Editor’s Introduction:

Dear Fred, Alec, Jon, and Chris,

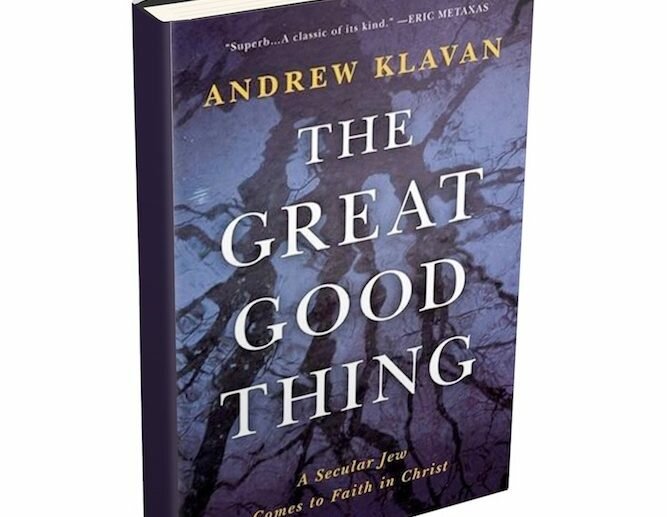

I’d like to thank all of you for agreeing to participate in this symposium discussing the ideas of Andrew Klavan’s extraordinary memoir The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith In Christ. From the outset, I must admit a motivation behind organizing this group analysis: my own failure to write a review in a timely fashion about this, my favorite book of 2016.

I wanted to write about how the book offers so many layers of depth and intellectual challenges; and how it inspires at the personal level and engages the emotions. This is not merely a book about one man’s conversion — it’s about his journeys through life and the mental, psychological, and spiritual tools he developed along the way.

And so I think the most fruitful way to explore Klavan’s book and its myriad themes and ideas, is through this discussion format, where each Liberty Island contributor can highlight aspects that spoke most to him and then we can see what connections we can draw between them. This discussion has been edited into three sections. In Section I each writer offers their initial thoughts on an aspect of the book which moved them. In Section II they have the opportunity to engage in dialogue about each other’s points. And in Section III each concludes with final take-away points on the lessons they draw from Klavan’s life and work.

We’ll start the symposium with the contribution of Fred Tribuzzo, author of the upcoming Liberty Island thriller novel Pulse of the Goddess…

– David

Section I: First Thoughts

Finding God in the Blood and Guts of Birth and the Big Bang

By Fred Tribuzzo

In the years following Christ’s ministry on earth, Roman generals would witness the jaw-dropping scene of Christians comforting dying soldiers with food, water, and companionship. In the pagan world of antiquity, undesirable children up to the age of two were often left in the forest to be devoured by wild animals before the early followers of Christ started rescuing the innocents. And, in the Gospel of John, Christ quietly reminds a mob of their own sins as they’re ready to stone a woman to death for hers. This shift toward universal charity, welcoming the stranger, the sinner, and the less-than-perfect, becomes the heart of the Church. A new fight is born against human prejudice and all forms of slavery through love.

In pursuing the writer’s life, Andrew Klavan in his teens is drawn to the New Testament. He discovers that Western Civilization is powered by the Bible, especially the Gospels. Klavan boldly states that Christ illuminates the center of our Greco-Roman, Judeo-Christian heritage in The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ. It is the Son of Man who calls sacred the high and the low, the healthy child and the deformed one, the saint and the adulteress, the stranger dying on the battlefield.

Respect for life, love of that very life, across all people and all time, glues Klavan to Christianity even though he lacks belief in God as a young man, stating in his memoir: “Faith is the death of thought.” In his twenties, Klavan fears the loss of the intellectual life, the death of a writing project, neutralized by the numbing restrictions of faith. After all, it’s the Sixties, the rise of the New Left, and postmodernism actively seducing millions of baby boomers with the gift of a morally relative universe: If it feels even relatively good, do it.

Klavan says, “Individual freedom, equality before the law, and tolerance for conflicting opinions,” were once academia’s mission in fostering The Good Life, the Great Conversation. These bedrock beliefs have been derailed by the Left’s vow to deconstruct cherished ideas and demonstrate the fantasy of absolute truths, especially those of the the Western persuasion found in our Declaration of Independence. Andrew Klavan rightly concludes in Chapter Eight:

“To abandon those basic principles seemed false to something equally basic within me. It seemed an act of violence against my idea of what a human being was. I was torn between the intellectual fashion of the day and my own deepest convictions.”

Klavan argues that along with the “political wisdom” distilled into the U.S. Constitution, Christianity has also inspired the flourishing of the arts and sciences. He talks of Shakespeare and other greats, saying we just have a lot more of everything— more genius—Cervantes, Bach, Mozart and Dickens, and more science from cathedral building of the eleventh century to Newton and later, quantum mechanics. Saint Augustine believed that over time new sciences, “new arts” would continue to arise.

In the “blood and guts of birth,” Klavan witnesses the arrival of his first child and the floodgates of love thrown open wide for his wife and daughter. In an instant Klavan understands three lives have merged into one flesh, a “new art.” The experience is a whitewater rafting event that rushes the author headlong into the cosmos where love eternal ignites the Big Bang.

The End

Part 2 coming next Thurday…

Comments

1

Leave a Reply

What a teaser!

I purchased a copy on Amazon yesterday and can’t wait to read it and share with my parents, both baby boomers who were raised with little to no religion and few barriers to freedoms afforded the young and willing during the 60’s.