Young Christopher worshiped a superhero. There was no help for it; the spirit of the man was in the very air he breathed in Boone’s Lick, Missouri – the final stop for that famous family. Christopher’s own family lived on land purchased from the Boones and had intermarried with them. He would sit wide-eyed by the fire as the men told stories, sometimes repeatedly, of the exploits of Daniel Boone.

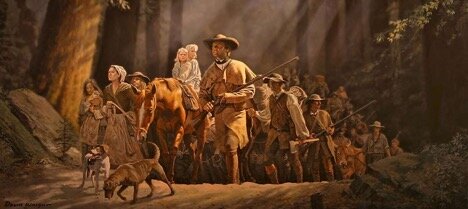

He was told how Dan’l got his first rifle at the age of twelve; and how he promptly shot a panther through the heart in mid-air as it pounced, while his young companions ran for their lives. Christopher knew that Daniel Boone was the first to lead the pioneers on the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland gap to the Ken Tuc Ky – the “dark bloody ground” where tribes from all points of the compass met to settle their differences in battle. He thought how foolish it was for that Shawnee war party to kidnap those Boonesborough girls foraging outside the settlement. Did they not know one of them was Jemima Boone? It took but two days for her father and some friends to track them down, surprise them as they ate – kill some, scatter the rest, and bring Jemima and the other two girls home safe and unharmed.

When British General “Hair-buying” Hamilton hired the Shawnee under Chief Blackfish to attack the Kentucky settlements and lay siege to Boonesborough, Daniel was captured with a party of men trying to get salt to preserve what was left of their food from the springs on the Licking River, and brought back to the Shawnee village. He was forced to run the gauntlet, and did so well he was adopted by Blackfish himself, and given the name Sheltowee: “Big Turtle.” Yet hearing that the Shawnee planned to return to Boonesborough once again, surprise it and force its surrender, Boone escaped. He rode part of the 160 miles back until his horse played out, then ran most of the rest of the way, arriving in Boonesborough just ahead of the Shawnee to help prepare its defense. A ten day siege ensued, until at last, with heaven-sent rains putting out the fires launched into the fort, and word of North Carolina militia on its way, Blackfish retired.

Christopher also never forgot how, after all that, and after having lost two sons in the struggle against the Shawnee, Daniel Boone refused to participate in, or even cooperate with, a subsequent campaign of annihilation against Blackfish and his people. In his old age, Daniel Boone often preferred the company of his old Shawnee adversaries for hunting trips and general socializing.

Christopher only wished to be half the man his hero was. After his father died, his mother remarried and apprenticed him to a saddler in Franklin, Missouri, at the eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail. He knew he’d never be anything like his hero spending his life making saddles. Seeing and hearing from the trappers and traders coming in from the west, He ran away with a caravan of them, tending their cattle all the way to Taos, in what is now New Mexico. He settled in with a trapper named Mathew Kinkead, who finally began to teach Christopher the skills he craved – the skills of his hero. He even picked up some Spanish and Indian languages along his way. It was not long before he was accompanying famed mountain men like Jim Bridger and Bill Williams on their treks.

When he was nineteen Christopher joined Ewing Young’s trapping expedition, which was attacked by Apaches along the Gila River – Christopher’s first taste of battle. They went on to explore Spanish California; from Sacramento to Los Angeles. For ten years Christopher hunted and trapped all along the central Rockies. His chief adversaries were the Blackfeet; his encounters with them ran from minor skirmishes to pitched battles.

Returning from some family affairs aboard a steamboat on the Missouri, Christopher encountered Major John Charles Fremont – soon to become known as the Pathfinder. Just a few conversations and Fremont was convinced he needed to hire Christopher as a guide for his expedition to map and explore the Oregon Trail to South Pass, Wyoming. In their second expedition, they reached the Columbia River in Oregon. There were side trips to Salt Lake in Utah, and of course, to Christopher’s beloved California.

The third expedition had a more clandestine purpose – President Polk wanted California. Under the guise of an exploratory mission, Christopher led Fremont into California to gain intelligence on the attitude, attributes and capabilities of the American settlers there. Fremont encouraged and provided force recon for what became known as the Bear Flag Revolt; which, combined with the results of Polk’s Mexican War, brought California and the Southwest into the American fold.

It was in the Mexican War that Christopher performed his most incredible feat. Having been sent by Fremont back to Washington to deliver reports, Christopher came upon Gen. Stephen Kearny, who soon found himself in dire straits – vastly outnumbered and surrounded by the Mexican Army at the village of San Pasqual. Christopher, a navy lieutenant and an Indian scout, slipped past the Mexican lines, wearing little or nothing upon their feet so as not to make noise or leave boot tracks. They hiked 25 miles through the desert – over prickly pears and rocks – all the way to San Diego, where they arrived half-dead from thirst. A few days later Kearny had given up hope and was about to launch an almost suicidal breakout charge, when the Mexicans before him scattered. Two-hundred United States Marines from San Diego had arrived – led back by Christopher.

During his long career Christopher did battle with Indians from various tribes; and as typical for the day, neither side observed European rules of war or etiquette. Yet two of his three marriages were to native women (the third was a Mexican) and Christopher would become known later in life as an advocate for Indian rights; and like his hero, often preferring their company.

If the settlement and acquisition of the American West – the culmination of the dream of a nation “from sea to shining sea” – can be attributed to just one man, it would be Christopher “Kit” Carson.

American history is a pantheon of heroes that make Homer and Virgil seem palsied. So pick one, or two, or three, and set them as stars by which to navigate – and you may find yourself going where no one thought you could.

*****

Post Script: The author spent a recent Saturday binge-watching a childhood favorite – the old DANIEL BOONE TV show from the 1960s:

It was full of cornpone and historical inaccuracies, but its themes were often unabashedly patriotic and kind towards religion. In one episode Boone & Co. save the Liberty Bell from falling into British hands as it is brought out of Philadelphia after its fall. In another, Boone escorts a vital cannon made from donated metals through the wilderness to assist George Rogers Clark in his campaign against Fort Vincennes. Boone’s young son Israel is depicted learning his lessons for school – his primer is the King James Bible. A host of colorful guest characters of every color and walks of life enter the stories – often conflicted in their values and in need of redemption – until the trail blazer Daniel Boone sets them on the right path with his uniquely American wisdom. Ask yourself, dear reader: What are our children watching or reading today that will give them heroes by which to set their navigation?

Comments

Leave a Reply