anyway, Unforgiven’s an example of something I mentioned in my Introduction to this series: A film isn’t necessarily disqualified from the list when the main plot isn’t particularly political. Oftentimes, it’s one of the subplots—maybe a specific character arc. Maybe it’s just a single plot point. Regardless, the Hollywood Left’s given us a lot of examples of propaganda for their side that doesn’t involve the basic storyline, let alone even the premise, of the movie or show in question. Heaven knows how many times we’ve suffered that—going into a film that looked non-political, only to find ourselves treated to a Left-infested plot point, or subplot, or even conversation that frankly added nothing to anything.

Well…fortunately, there are examples for our side, too. In this case…

THE TYRANNY OF LITTLE BILL:

Following a textual prologue about Will Munny’s deceased wife, Unforgiven opens in the town of Big Whiskey, ruled with iron fist by so-called Sheriff “Little” Bill Daggett. And when a cowhand slashes a prostitute’s face for her daring to laugh at him at an awkward moment…Little Bill gets a bit arbitrary in his punishment—changing sentences on a moment’s notice from a severe whipping (which, we later see, he’s particularly good at) to a fine—much to the other girls’ rage. Alas, he’s able to get away with it. As Morgan writes:

Little Bill doesn’t allow guns, criminals (with the possible exception of himself), or vigilantes in his town. Despite his reputation for being tough on criminals, however, Little Bill allowed the two attackers to leave after paying a modest fine to the owner of the brothel (presumably for damaging his “property”).

This apparent injustice is only made possible by the amount of power Little Bill has in the town. In this one character resides the pen of the legislator, the authority of a judge, the discretion of a prosecutor, the weapon of an executioner, and most likely, the immunity of a monarch.

Judge. Jury. Executioner. Dictator. Little Bill’s word is law—and on a moment’s notice, with no thought to due process or checks-&-balances, he can decided what punishment gets doled out to whom. And no one in town has the power to stop him. As Morgan notes, Little Bill enjoys a “legal autonomy”. There’s no mayor or town judge identified in town—at least not prominently enough to be remembered by the audience. If they do exist…we can pretty much infer they’re just figureheads. All the power in Big Whiskey rests in the sheriff’s office—at the hand of Little Bill.

And what fuels this tyranny?

THE GUN CONTROL OF LITTLE BILL:

Ben Shapiro said, “You can’t beat Westerns for Conservatism.” And for the most part, he’s dead-on right. However, there’s a severe cancer in many a classical Western—an element that we’re usually expected to shrug off as par for the course, “necessary” to “tame” a wild town—or just keep the peace in a tense situation:

The trope of the “town ordinance”, imposed by the marshal or sheriff, banning guns within town limits. Gun control.

And to its considerable credit, Unforgiven points out one simple fact the anti-gun proponents on the Left refuse to acknowledge: The government has a legal monopoly on force (the police, the military, etc.)—and when the citizenry’s kept from holding a check on that power…well, that’s a clear-cut recipe for tyranny.

It’s the entire reason the Second Amendment exists. The Left can quibble about the “modern” meaning of “militia” all they want, but it’s all about “the security of a free state”—key word: free. And “the right of the people”—not “National Guard members”, “the people”.

Lo and behold:

On several occasions, characters are forcibly disarmed and are then attacked by the town’s only visible government presence, Sheriff Little Bill.

Particularly, English Bob’s disarmed by Little Bill and company—amid protests that “I will be at the mercy of my enemies.” And sure enough, almost immediately after, he’s at the mercy of Little Bill’s fists—the “sheriff” beating him to the ground, kicking the crap out of Bob until his face is bloodied and his spirit broken. And no one can stop him.

Given the amount of power that Little Bill has acquired as a result of banning firearms, one has to wonder whether that vulnerability and the consequent need for a strong protector is a feature, rather than a bug, of weapons bans.

ANOTHER FACT ABOUT GUN CONTROL:

It’s not called attention to, in the film, quite as much as the above—but it’s there, nonetheless. As Morgan lays out, a case could be made, easily, that the “gun control” policy of Big Whiskey is to be blamed for all the trouble that goes down in the film, from the very beginning—and not just because it enables Little Bill’s dictatorial rule:

The inability of the disarmed population of Big Whiskey to use violence when necessary is deceptively key to the plot. …Had the town been armed, the prostitutes [would] have had much cheaper and faster alternatives to pursue the justice they felt they had been denied. It’s also likely that the attack would never have occurred in the first place. The brothel owner, the citizens of Big Whiskey, and especially the prostitutes themselves all have strong incentives to prevent such attacks. Were it not for the town’s ban on guns, they would have had much more effective means to do so.

In a “gun free zone”, would-be murderers and assailants have nothing to fear. And in the absence of repealing gun control, the only alternative is a police state.

Which is, of course, exactly what Little Bill enjoys.

THE BLACK MARKET AMID LITTLE BILL:

It’s a minor point Morgan already brought up, but it’s worth focusing on for a moment: In societies where the government seizes—“nationalizes”, if you will—a good or service, and renders illegal any private production of that…well, say hello to the black market. The greater the tyranny, the greater the underground—because the greater the need for an underground.

In this case, underground justice—because Little Bill’s dictatorship fails to provide it.

FOR BONUS POINTS:

These two are things I did notice on my own—little Conservative details that, in themselves, wouldn’t necessarily have warranted an entry in the series. Still…

This one’s connected to the “gun control” aspect, but it’s worth bringing up on its own: Right after Munny guns down Little Bill and his goons…he heads to the bar to get a drink…and what do we see but a sign proclaiming the saloon a gun-free zone! It’s a priceless visual gag—a perfect punch line, underlining the self-defeating foolishness of the entire concept.

Also, the whole thing about the fictionalized legends might provide a nice commentary on media bias and “fake news”. After all, many of the “legends” in the West came about by newspaper writers sprucing things up, either for sensationalism (exaggerating Wild Bill Hickok’s defense of a Pony Express office from a loan shark…into a single-handed gunfight against a massive gang—much to Hickok’s chagrin) or, sometimes, specifically for a political agenda (painting Jesse James as a “modern Robin Hood” because of his pro-Confederate “Lost Cause” antics).

WHY IT’S A GREAT FILM:

Winner of four Academy Awards—Best Editing, Best Supporting Actor, Best Director…and the Oscar itself, Best Picture. Naturally, a film winning the latter two in particular deserves a look, at least. (Mind you, not every Best-Picture-winner truly deserves the title of “greatness”—Crash perhaps being the most notorious example…. But still.)

More than that, for all the unintentional after-effects on the Western genre that happened long after…Eastwood’s classic did have a vital purpose, for which “oater” fans should all be very grateful.

“DECONSTRUCTION” IN A NUTSHELL:

Unforgiven is the great deconstruction of the Western. That’s been said a lot—and most people don’t really know what it means. Bear with me:

Perhaps the best definition for “deconstruction” comes from TV Tropes. That excellent website’s very valuable for anyone wanting to study the various aspects of storytelling in general—film, television, books, comics, video games, etc. At any rate, the analogy TV Tropes gives for “deconstruction”—and “reconstruction”—runs like this:

Let’s imagine the genre (or whatever) is like a car. It’s run well for many years and done its job faithfully…but now, it’s got some problems. It’s not as reliable as it used to be—maybe it doesn’t start right, or its mileage is off. You don’t know what the problem is—everything looks the same as before. So what do you do?

Well, in order to figure it out, you take it to the shop, and you (well, the mechanic—but whatever) take out, examine, and put to the test any potential trouble spots—anything that could be holding the car back.

That’s “deconstruction”: When someone takes a hard look at the whatever-it-is, examining it to figure out what doesn’t hold up. In the case of storytelling, that tends to involve the question: “In real life, how would this genre convention we’ve always taken for granted hold up?”

One of my favorite examples is Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Basically, DS9 said: “Congratulations, Kirk/Picard/Sisko, you’ve initiated cultural change and reform. Now…what are the consequences of that?”

Once all the trouble spots are identified, they can then, afterwards, be fixed—and the car/genre/whatever can be restored to its former glory, “delivering the goods” in a fresh-feeling way, for a new generation. That’s what we call reconstruction.

But that’s for another time.

AFTER “HAPPILY EVER AFTER”:

Congratulations, legendary gunslinger. You’ve rode through the West for however many years, selling your gun for whatever causes. You may or may not have ridden on various sides of the law. But at any rate, you’ve met That One Woman, who opens your mind and your heart—and you find a sort of redemption. Maybe she inspires you to save the day against some bad guys. But regardless, when it’s all said and done, you decide to hang up your guns, and settle down with her…starting a new life.

It’s one of the oldest stories in the genre—all the way back to the first “big”, “serious” Western, Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian.

So…what happens next?

When John Wayne and Claire Trevor go off in the end of Stagecoach to that ranch he’s bought in Mexico…have you ever wondered how it all turns out? The way that typical story goes, we’re pretty much meant to assume that our gunslinger and his love will succeed in their new life—and they’ll live happily ever after.

As Yoda would put it: “So certain, are you?”

Look, if a man’s lived his whole life as a hardened killer—even if he’s been lawful and honorable about it—what makes us all assume that he can just flick a switch, run a ranch, and maybe raise a family? You’re asking him to leave the life he’s known, and start all over. What makes you so certain he can do that?

Yes, sometimes he can. But not always.

“I AIN’T LIKE THAT ANYMORE”:

That’s what William Munny keeps saying, throughout the movie—over and over and over, so often you really get the idea the person he’s trying his hardest to convince…is himself.

At any rate, he’s the hardened gunslinger who settled down with the love of his life—and when we meet him, you really get the idea that she was the one holding the ranch together. Now, she’s dead. And we see pigs dragging poor Munny around through the mud. He ain’t that good a homesteader.

But what about his old life? That’s another “oldest story in the book”—a veteran gunfighter who has hung up his guns is now called upon to take ‘em up one last time, to stand for what’s right.

So how does that hold up?

Well…for one, it’s been way too long since he’s hung them up. In a scene clearly meant to contrast a moment at the beginning of The Outlaw Josey Wales, Munny sets up some targets to shoot—and fails, until he gets a scattergun and rifle. But no luck with the old six-shooter.

He even struggles to get back on his horse.

The whole point is: If a man like that really put his old life behind him, completely—you can be sure of two things. One, it’s going to be a challenge to start a whole new life. Two, it’s going to be a real challenge to use all those forgotten muscles, if you’re that long out of practice.

Especially if that conscience is tormenting you about it.

THE TOLL OF KILLING:

As Little Bill explains to dime novelist Beauchamp at one point, gunning someone down isn’t the easiest thing in the world. And as we see in the film, that’s especially the case if 1) you haven’t done it before, or 2) you’re traumatized over the killings you’ve done before.

And so, when the first killing actually happens in the film, the victim—one of the cowboys the prostitutes put the hit on—gets shot in the gut, reduced to bleeding to death, calling out for water. Will and Ned, shaken by this, allow for the cowboy’s friends to bring it to him.

It isn’t the typical Western death—quick and easy. It’s slow, painful, and hard to listen to as the cowboy begs for some kind of help. (It’s made even worse when you remember that that cowboy wasn’t the one who attacked the girl—in fact, he was the one who tried his best to make amends for what happened.)

Schofield is notably frustrated at the unwillingness of Will and Ned to finish him off…but he comes to face his own trauma, upon shooting the last of the targets (the truly “guilty” one)—confessing to Will afterwards that it was the first time he’s ever killed a man.

The life of a gunfighter, even if you’re great at it, comes at a cost—one way or another. And in the case of poor Ned, it costs him his life—and not an “honorable” death in a blaze of glory. He’s tortured to death by Little Bill. And news of this causes something to snap in Will’s mind—his rage (and maybe a shot of whiskey to cool his head) motivating him to embrace his old “edge”.

William Munny’s back.

“WHEN THE LEGEND BECOMES FACT…”

One of the big issues of the film involves the question of “Legends of the West”. One of the central characters thematically, as it turns out, is W.W. Beauchamp—the dime novelist who initially follows along English Bob. Bob’s a “legend”—and he seems eager to use that to get away with goading people over the recently-shot President Garfield, and how no one would dare assassinate a monarch like that…or something.

He actually is a great shot—showing his skill early on, in a bird-shooting contest while on a train. It’s just that the stories about him—like those written down by Beauchamp—are a bit…flowery. And clearly written to make him look like a noble hero.

Well, Little Bill—for all his faults—will have none of it, laying out for Beauchamp the truth behind all that:

Meanwhile, we also see some in-universe deconstruction of the respective legends of Will Munny and The Schofield Kid—the latter having made up the “legend” himself. As previously noted, Schofield even admits he hasn’t killed before.

As for Munny, we hear endless references to his reputation as a super-cold-blooded “killer of women and children”. It’s never spelled out, but one really gets the idea that it’s all exaggerated—either by his enemies to smear him as “evil”, or by himself to frighten would-be enemies into giving up rather than face him.

Munny isn’t sure, either way. He drank too much in those days to remember the details. Or so he says.

At any rate, he pretty much embraces his “stone-cold legend” image for the final gunfight—again, to terrify most of Little Bill’s goons into leaving before the shooting starts. He succeeds.

And when the fight does break out…he’s every bit as skilled as we could ever want.

Good enough.

THE PROBLEM OF QUICK-SHOOTING:

This is perhaps my favorite of the “deconstructive” elements of the film. After tearing English Bob’s “legendary” saloon gunfight to shreds, Little Bill lays out for Beauchamp exactly why “shooting on the draw” is not true-to-life—at all. Drawing quickly itself is great (buying you time to aim sooner)…but shooting fast? That’s another story:

I mostly like this because Little Bill does allow for drawing quickly—and let’s be honest: that quick-draw he demonstrates to Beauchamp’s pretty quick. Just not ridiculously, Spaghetti-Western quick.

CLINT EASTWOOD:

I was getting to this one, folks—thanks for waiting!

Clint Eastwood—in addition to being one of the greatest movie stars of all time, a multiple Oscar-winning director (see those “golden guardians” in his sort-of cameo in Rango). And to many, this one’s his masterpiece—on both sides of the camera.

His portrayal of Will Munny relies a lot on his past roles for effectiveness, to be honest. When we see him struggling so much, throughout the film…let me tell you, it’s so hard to watch! This is Clint Eastwood, for goodness sake—The King Of All Men, the ultimate bad—s, Dirty Harry, The Man With No Name, Josey Wales…

And lo and behold, he’s struggling to get on his horse—let alone shoot a gun, or even gets some pigs under control! And when Little Bill and his goons beat the tar out of him at the midpoint of the film, we can only cry out, “HOW IS THIS POSSIBLE?!?”

Well, that’s part of the point. Clint himself has said he got ahold of the script years before. He then sat on it, until he was old enough to play Munny. As far as he was concerned, it had to be him—and no one else. It had to be Clint we saw going through all that, to achieve the maximum effect. We had to accept without question that Will Munny used to be a master gunslinger, so that we could react the way we’re “supposed” to.

It’s painful to watch him humiliated so deeply. We beg for the film to give him his “mojo” back. We want him to gun down those cowboys, and we want him to stand up to Little Bill.

And finally he does. And yet…

“DESERVE’S GOT NOTHIN’ TO DO WITH IT”:

Will Munny hears tell of Ned getting beaten to death by Little Bill—and like that, he gets his edge back…executing his steely-eyed, cool-headed, cold-blooded revenge on Little Bill, and the bartender-pimp, and the others who dared to stand in his way.

We cheer him on…but at the same time, we wonder if we’re supposed to. Clint shoots the sequence in the dead of night—thunder and rain pounding outside. Undertones and overtones of darkness. In the back of our minds, amid cheering his restoration…we wonder, “Restoration to what?”

After all…this whole time, he’s been insisting that he doesn’t want to go back to being what he was. After all, “I ain’t like that, no more.” His love for Claudia thawed his heart—and he doesn’t want to be a “killer” again.

In getting his “edge” back as a master gunslinger…has he turned his back on that redemption?

Of course, there’s a bit of reassurance, as he makes it clear to his enemies why he’s doing it (“Well, he should’ve armed himself…he’s gonna decorate his saloon with my friend.”). And when it’s all said and done, he warns the town to “bury Ned right” and to treat the prostitutes with respect—or he’ll bring down horror on them all. Again, he’s embracing his dark legend—but for an arguably noble cause we feel for him about.

Besides, the epilogue notes that he and his kids went on to use the reward money to start a successful trade business.

Maybe there’s a new life for a gunslinger, after all.

THE REST OF THE CAST:

Gene Hackman’s Oscar-winning turn as the villainous “sheriff” Little Bill—conveying a slimy sort of charm with simmering, barely-stable, frankly-terrifying menace. As I noted elsewhere, this performance is proof that he couldhave, were he so directed, played Lex Luthor seriously.

The magnificent Morgan Freeman as Ned—at once more stable and secure in his post-gunslinger life and, ultimately, less capable of getting back into the game. Maybe the two traits go together, the film implies…and that makes Ned’s fate all the more tragic.

Richard Harris has a nice turn as English Bob—flamboyant, and later convincingly humiliated. And if you pay attention, he drops his “posh” Queen’s English accent after said humiliation, for a “commoner’s” Cockney. Even Bob’s voice was a façade.

Saul Rubinek plays W.W. Beauchamp (and if you listen carefully, Little Bill makes “Mr. Beauchamp” sound like…something else)—the writer with a boyish enthusiasm, eager to write about living legends of the West. He starts off with English Bob—until Bill tears that legend apart. He remains with Little Bill to get some good pointers about (presumably) accurate depictions of “experienced gunfighters” and their methodology. (Of course, as Munny later points out to him, you often have to rely on luck when it comes to the “proper order”, because you often don’t knowwho the “best shots” are!) And then, when Will Munny proves sufficient truth to a legend of his own, Beauchamp’s elated at the chance to interview The Real Deal—leading to the dark humor of Munny frankly unsure of what to make of this guy’s enthusiasm after watching the gunslinger just kill some people!

THE THEME:

Clint Eastwood is a man of many talents. And wouldn’t you know it…the main theme of Unforgiven, called “Claudia’s Theme”, was composed by Dirty Harry himself. Soft, mellow, sad…tragic, somehow—especially considering how it’s linked by name to Will’s late wife, the woman who got him to hang up his guns and change.

Even when he “goes back”, her influence is still felt…as we hear the theme once more, amid the text of the epilogue.

Sadly, the mellow, understated music of Unforgiven is another example of how the film inadvertently “inspired” an unfortunate trend (again, a decade or so later) in contemporary Westerns. As I complained about in my Magnificent Seven article, even James Horner’s score for the remake isn’t nearly as memorable as the original’s. And that’s one of the superior examples of Western scores, nowadays. As a rule: toned-down…functional, but if the score ismemorable at all, it’s…“moody”. And often centered on a slowly-played acoustic guitar. Rarely anything resembling Bernstein—or even Morricone.

Ironic, because I defy anyone to tell me “Claudia’s Theme” isn’t memorable. Sometimes, it’s enough to bring a tear to one’s eye.

As I said…I don’t blame Clint.

BY THE WAY…

Ironically, some of the deconstruction invoked by Unforgiven seems to have been anticipated by the Western genre’s earlier reconstruction—Lawrence Kasden’s Silverado, the film that kick-started the genre’s renaissance in 1985. Namely…remember that great scene above, where Little Bill lays out the foolishness of shooting on the draw—and explains that it’s better to take your time and mind your aim? Well…wind the clocks back a full seven years to Silverado, where Kevin Kline stands on the street calmly loading his (cheaply-bought and all-banged-up) gun and minding his aim, while his opponent’s riding hard and firing quickly….

“William Munny” may or may not be a spin on William H. Bonney—“Billy the Kid”. Like Will, Billy found himself the subject of a probably exaggerated legend (that he killed “one man for every year of his life”—totaling 21). Unlike Munny, Billy either died at 21 or faked his death to enjoy retirement free of pursuit from the law.

English Bob being called “The Duke of Death” (or “The Duck”, courtesy of Little Bill) is, of course, a “kind-of, sort-of” reference to John Wayne, “The Duke”. Of course, Bob’s as different from Wayne as night and day. The Duke, remember, had a rule to never go around acting like you’re looking for a fight. But just like Wayne only said “Pilgrim” in a couple of films, sometimes we remember things differently than they really were….

There was actually a classical Western called The Unforgiven (1960), starring Burt Lancaster, Audrey Hepburn, and Audie Murphy. Not the same story. At all.

Buy or rent this classic here. And stay film-friendly, my friends.

WHAT’S NOT ON THE LIST:

Tombstone (1993)—another film I’d have loved, loved, loved to write an article about. It’s one of the truly great films of the Western genre’s brief renaissance. And the great Ben Shapiro eagerly included it on his list.

Naturally, I don’t tend to disagree with Ben lightly, especially on pop culture he does like. (As a rule, he’s right-on when liking something, and problematic when he doesn’t—deeming J.J. Abrams, Quentin Tarantino, and even Alfred Hitchcock “overrated”. But then, All Film Is Subjective. I sort-of agree with him on Frozen, though.)

Alas, I can’t agree with him on this. His take on Tombstone’s based on the “Good-vs.-Evil theme = Conservative” argument—and in the intro to this series, I explain the problem with that. Remember: the Left absolutely believes in clear-cut Good and Evil—they happen to think we’re evil, and they’re good.

Even Tombstone’s pro-Law-&-Order theme doesn’t quite justify its inclusion. It might have…if only the film had focused on a Conservative take on the subject. Alas, when Virgil Earp (the magnificent Sam Elliot) becomes Town Marshall, he sets to work imposing…a gun ban.

Yep.

Wyatt Earp (the mighty Kurt Russell), to his credit, balks at this—but it’s portrayed as another example of his reluctance to get involved in cleaning up Tombstone. Sadly, unlike Unforgiven, this Western—like too many others—falls prey to the trope of showing a town-wide ban on guns as a good thing—“necessary” to maintaining…law and order.

I love this movie, though—everything from its pitch-perfect cast (Val Kilmer, anyone?), to its dramatic set pieces, to Bruce Broughton’s epic score. It’s also one of the more historically accurate takes on the Wyatt Earp story.

It just isn’t particularly Conservative. Conservative-friendly, perhaps. But not Conservative.

***

Eric M. Blake Bio:

Eric M. Blake is a recent graduate of the University of South Florida, with a Bachelor’s in Political Science and a Master’s in Film Studies. As that implies, he is very passionate about political theory and filmmaking–and the connections between the two. Inspired by Andrew Breitbart’s axiom that “Politics is downstream from culture”, he is deeply fascinated by the great influence that popular culture has on public opinion, and is a firm believer in the power of storytelling. He proudly owns his second copy of Ben Shapiro’s Primetime Propaganda… his first copy having been worn out though intense re-reading.

Eric was raised by Conservative Christian parents, but first became especially passionate about politics in high school, through reading up on economic theory. He also first read The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged around this time, for the ARI’s essay contests. He now owns a great deal of Ayn Rand’s work. Also included in his library are the collected works of Rush Limbaugh, Mark Levin, Ann Coulter, etc.

Eric is no stranger to writing commentary, as the writer of the Conservative Considerations column on CampCampaign.com, and as a film critic and commentator on FlickRev.com. He has also carried on the Conservative tradition of talk radio commentary, as the host of “Avengers of America” for the USF student radio station, Bulls Radio. In the meantime, he is practicing what he preaches: Striving to enter the professional realm of Hollywood, he has already written and directed short films for the Campus MovieFest, which can be found on his YouTube channel, Hard Boiled Entertainment.

****

Film poster via apotpourriofvestiges.com

Comments

Leave a Reply